On the 15th anniversary of the G8 summit at Gleneagles, warnings have been sounded that global poverty could be set back decades by Covid-19. So will poverty ever be history? Michael Alexander reports.

Fifteen years ago this week, the G8 summit saw leaders from the USA, Canada, Russia, France, Italy, Germany and Japan join the then UK prime minister Tony Blair at Gleneagles in Perthshire where they discussed development in Africa and global climate change.

As hundreds of thousands marched vociferously in Edinburgh and Auchterarder demanding that the richest nations “Make Poverty History” – and despite events being overshadowed by the 7/7 London bombings – the summit ended with an agreement to boost aid for developing countries by $50bn (£28.8bn) and to cancel the debt of the 18 poorest nations in Africa.

On trade, there was a commitment to work towards cutting subsidies and tariffs, while on climate change, the US accepted, for the first time, that global warming was an issue.

Fifteen years down the line, there have been encouraging trends with global “extreme poverty” at its lowest ever recorded level by 2015.

But with charities like Oxfam warning that the richest nations are continuing to fuel global inequality, with extreme poverty again on the rise – especially in Africa – and underfunded health systems in the world’s poorest nations woefully ill-prepared to deal with the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, will poverty ever be history?

Jack McConnell – now Baron McConnell of Glenscorrodale – was First Minister of Scotland at the time of the 2005 G8.

The Labour peer remembers an “incredible” week that presented an opportunity to show case Scotland internationally, while the event itself was historic as a focus for rich countries to “step up their game” to help the poorest.

With the Make Poverty History (MPH) movement driven by peaceful ‘people power’, he’s still in awe at the “truly phenomenal” role of police who quelled the actions of a small number of hard core Italian anarchists intent on “smashing up” Edinburgh.

But Lord McConnell , who now chairs the all-party parliamentary group on UN sustainable development goals at Westminster, concedes that while the 2005 G8 “made a difference”, it was not enough.

With the link between conflict and violence on one side and extreme poverty on the other continuing, he is urging the G8 (now the G7) to “show the same commitment and concern for the world’s poorest” when they meet in the USA in September to recommit to goals set in 2015.

However, he is also “deeply concerned” about the impact the Covid-19 pandemic is having on the world’s poorest.

“We could see the first rise in extreme global poverty in our lifetimes,” he said.

“Extreme global poverty has been steadily coming down – the national, local and international action has been working.

“But the pandemic could be the thing that reverses that trend.

“That’s why we need leadership from the United Nations, we need leadership from the G7 and we need to understand we can’t combat pandemics in the same way we can’t stop wars if we just look after ourselves.”

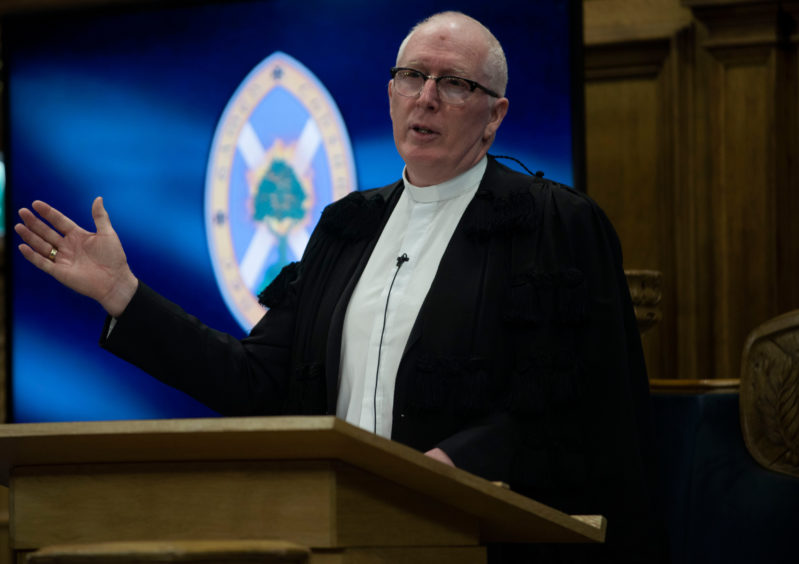

Recently appointed Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, the Rt Rev Dr Martin Fair of St Andrew’s Parish Church in Arbroath was “100% involved” in the G8 back in 2005 with social justice and development events held by the church in Angus and a “bus load” going down to Edinburgh for the MPH march.

Although serious subjects were at stake, he recalls the MPH campaign being a “joyous time” of common purpose trying to improve the lot of the planet’s poorest irrespective of geography, nationality, race or religion.

In 1990, more than a third of the world population lived on $1.90 a day or less. This compared with 2015, the most recent year with robust data, when extreme poverty reached a record low of 10%.

However, with at least 736 million people still in “grinding poverty”, the poverty rate in conflict zones climbing to 36% in 2015, rising global populations, climate change and now the impact of Covid-19, Rev Fair says there’s no room for complacency and much work still needs to be done.

“We are already seeing and hearing stories of the pandemic affecting countries with less developed primary and public healthcare infrastructure,” said Rev Fair, 56.

“Where people are not able to work due to lockdown, but in countries that can’t afford social security, job retention schemes or business bailouts – there could be a real risk of recession, employment, hunger and unrest.

“The other big issue is the climate emergency, which disproportionally affects people living in less developed countries, who contributed least to global carbon emissions. The (re-scheduled) COP26 UN climate meeting in Glasgow next year has to address this injustice.

“It is no longer simply a question about how we care for creation, but how to find a way to enable every person to enjoy a life in all its fullness.”

If ever there was a local boy with an international perspective on the 2005 G8, then it’s award-winning writer, poet and broadcaster Robin Bell.

