The last residents of Pitmiddle left more than 80 years ago, abandoning a community inhabited for centuries. Today, what’s left of the village lies in ruins…

In the ruins of an old croft, four walls of rock gradually crumble into the earth. Nettles sprout from a thick carpet of fallen autumn leaves. The remnants of an old fireplace can still be made out. A birch tree sprouts through the spectre of an old doorway. Branches claw at the moss-covered stones. The void of an old window looks out on to wild shrubbery and weeds.

Outside this ruin, the most intact of the homes in the lost village of Pitmiddle, neighbouring buildings have deteriorated to little more than mounds of earth and piles of stones. Some have vanished completely. The modest stream which once proved this community’s lifeblood courses wildly across a muddy plain between the trees.

Where children once played and farmers toiled, a woodland is thriving and nature is reclaiming a lost community.

Pitmiddle: The village that died

“You’d have thought the devil or some ghost had stepped this way, and that the inhabitants had dropped everything and fled – never to return,” wrote Colin Gibson in his Nature Diary in The Courier on February 5 1955, after visiting this very spot.

Another feature on Pitmiddle which featured in sister paper The Evening Telegraph on June 1 1962 ran with a more eye-grabbing headline: “The Village that Died”.

It has been more than 80 years since the last resident of Pitmiddle was forced to leave, abandoning a hilltop community believed to have been inhabited for hundreds of years.

The loss of the village has fascinated locals in the Carse of Gowrie and farther afield for decades; but behind this story of ghostly desolation lies a very Scottish tale of rural life suffering steady and inevitable decline, as relevant today as it was in the 19th century.

An ancient settlement, populated by hardy folk

Pitmiddle first appears on written records around 1172, but its origins are “almost certainly” Pictish according to local historian Gordon Nicoll, of Aberntye.

The hilltop settlement fits the criteria for the Iron Age Scots race, who preferred to live at about 600ft above sea level – safe and away from marshlands.

“Pitmiddle is very old. Certainly Pictish. They had water, they had light, they had a good south-facing slope,” Mr Nicoll added.

“It was a pretty precarious existence. Bad years meant famine and famine meant death. So It was a hard life but that was across the whole of Scotland.”

Typical of communities across the east of Scotland at the time, Pitmiddle would have been an agrarian society, with its inhabitants living off the land often under fear of starvation and famine.

At its peak there could have been between 300-400 people living in the village across a scattering of houses.

‘Horrifying’ living conditions on a Tayside hilltop

Mr Nicoll, who describes himself as an “enthusiastic amateur” historian, has a clear passion for the local area, and channels this through his work running the Abernyte Digital Archive.

He said that early living conditions at Pitmiddle would have been “horrifying to us”.

You were living next door to your cow or your sheep”

Colin Nicoll

In the early days, the homes were single-roomed and shared with farm animals, with one section of the building “screened off” to split families from their livestock.

These properties were either “wattle and daub” or constructed out of rock, with thatched or turfed roofs.

Mr Nicoll said: “You were living next door to your cow or your sheep that you had.

“All domestic rubbish was thrown outside into a midden-heap just outside the door.”

Up until the 1600s, the main crops grown were bere and oats. Flax was also produced there. Life was tough for the crofters, with poor access roads meaning work was mostly done via sledge.

After the 1700s vegetables such as neeps, tatties, peas and beans would have been grown at Pitmiddle.

“Work was never-ending. Crop yields were very poor. What was being grown initially before the 1700s, it was the simple cereals,” said Mr Nicoll.

“Access was difficult. Originally, they didn’t use wheeled carts for the simple reason that that tracks were so heavily rutted that a wheeled cart would have been almost untenable, so they dragged everything with a sledge.

“It wasn’t until you get into late middle 1700s that the roads were improved to the point where wheeled carts were possible.”

The decline of Pitmiddle

The decline of Pitmiddle began as early as the 17th century.

With the onset of the industrial revolution, more and more country folk left their rural lives seeking better fortunes in the cities.

Pitmiddle residents were among those departing to seek new lives in Dundee, Perth and further afield.

“The decline probably started in the 1600s,” said Mr Nicoll.

“And the changes that occurred in the 1600s saw a drift of the population away from the small agrarian hamlets into larger settlements.

