His daring raid on Westminster Abbey has become the stuff of legend, and reinvigorated a hunger for Scottish independence.

Ian Hamilton described his group’s capture of the Stone of Destiny in 1950 as a “liberation” not a theft, and looks back on the episode as a symbolic show of national pride.

But nearly 70 years on, and Mr Hamilton has said he is finished fighting for the Stone of Scone.

The 93-year-old said he would be happy to see the ancient treasure returned to Perthshire, but would prefer to stay out of the on-going debate on its future home.

“As long as it stays in Scotland, that’s all I care about it,” he said.

The Courier is campaigning for the artefact to move to Perth, to become the centrepiece of a new £23 million city centre museum.

Perth and Kinross Council launched its bid for the stone three years ago, claiming the iconic sandstone block could help bring in hundreds of thousands of new visitors to the Fair City.

Historic Environment Scotland launched a courterbid to keep the Stone kept in Edinburgh Castle.

Mr Hamilton, who was ringleader of the famous Christmas Day Westminster operation, insisted he does not have strong feelings about where the Stone ends up.

“I’m not the keeper of the Stone of Destiny,” he said. “I don’t really care what happens to it as long as it doesn’t leave Scotland. As long as Betty Windsor and her family don’t get their hands on it.

“I’m certainly not against it coming to Perth, but I want to remain neutral about this.”

He said: “Seventy years ago it was a symbol. But we don’t need symbols now, because we’ve very nearly got the reality of Scottish independence.”

Mr Hamilton wrote a book about his leading role in the Westminster Abbey raid, which was turned into a film in 2008.

“The whole thing was a romantic adventure”

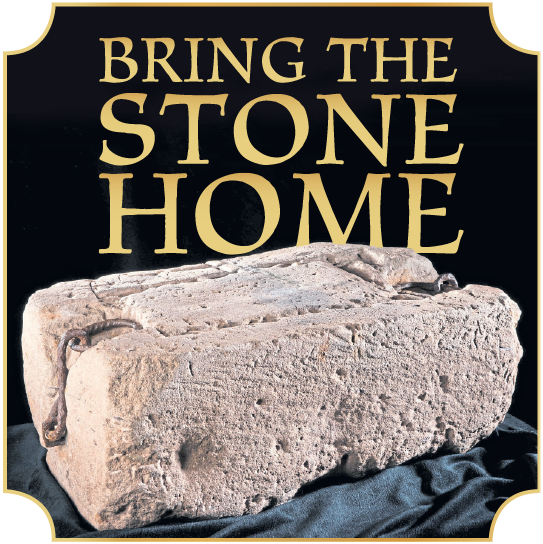

The Stone of Destiny – the ancient crowning seat of Scottish kings – was swiped from Westminster Abbey in the early hours of Christmas Day, 1950.

The original plan was to remove it two days earlier.

Ian Hamilton was supposed to lock himself inside the church with tools hidden in his clothing. He was going to unscrew the locks on one of the doors and let the rest of his group – fellow students Gavin Vernon, Alan Stuart and Kay Matheson – inside.

He was disturbed by a nightwatchman and had to talk his way out of trouble. The students returned two nights later.

Mr Hamilton, who went on to spend more than 50 years as one of Scotland’s most respected QCs, waited for the church to be left in darkness before making his move.

He took a crowbar to the a side door and jemmied the lock.

“We knew where the Stone was,” he told the BBC World Service in December. “It was kept under a coronation chair, a chair that had been made especially for it.

“There was a hollow ledge underneath that we had to prise the stone out from.”

Weighing 150 kilos, the group dropped the relic, breaking it in two.

“I would like to say that I was terribly overawed about having broken the Stone of Destiny,” he said. “But I wasn’t. I was glad because with a quarter of it away, it made it easier to handle.”

Mr Hamilton carried it out to a parked Ford Anglia with Ms Matheson. When they were approached by a police officer, they pretended to be a young couple in love.

In the days following the raid, a massive police search was launched. Investigators believed that the Stone may have been dumped in the Serpentine lake in Hyde Park.

Mr Hamilton said: “Everyone believed (what we did) was impossible, and once the impossible had been done, they were looking for a very remarkable man.

“But I’m just an ordinary person who wanted to do something for my country.”

As time past, fears grew that Scotland could lose the Stone altogether. It was decided to leave it in the ruins of Arbroath Abbey.

The artefact, which had been put back together by a stonemason, was picked up by police in time for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation.

“I don’t consider that retrieving my country’s property was breaking the law,” said Mr Hamilton. “After all, the Home Secretary said at the time that we would not be prosecuted.

“He referred to us as ‘these vulgar vandals’ and that has been one of my favourite phrases ever since.”