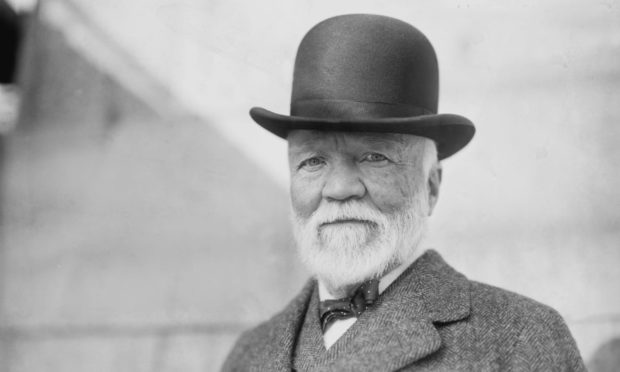

Andrew Carnegie rose from humble beginnings in Fife to become one of the richest men the world has ever seen.

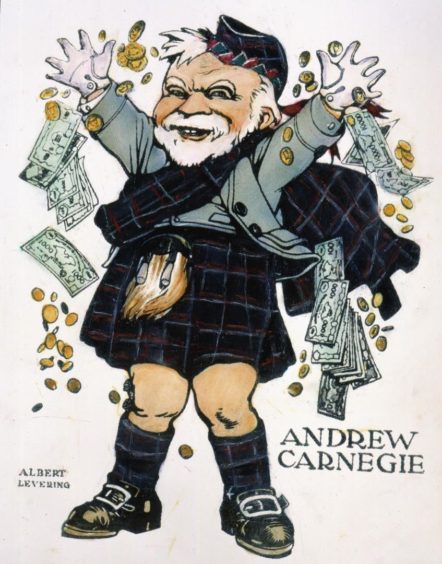

Carnegie was the Bill Gates of his time who is known as the father of modern philanthropy after giving away the bulk of his fortune.

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline on November 25 1835 in a small two-storey cottage at the junction of Priory Lane and Moodie Street which is now incorporated within the Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum.

He was educated at the Free School in Dunfermline, which had been a gift to the town by the philanthropist Adam Rolland of Gask.

Early years

His father was a handloom weaver, but by the 1800s this trade was in decline and the Carnegie family were struggling to make ends meet.

In May 1848 they sold their possessions, borrowed £20, and set sail for Pennsylvania where two of his mother’s sisters were already staying.

Carnegie’s migration to America would be his second journey outside Dunfermline – the first being an outing to Edinburgh to see Queen Victoria.

Carnegie started his working life aged 13 earning $1.20 a week as a bobbin-boy in a textile mill.

Ambitious and hard-working, he went on to hold a series of jobs and first moved to Hay’s bobbin factory where for $2 a week he tended the steam engine and fired the boiler.

Then in 1849 he was offered a job working as a telegraph messenger boy for the O’Reilly Telegraph Company, and, after teaching himself Morse code, was promoted to telegram operator.

Thomas Scott

Gillian Taylor, CEO of the Carnegie Dunfermline and Hero Fund Trusts, said this job brought him into contact with Thomas Scott who was the superintendent of the Pittsburgh division of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company.

He advanced rapidly under Mr Scott’s tutelage and by 1859 had succeeded Scott as divisional superintendent and was able to employ his own brother, Tom, as his personal assistant.

While in this position, he made profitable investments in a variety of businesses, including coal, iron and oil companies and a manufacturer of railroad sleeping cars.

Gillian said: “Through the railways, Andrew’s legendary career was launched.

“Andrew was an incredibly astute businessman who realised that America had a growing need for steel to make railroad tracks and bridges.

“So, he moved into steel production at just the right time for the boom in constructing skyscrapers.

“He became known as the ‘King of Steel’.”

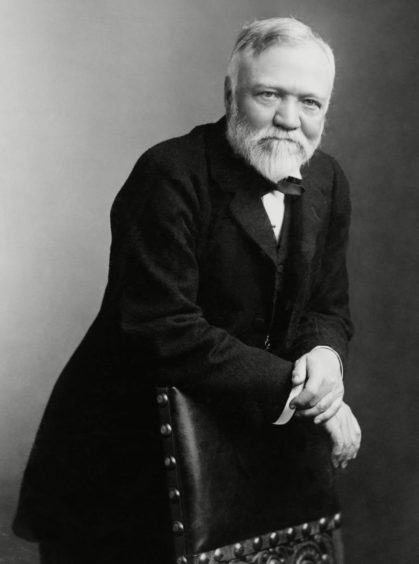

Rising profits

Steel poured from the furnaces of Pittsburgh and by the end of the 1890’s the Carnegie Steel Company was making almost half of the steel produced in America and was producing almost as much as the entire output of the British steel industry.

The annual profits kept rising and by 1900 the profits of the Carnegie Steel Company were 40 million dollars.

In 1901, aged 66, he sold the business to banker John Pierpont Morgan for $480m who merged Carnegie Steel with other businesses to form US Steel, which became the world’s first billion-dollar corporation.

Carnegie retired from business and devoted himself to full-time philanthropy.

