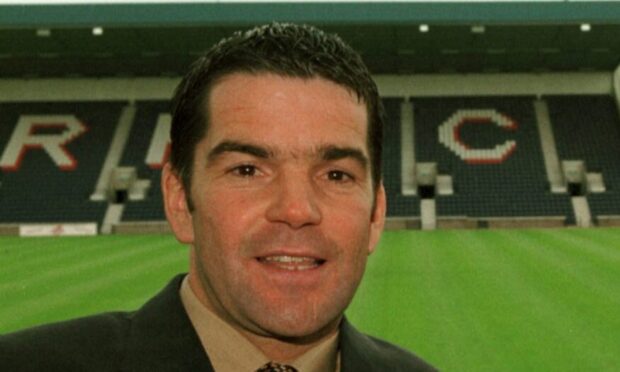

From growing up in Fife to being selected to work for US President Barack Obama, renowned American astronomer Professor Anneila Sargent tells Michael Alexander about her remarkable career.

Professor Anneila Sargent doesn’t make it home to Fife too often these days.

The distinguished astronomer is too busy serving on the United States National Science Board – the team of academics advising Congress and US President Barack Obama – or researching star formation.

But when the California-based academic arrived back in Scotland this week to attend a science meeting in Glasgow and catch up with cousins in Burntisland and Troon, it didn’t take her long to be reminded she was back in the land of her birth.

“When the plane landed it was pretty dreich,” she laughs in an exclusive interview with The Courier.

“Dreich! I hadn’t thought that word for a long time! That’s when I knew I was back in Scotland!”

Professor Sargent, 73, has called California home for 50 years.

The Kirkcaldy-born Edinburgh University physics graduate emigrated to the USA with her late English-born husband Wallace – a fellow astronomer – after he persuaded her to take up a postgraduate position at the University of California.

She moved to the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in 1967 and after raising their daughters Lindsay and Alison, she became professor of astronomy there in 1998.

This led to an unexpected phone call from the White House in 2011 inviting her to serve a six-year term, making her one of six women on the 25-strong NSB.

The professor is admirably modest.

“Don’t ask me how I got on the board!” laughs the winner of the 1998 NASA Public Service Medal who served as president of the American Astronomical Society from 2000 to 2002.

“None of us know how we got on it! I asked someone once and they said ‘you were on a lot of lists’!”

But the professor, who holds dual British and American citizenship, has never forgotten where her remarkable career began – or the inspirational role of her school teachers at Burntisland Primary and Kirkcaldy High School.

She credits her early progress to physics teacher Bill Ritchie. “He kept me in science,” she said.

But she also cites others at Kirkcaldy High School including “very good” female science and maths teachers who were “ahead of their time”.

She says: “I didn’t think about the significance of women at the time, but as I’ve got older, I’ve realised what dynamic interesting lives those teachers were leading. If it hadn’t been for World War Two killing their fiances they probably would have been married and wouldn’t have had careers. These were women you might want to emulate.”

Professor Sargent is grateful for the education she received in Scotland.

But she believes the USA provided her with far more “tremendous” opportunities than the UK would have done allowing her to combine a family life with life as a professional scientist.

A combination of her broad experience of policy, experience in overseeing the construction of astronomical projects like the ALMA space telescopes in Chile and the rise of feminism in the USA helped her “get on”, she believes.

Whilst she has never actually met President Obama, she did meet former President Bill Clinton and cites his administration as one of the most supportive when it came to science funding in the USA.

Yet away from the advisory boards and funding committees, her research passion remains how stars are born and evolve in our own Milky Way and in other galaxies.

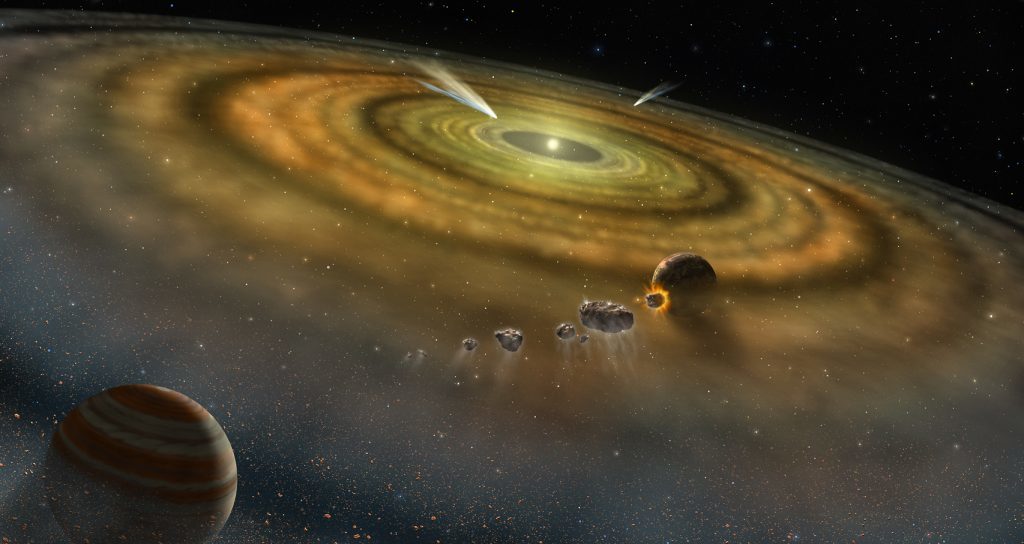

“I look at how new stars are created in the cores of dense molecular clouds of dust and sun – the kind of conditions that surrounded stars like our sun 4.5 billion years ago.

“How do the new stars emerge from this obscuring material;? How is this material itself dissipated? Could planetary systems form around some of these stars?”

Last week data from NASA ‘s Kepler space telescope revealed its biggest collection of new planetary sightings to date – 1284 confirmed planets, along with 1327 additional probable sightings and 707 possible.

Professor Sargent, who has an asteroid named after her, is a firm believer that extra-terrestrial life “could be everywhere” in the universe.

She adds: “There are so many potential systems. I don’t necessarily mean life like us, but regenerative cells. But there’s no reason why there shouldn’t be life like us.”

The professor is excited by the possibility of manned missions to the Moon and Mars in the decades ahead. Yet with the extreme dangers involved, there’s also a growing case for more interplanetary work to be done by robots.

She adds: “One of my grandsons said recently he’d like to get into robotics. I said go for it – that’s the future!”

The professor is “thinking very seriously about retiring in the next year.” She has just stepped down as vice president of Caltech.

Awarded an honorary degree by Edinburgh University in 2008, her “excuse” for travelling to Scotland this time around is as a board member of the Scottish University Physics Alliance, and a meeting at Strathclyde University.

But four years after her husband died, it’s also giving here the opportunity to reflect on life.

Fortunate

She continues: “I went for a walk in Burntisland the other night. It was so sad. The high street was depressed. Kirkcaldy was in the same kind of way.

“Yet when I was here last year, walking on the beach at Dysart, visiting St Andrews and the East Neuk, it was beautiful. I forgot how pretty it was and forgot how rural the interior of Fife still is.

“I am amazingly fortunate to have had an amazing beginning in life here, and to spread my wings to California. Things change in life, but you know what? You’ve just got to go with the flow.”