“It isn’t until you start to see the beginning of the industrial revolution that people started to move and they moved into the big towns for work because there just wasn’t a living to be made on the land.

“For this area Dundee became the draw, Dundee and Perth, but certainly Dundee because it had the mills.

“Of course the promise of a better life is always there, so as soon as the industrial revolutions starts in earnest the drift is inevitable. People leave the land and head for the cities. And that’s irreversible.”

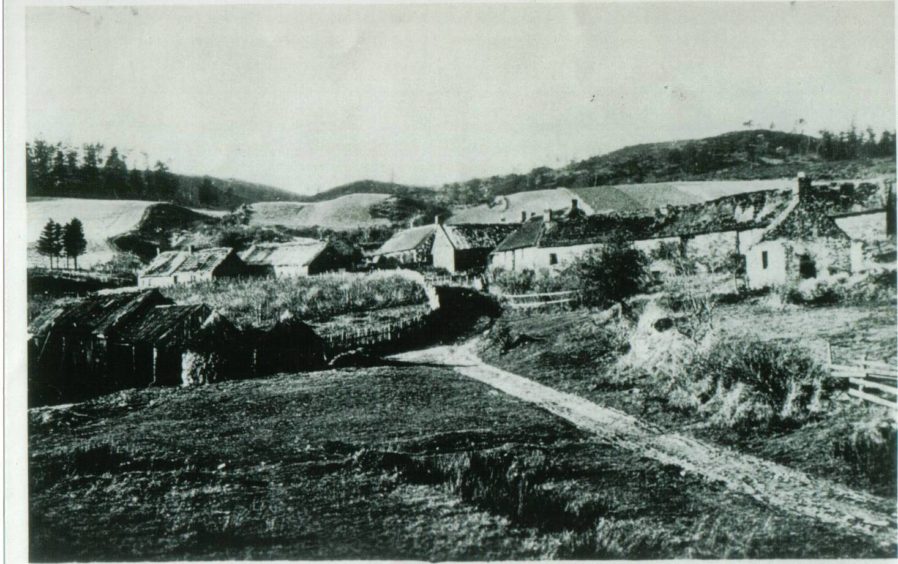

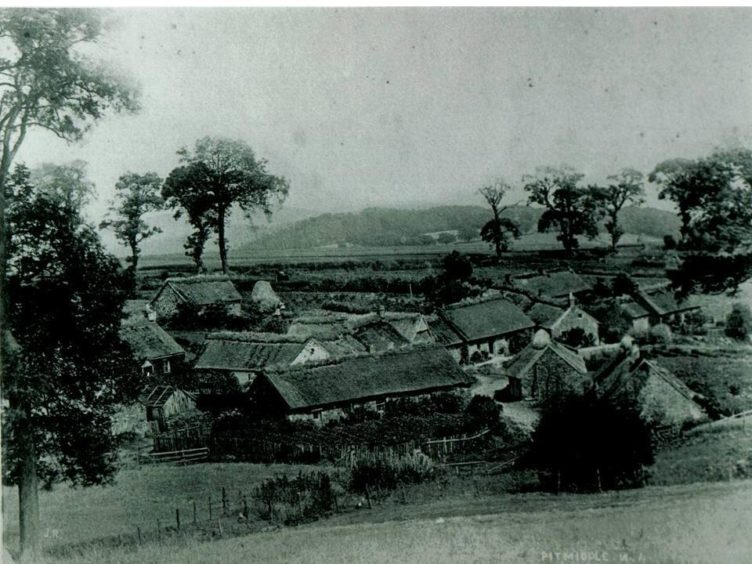

In the 1800s, the decline was so bad that all of the homes in the village were rebuilt in roughly hewn stone in an attempt to halt it.

By 1861, all of the buildings had two rooms with windows. One property had three rooms.

Ultimately the regeneration of Pitmiddle failed and by 1891 there were only 32 people left.

The last inhabitants of Pitmiddle village speak

An article was printed in The Courier on Saturday, December 26 1896. Its headline read: “Decay of a Perthshire village: Weeding out the crofters”.

It contained a detailed account of a journalist’s journey to visit the remaining residents of Pitmiddle as part of an investigation into reports that residents were being evicted from their homes.

