Michael Alexander investigates why a connection between First World War shrapnel victims and modern day traumatised war veterans has inspired an American writer to change lives for the better – but has prompted him to warn that much more needs to be done.

Twenty-two years past August, award-winning American author and screenwriter Don Snyder turned on the radio at home in Maine and was shocked to learn there had been a Republican terrorist car bombing in Omagh, Northern Ireland.

Just a year earlier in 1997, Don had travelled around Ireland with his wife and four children and, having found Omagh to be “the most peaceful place on Earth”, it seemed “impossible” to him that an atrocity causing the death of 29 and injuries to 300 could have happened there.

Feeling a deep connection, and with ideas for a novel already swirling around inside his head, Don jumped on a plane from Boston to Dublin, and within 24 hours of the blast found himself walking the streets of Omagh which were still littered with broken glass and stained with blood.

He spoke to many eyewitnesses and even attended 13 funerals.

It was when he returned to Omagh a year later to further research his novel Night Crossing, however, that a deep interest in blast victims and traumatised survivors of conflict was born.

“I was standing in the pub one night a year after the bombing, and I was talking with a guy three or four seats away from me when I realised there was something perplexing about him – his expression never changed,” recalls Don.

“It was after he left, the bartender told me he was one of the people in the town injured by the blast and he had chosen a mask to conceal his horrible wounds rather than plastic surgery.”

Don remained haunted by the image of the man “hiding” behind a mask in the Omagh pub that night in the late 1990s.

It wasn’t until a 30th anniversary wedding visit to London with his wife in 2014, however, that Don had the “powerful” realisation that war victims from the past were intrinsically linked to war victims of the present.

Lost in silent reflection outside the Tower of London, the estimated 40 million military and civilian casualties of the First World War was thought provoking enough while he and his wife gazed at the Blood Swept Lands And Seas Of Red poppy installation by ceramic artist Paul Cummins to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War.

It’s estimated that between 15 million and 22 million people died on all sides in the 1914-1918 conflict.

But while Cenotaphs specifically remember the dead, the more he read up on the subject, the more he was affected by the post-war plight of the 23 million war wounded – specifically soldiers who often suffered terrible life changing physical and psychological injuries.