Born and raised in Auchterarder, he lived in New York and London for many years, but was back in his native village for the summit to capture the mood.

He produced a Creative Scotland-funded book called ‘How to Tell Lies, The G8 Handbook’ which “showed politics at its maximum of harmonious smiles and minimum accountability”.

Fifteen years on, and Robin says it’s “almost incredible” to think that in 2005, the USA was only just acknowledging there might be a link between human activity and climate change.

But he says the lessons from the G8 and how governments operate are as relevant to today’s crises as they were then.

“Will poverty ever be history? The short answer is no!” he said.

“You can argue that the eight countries of the G8 – now the G7 – is nothing like enough for a debating platform for serious global discussion. That’s one thing that’s not been learned. Here, the gulf between rich and poor is growing, and educational challenges remain.

“But you also have to understand how governments operate. If you are out of office and want to get elected you wave ‘prescriptions’ to the public for stimulus.

“If you are in government and want to remain in power, you prescribe ‘sedatives’.

“What has to happen for change is for someone to do some stirring so a population that’s mildly ‘sedated’ is sufficiently stirred to demand genuine change.

“These effects can be quite short lived. For example, this time last year we were all talking about Greta Thunberg. She’s not hitting the headlines so much now – until recently – so were her efforts in vain? No, I don’t think so.

“You have to see the G8 like that. It was high profile, it raised awareness and it did things like encourage governments to invest money in scientific research and in poverty programmes.

“But you can’t expect any government programme to remain valid for more than a year or two.

“It’s got to be reviewed, updated and adapted to changing circumstances.”

One of those “stirrers” who facilitated change was Jamie Drummond, co-founder of One – a global movement campaigning to end extreme poverty and preventable disease by 2030, so that everyone, everywhere can lead a life of dignity and opportunity.

Working with musicians Bono and Bob Geldof, he was “in the thick of it” at the 2005 G8 – helping to organise the MPH marches and the worldwide ‘Live 8’ concerts that preceded it.

Significant global material changes he points to since 2005 include the reduction of child mortality amongst under-5s by three million per year, a halving of deaths from HIV/AIDS, a 50% reduction in malaria and significant child poverty reductions resulting from campaigns “MPH gave a voice to”.

However, Jamie said the “fight is on all over again” due to Covid-19.

“It’s a heavy moment,” he told The Courier, adding that he’s worried about the government announcement the other week that the Department for International Development (DfID) will be merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO).

While all for British products being sold abroad, he said keeping an independent DfID is the best way to ensure aid is spent on helping those most in need and remains untied to political interests.

He added that with a G7 scheduled for the UK again next year and the rescheduled COP on climate in Scotland, many campaigners are eager to partner with people across the country to come together for people and planet in a way that “builds back better” from Covid-19 and “learns from the successes and mistakes” of past campaigns like MPH.

Alistair Dutton, director of the Scottish Catholic Aid Fund, said SCIAF was proud to take a leading role in the MPH campaign in Scotland – standing up for the world’s poorest people.

However, poverty and inequality is still with us. The legacy of MPH, he said, is that there remains a “tremendous appetite” for a fair and just world.

“As we face a world ravaged by the coronavirus and climate change, the need is more urgent than ever,” he said.

“The pandemic has brought into sharp focus the huge inequalities that exist and without doubt many poor countries will be forced further into poverty.

“This is why SCIAF, together with other charities, is also calling for debt cancellation for poorer countries again so they have a fighting chance to survive these crises.”

Sally Foster-Fulton, head of Christian Aid Scotland said MPH “woke up the world” to global poverty and the crippling debt repayments that make it so difficult for many countries to move forward.

As a result, £130 billion of debt was wiped for 36 of the world’s poorest countries.

But 15 years on, debt and many other unjust economic issues, like corporate tax evasion, are still huge problems. Before the Covid 19 crisis, 64 low and lower-middle income countries were spending more on external debt payments than healthcare.

“How are they expected to respond when lack of finance on infrastructure means they are struggling from the start?” said Sally.

“This is an unrecoverable position in any health emergency and will strangle any progress made.”

The MPH march in Edinburgh remains the largest anti-poverty march in Scottish history. That’s a legacy in itself, she added.

But it’s a legacy that must be kept alive – especially at a time when the coronavirus pandemic reminds us not only how inter-connected we are on planet Earth, but also how unequal the world is.

She also warned that climate change is making it even harder for the world’s poorest countries.

“In the words of one of our partners, ‘Forget making poverty history, climate change is making poverty permanent,’” she added.

But of course, poverty is not just a global issue – it also exists at home.

Two weeks before the Make Poverty History march focussed on global poverty, Dundee man Ewan Gurr helped pioneer Dundee Foodbank in response to food insecurity in the city.

The then 19-year-old, who went on to spend 14 years helping to set up and run foodbanks across Scotland – including seven years as Scottish manager of the Trussell Trust – decided he wanted to ‘make local poverty history’.

Pointing to the impact of the 2008 financial crash and the enabling of the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition at the 2010 general election, a legislative cornerstone of this new era was the Welfare Reform Act 2012 which included spare room subsidies referred to as the Bedroom Tax, tightening of the stringency around benefit sanctions and Universal Credit.

The result? Poverty soared in Scotland and foodbank use leapt 400% in the year this political vision became a social reality.

“As I did in 2005, I often ask if we can make poverty history,” said Ewan.

“Dundee Foodbank was intended as a short-term effort but just celebrated – or commiserated – its 15th birthday.

“Poverty is multi-faceted so it is too simplistic to suggest, as some do, that more investment means less poverty.

“More broadly, I believe that to make poverty history, we need to make poverty personal.

“We must feel it to truly understand it and our response, socially and politically, should then be shaped by that knowledge.”