The writer did not find clearances of the scale which had taken place in the Scottish Highlands. Instead he found a tiny settlement “gradually going to decay from inherent causes”.

The journalist painted a colourful but sad portrait of a community reduced to just seven families, almost all elderly, living in the ruins of a once happy and prosperous place.

“Not a soul was to be seen,” was how the writer described the arrival in Pitmiddle.

“Silence and desolation reigned around. Many of the cottages were dilapidated and tenantless.”

The residents spoken to by the author were named as the “Widow Gray”, James Gillies, and “Old Maisie Mitchell and her sister”.

While these villagers were not being forcibly evicted, they harboured ill feelings towards their new landlord, who they claimed had given up on Pitmiddle. They felt residents were being phased out of their homes so that the buildings could be cleared for farmland.

However according to the interviewees, Pitmiddle had prospered for a time in the 1800s before its demise.

The Mitchell sisters, the article states, recalled “the time when Pitmiddle was a busy, happy place”.

Mr Gillies remembered the Pitmiddle of his youth: home to 40 crofts and with work to be found in handloom weaving.

He said the town centre had been home to a blacksmiths, two joiners, a shoemaker, a tailor, a butcher and even a pub. Though there was no church, schooling had been provided by the shoemaker; who taught the local youngsters how to read.

Ultimately, lack of farm work and immigration to other parts of the UK, and to America, were blamed for the desertion of the community.

The writer concluded: “And now this once happy and contended little community is breaking up…but the same principles are at work all over the country. The rural population are being driven to the large towns or the Colonies, and the country is becoming a desert as far as human beings are concerned.”

In the early 1900s, the neighbouring farm of Guardswell was let to Dundee merchant John White. He sub-let two Pitmiddle crofts to locals and let out the others as holiday accommodation to fellow city publicans.

However it was the Great War that ultimately sealed Pitmiddle’s fate. Once surrounded by a thriving woodland, the war effort called for these trees to be clear-felled.

The damage to the village’s access roads and its watercourses – once noted by Victorian tourists as being exceptionally clear and pure – was irreversible.

Mr Nicoll said: “The act of clear-felling the wood utterly ruined the access roads and the watercourses on Pitmiddle, which was probably one of the major factors that saw its complete collapse.

“There is no way back.”

The last man leaves Pitmiddle

The last inhabitant of Pitmiddle was another James Gillies, the son of the man quoted in the 1893 Courier article. Many of his family members had emigrated to Canada at the turn of the century, but he remained, clinging to his home and his way of life on the Tayside hilltop until the bitter end.

Eventually, James’s isolated existence could no longer continue. On January 4 1938, a roup was scheduled to take place in Pitmiddle. All of his unwanted possessions were laid out and made ready for sale when fate intervened. A major snowstorm swept in, leaving roads and paths buried.

The roup was abandoned.

James took one last glimpse of his home – that of generations of his family, a settlement which held strong through centuries of change and hardship – before leaving it forever.

He was Pitmiddle’s last inhabitant.

Scotland’s most rural areas still in decline

“This village is about deserted…the school at Kinnaird is almost deserted, and so is the kirk,” Pitmiddle resident James Gillies Snr told The Courier in 1896.

“The smith had to leave for want of work, and our grocer is nearly starved out.”

His words, it would seem, remain eerily prescient in a modern context.

Some 48.7% of the country falls under what is known as the Sparsely Populated Areas of Scotland (SPA).

This covers rural regions and small towns within the Northern Isles, Western Isles, the Highlands, Argyll and Bute, and the Southern Uplands.

Only 2.6% of the country’s population live within this SPA, which in recent years has been the subject of Scottish Government-funded studies by the James Hutton Institute.

Research published by the institute in March 2018 claimed that the SPA was at risk of losing more than a quarter of its population by 2046, if trends stay the same.

The report projected a decrease in population within the SPA from 137,540 in 2011 to 132,000 by 2021 and 99,350 by 2046.

Publishing the data in March 2018, lead author of the report Dr Andrew Copus of The James Hutton Institute, said: “Scotland’s sparsely populated areas have a demographic legacy which, in the absence of intervention, will result in decades of population decline, and shrinkage of its working age population on a scale which implies serious challenges for economic development.”