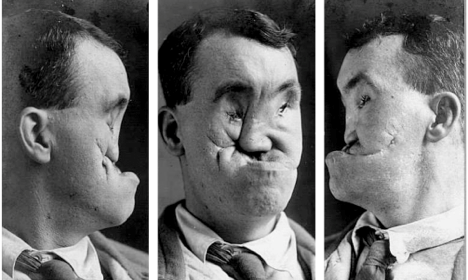

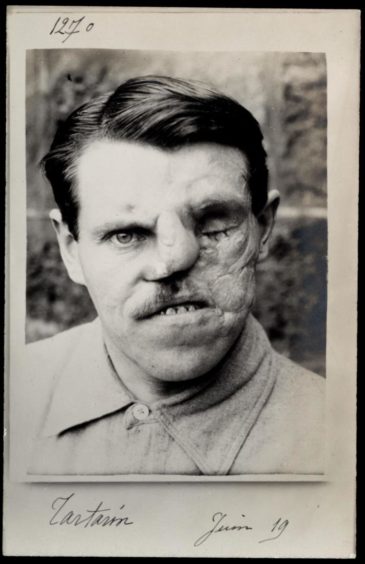

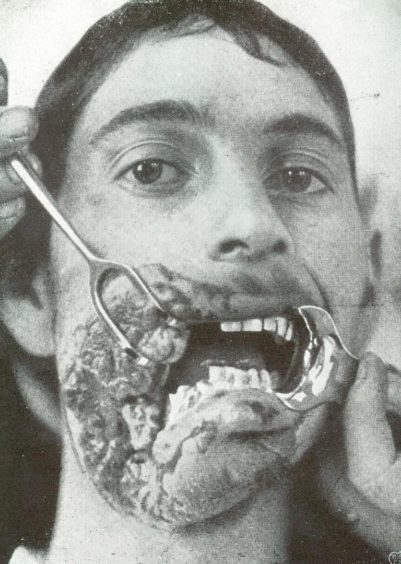

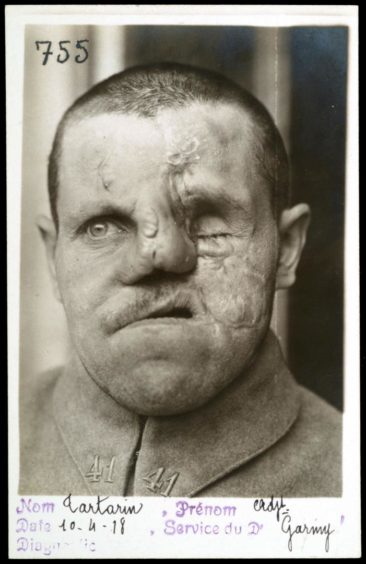

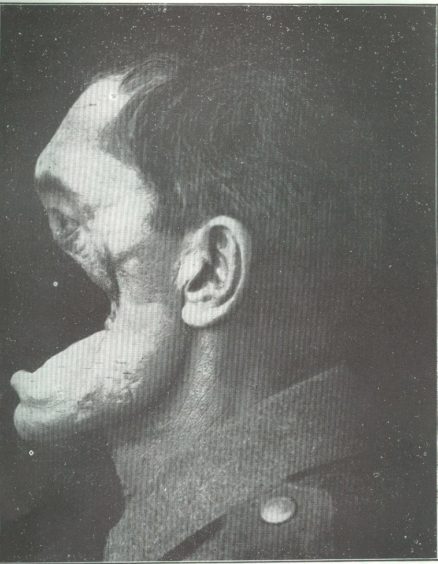

The realities of what machine gun fire and shrapnel did to the human body was spelled out when he read an extract from the medical journal of a First World War battlefield surgeon.

The quote said: “The jagged fragment of a bursting shell will shear off an ear, a nose or a part of a jaw leaving the victim a permanent figure of revulsion to others and a grievous burden to himself.

“It is not to be wondered at when such men become victims of despondency, of melancholy, leading in some cases even to suicide.

“What is particularly haunting for me now are the ’healed’ faces that I see in this hospital – the men for whom surgery is finished and no more can be done.”

The photographs of these mutilated First World War soldiers certainly spoke for themselves.

So, in 2015, having never forgotten his experiences in Omagh, Don went to Belfast to write a screenplay about these World War One soldiers who lost their faces before ending up in a place they called the Tin Nose Shop.

It was his way of telling the world about these ‘forgotten’ heroes of the so-called ‘Great War’.

It focussed on the horrific injuries many of these soldiers had to live with and how they would often “hide” away from society after being fitted with crude, tin masks. Many were driven to suicide.

But at a time in his life when Don had begun doubting whether writing was truly enough to make a positive difference in the world – and as he learned more about modern day soldiers returning from wars in the Middle East with severe injuries and PTSD including those taking their own lives – he began to wonder whether there was anything else more tangible he could do to make the world a better place.

Around this time, Don had been talking to actor Gary Sinise – who starred in his Emmy-nominated 2003 film Fallen Angel.

Gary had set up a centre for disabled soldiers near Don’s home in Maine.

Gary’s motto was: “We can never do enough for these soldiers but we can always do something more”.

Don says: “As a writer you can always take refuge in this illusion that you are doing enough because you are bringing truth and beauty to the world. But Gary’s words were rattling around in my head and I wanted to do more.”

In 2008 and 2010, Don had sought a new challenge spending time in St Andrews working as a caddie.

He was in awe at the camaraderie of caddies.

The “mission oriented” band of brothers’ mentality, often in the face of hardship, reminded him of the military.

While he’d never served himself, he was reminded of his Second World War veteran father Richard who, back in 1950, had been left bereft by the death of his 19-year-old wife Peggy just 16 days after giving birth to Don and his twin brother.

Don’s father used to sleep on Peggy’s grave, and was only brought back from the brink of deep despair by his Second World War veteran colleagues who supported him and ultimately saved his life.

That’s when Don had the brainwave: Could he do something through golf to stop modern day soldiers from killing themselves?

After conversations and funding from Don’s old golfing friend Charlie Woodworth, Don launched the world’s first Caddie School for Soldiers at the Duke’s Course outside St Andrews in February 2019.

He was supported by the Kohler family who own the Old Course Hotel and the Duke’s, contacts he’d made during his time caddying in St Andrews, and by Richard McDermott who funded the second session in February 2020.

The first two sessions were a great success.

To him, the veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq looked like “ghosts” when he first met them. Some had visible wounds. Others were “hiding” them.

So to see them “rise up” from that through a month of camaraderie and purpose on the golf course was remarkable.

The healing power of a purposeful four hours in the fresh air with a stranger allowed them to step away from their own “darkness” and step into someone else’s life.