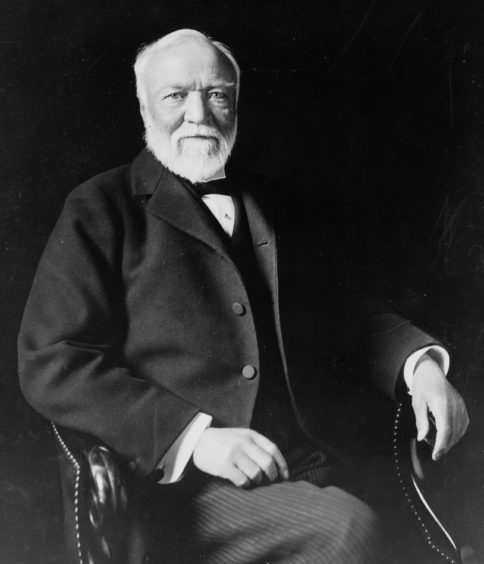

His legacy may have been very different had he not married Louise Whitfield, the daughter of a New York merchant, in 1887, who exerted a deep influence on her wealthy husband.

The couple honeymooned at Kilgraston House, Bridge of Earn, and thereafter every summer was spent in Scotland.

Highland home

Carnegie later bought Skibo Castle in the Highlands as their summer home following the birth of their only daughter, Margaret, in 1897.

The original cottage in which Carnegie was born, was bought by Louise for his 60th birthday and when the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust was set up in 1903, it came under the trust’s remit and eventually opened to visitors.

Carnegie visited the museum in 1908 – an occasion marked by his entry in the visitors’ book.

Gillian said: “Although Andrew’s formal education ended at the age of 13, when he left for America, his home provided a stimulating and literate background and he developed a great love of reading early in his life.

“It is, therefore, not surprising that one of his main contributions to society was the funding of free libraries, over 2,800 worldwide with around 660 in the UK.”

In 1889 he published the Gospel of Wealth, an article outlining the responsibility of the new upper class of self-made rich people to help the common man, stating millionaires were just “trustees for the poor”.

Firm belief

Gillian said a quote taken from the article speaks of his determination to ensure that libraries should be available to everyone: “If ever wealth came to me, it should be used to establish free libraries.”

She said he firmly believed in their educational and cultural importance and this stemmed from his own experience when, as a young working boy in Pittsburgh, he was given access to the private library of Colonel Tom Anderson.

“He never forgot the benefits he gained from this,” she said.

“Of all the trusts set up by Carnegie, however, the Hero Fund movement was the one closest to his heart.

“The first Hero Fund, the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission, was established in Pittsburgh in 1904 following a colliery disaster which claimed the lives of 181 men, including two who had entered the mine after the explosion in ill-fated rescue attempts.

“The Carnegie Hero Fund UK was founded in 1908 and covers the geographical area England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, the Channel Islands and the surrounding territorial waters.

“For over a hundred years the Hero Fund Trust has recognised people who have been killed or injured while attempting to save another human life in peaceful pursuits.

“The Trust also provides financial support, where necessary, to the injured heroes and the dependents of those who have lost their lives.

“Each heroic act is recorded in a beautifully decorative Roll of Honour displayed in the Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum.”

Sweetness and light

Carnegie’s home town of Dunfermline has benefitted greatly from his generosity and the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust continue his legacy through a programme of grant giving and partnership projects to bring more ‘sweetness and light’ to his native town.

Carnegie’s mother laid the foundation stone in 1881 of the first Carnegie Free Library and one of his greatest pleasures was purchasing

Pittencrieff Park in 1902 then gifting it to the people of Dunfermline for their pleasure and enjoyment.

Gillian said: “When he was a young boy, the park was only open to the public on one day a year and, due to his family’s political views, the young Andrew Carnegie was barred from entering it.

“Pittencrieff Park continues to be a major attraction for visitors and locals alike and was voted the best park in Scotland in 2019.

“As well as funding libraries, Andrew Carnegie funded scholarships, science and research projects, church organs, concert halls, universities and museums.

“He supported the founding of internationally renowned landmarks such as the Carnegie Hall in New York, the Peace Palace in the Hague and the Mount Wilson Observatory in California.

“Prior to his death, he had established over 20 trusts, foundations, corporations and centres of education and research across the United States of America, Europe and Britain.

“Today, over 100 years after his death, these organisations continue to carry out their collective missions of promoting peace, education, ethics, culture, science and honouring heroic deeds.”

Freedom of Dunfermline

By the end of his life it was calculated that he had given away over $350m.

He received the Freedom of Dunfermline in 1877 and went on to collect over 50 others from towns and cities throughout the UK.

Carnegie died aged 83 on August 11 1919 at Lenox, Massachusetts.

He was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in North Tarrytown, New York.

Gillian said: “Andrew Carnegie was very aware of the impact wealth could have on society and he stands out amongst other prominent philanthropists of his time, not only because of the vast sums of money that he gave away, but also because he believed there was a moral obligation to do so.

“He firmly believed that the wealthy should use their riches to improve public facilities and enable people to help themselves.

“The following quote sums up Carnegie’s opinion of those who accumulated great wealth during their lifetime but did not use it to benefit others: ‘The man who dies (thus) rich dies disgraced’.”