He concluded: “If no action is taken, this may have serious implications for the workforce, the economy, and the capacity for demographic regeneration.”

It should be noted that the National Records of Scotland’s most recent population figures for the country for mid-2018 offers a different perspective.

The report showed that migration was the biggest driver of an increase in Scotland’s population to 5,438,100 in 2018 – a 0.2% increase.

The figures – which include natural change (births minus deaths) – also revealed that in 2018, 37,000 people left Scotland for the rest of the UK, with 47,700 moving into Scotland from else where in the country.

Some 22,000 people left Scotland for overseas in 2018, 2,500 more than in 2017, while 32,900 people moved into the country from abroad.

However some of the council areas which experienced population decreases in were the most rural including: Angus, (-0.21%), Moray (-0.27%), Aberdeenshire (-0.13%), Na h-Eileanan Siar (-0.45%), Argyll and Bute (-0.63%) and Inverclyde (-0.77%).

Conversely the population of the Highlands increased by 0.15% with the Orkney Islands seeing a 0.86% increase.

Mr Nicoll agrees that the factors which led to Pitmiddle’s demise are “not consigned to history”.

He added: “The draw of the big city on small communities is always there. The young leave and don’t return.

“Fortunately in western Scotland that is being addressed. People are beginning to think about how we keep the local communities, how we keep smaller communities viable.”

A neighbour’s perspective of Pitmiddle

Guardswell Farm, nestled a short walk down the hill from Pitmiddle, is one of the closest dwellings to its ruins.

Boasting better access and stunning views across the Carse, Guardswell survived the abandonment which claimed the neighbouring crofts.

However the villagers of Pitmiddle are never far from the thoughts of the Lamotte family.

“It is amazing how nature takes something back so quickly,” said Anna Lamotte, who runs Guardswell Farm with her parents Fiona and Richard and sister, Kirsten.

“We have been here since 2011. My parents bought Gaurdswell when I was in my late-teens. To be honest I didn’t know about it (Pitmiddle) then.

“It is pretty cool to go up there and look at the redcurrants and gooseberries.”

Ms Lamotte says a “handful” of people stop by Guardswell every year seeking Pitmiddle, and many of them have ties to the community.

“You tend to get people going up that had some sort of connection to it,” she added.

“Maybe a handful a year. We had one group come, a walking group, they did a walking tour up there. There is a wee bit of interest.”

The family farm has in recent years been transformed into a venue used for weddings, rural events and workshops.

Guardswell also offers accommodation for visitors in hillside huts near Pitmiddle which carry names such as The Pendicle and The Kailyard – titles inspired by historic documents on the village.

For Ms Lamotte, the experience of living next to and visiting Pitmiddle isn’t a melancholy one.

“It is sort of magical,” the 29-year-old said.

“It is definitely strange. For me it is more interesting to think about the decision to abandon the community I guess.

“For a lot of the families it must have been quite a big decision.”

‘The shadow of a community’

The village of Pitmiddle is being reclaimed by mother earth.

The last visible traces of the villagers are the crumbling walls of their homes and the wild redcurrant and gooseberry bushes which once grew in their gardens.

Soon, there will be nothing left.

“It is becoming part of the landscape again”, said Mr Nicoll.

“There is very little to see now. And within a very short space of time I think that will be gone too and we’ll have forgotten of Pitmiddle.

“The echoes of the houses are still there, although with each year that passes the land has reasserted itself, the weeds are growing up around about them, the weeds and the nettles are growing over them.

“The track you can make out if you go at the right time and the weeds have died down. The wells have more or less filled in now. You can’t really find them.

“It is the shadow of a community now.”

Viewed from a distance, Pitmiddle looks no more than a scattering of trees on the slopes of Pitmiddle Hill.

It feels remote, isolated, but those who know where to look can glimpse the treetops from the laybys of the A90.

Pitmiddle’s remarkable views across the Carse of Gowrie, to Dundee, the Sidlaws and the hills of Fife, are a stark reminder of how close this village was to the outside world.

So how is it that Pitmiddle died while neighbouring villages and hamlets, where residents surely faced similar hardships, survived?

“Change”, answers Mr Nicoll.

“Change that comes too quickly and swamps the very reason that you have a community there. Which is what happened at Pitmiddle.”