Don remains hopeful for the future with ambitions to set up a permanent Caddie School for Soldiers base in Scotland – preferably in the St Andrews or Cupar areas – if the right premises can be found.

He’s recently worked up his original Tin Nose Shop screenplay into a novel called Lies About Love, and, ahead of its release in the UK, is working with his agents to source interest in turning it into a “Netflix or Amazon” type TV series which he hopes could fund a permanent Soldiers’ Caddie School in Scotland.

However, with the Covid-19 lockdowns having already forced the cancellation of a Caddie School event at Whistling Straits, Wisconsin, in October and a Covid question mark now hanging over the third Caddie School for Soldiers session at St Andrews in February, recent events have left Don feeling increasingly anxious that the physical and mental health needs of ex-soldiers today and the needs of ex-soldiers after the First and Second World Wars remain as connected – and urgent – as ever.

Two days before this interview, the chairman of Don’s Caddie School board sent him footage of a memorial service in Georgia where another depressed US soldier had dramatically taken his own life. Veterans had gathered to honour their fallen colleague.

“My immediate reaction to that was to write to the Kohlers and say ‘we just have to do more’,” says Don.

“There’s just too many of these soldiers out there who are hurting. The pain they are enduring is unimaginable.

“We are supposed to be in Wisconsin right now. But because of Covid I had to disappoint six soldiers.

“We’ve set that session up for May hoping we’ll be out from underneath this thing – but this remains to be seen, as does the Scotland thing for February. It’s tough.”

Determined to “step up a gear” with his plans for a permanent Scottish base, Don says he’s been writing weekly to North East Fife MSP Willie Rennie and Angus MSP/Veterans Minister Graeme Dey to give them updates on who’s supposed to be coming to St Andrews in February 2021 and to ask about the likelihood of this being possible.

The veterans have offered to come 14 days early to quarantine if they are allowed to live and work as a ‘bubble’.

However, while understanding the difficulties of predicting Covid restrictions, Don says the relative lack of clarity and guidance has been frustrating.

With a December 15 go/no go date in mind, he worries what the mental health impact on ‘his’ fragile soldiers might be if the event has to be called off.

Veterans, who enjoyed “deeply meaningful” relationships at war with their fellow soldiers, talk to him about the “increasing shallowness” of society and feeling “alien”.

When Don recently asked a veteran what he meant by that, the veteran replied: “Well you’re the first person I’ve talked to for a long time who wasn’t staring at their phone!”

Don says: “My position on this from the beginning has been to take necessary precautions but carry on – don’t fold up, lay down and give up.

“We have to remember these soldiers I’m talking about – they’ve been living in this isolation for a long time either inside their minds or inside the world they are in. The world of darkness.

“But you can’t really measure the cost of calling off something like the February session.

“We don’t know what effect it will have on these soldiers.

“These soldiers that we are dealing with now have spent a lot of their lives since they got out of the military hiding – just as those World War One soldiers who lost their faces were hiding behind masks. There is a similarity there.

“But we have to try to do what we can I think. That’s where I am right now. I’m going to take the soldiers’ motto – ‘plan for the worst and hope for the best’.

“I know that we might have to call this off on December 15, but I know we’ve got a fighting chance which is all we can ask for.”

Don says he created the Caddie School to honour the First and Second World War soldiers – as well as this new generation who embrace the same qualities of service and sacrifice.

“They carry themselves with the same humble nobility,” he adds.

“Let us never forget they have all given so much for the rest of us. The least we can do is give something back.”

Politicians’ views

*Contacted by The Courier, North East Fife MSP Willie Rennie said when he met Don and his caddies last year he was “so impressed” by the work being done to give them new opportunities. It literally changed lives.

However, the Covid times we are in mean that, inevitably, there are considerable uncertainties.

“The delay to this year’s school is a powerful example of the impact of this virus which is not just on people who catch the it but those who are affected by the limitation on our freedoms that comes with the shutdown of society,” he said.

“This virus is so contagious so we need to be cautious but the first opportunity of getting the virus under control I hope we can open the door to the caddie school.”

A Scottish Government spokesperson said: “Suppressing the spread of coronavirus (COVID-19) remains the Scottish Government’s top priority and current restrictions have been introduced to protect the health of the public.

“We appreciate how difficult planning events can be, but given the rapidly changing nature of the virus it is simply not possible to predict at this stage what restrictions will be in place in the coming months.”