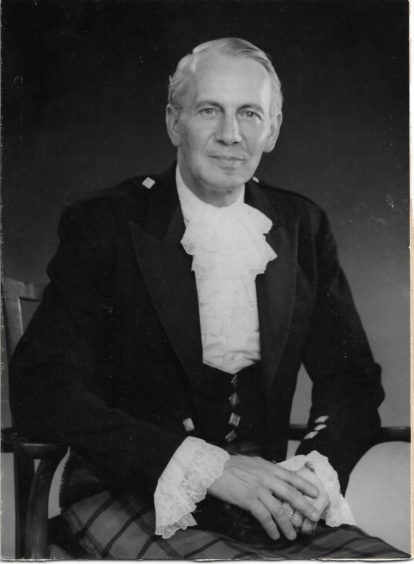

Michael Alexander speaks to Andrew MacThomas of Finegand about his family’s Glenshee roots as he marks his 50th anniversary as the 19th Chief of the Clan MacThomas.

It was a dangerous time of grit and determination when Highland Scotland’s ancient and proud tribal families eked out an existence off the land – sometimes becoming embroiled in bloody feuds with their neighbours in disputes over cattle and borders.

Today, Scotland’s clan system is usually associated with the past – its demise in the 18th century mentioned in the same breathe as Culloden, Jacobites, the Highland Clearances and other oft romanticised recollections of a tartan-clad world wiped out by the forces of politics, religion and ultimately the sword of the Crown.

But with internet-led genealogy and a populist, not always entirely accurate, version of Highland history portrayed through TV shows such as Outlander and Game of Thrones, a renewed international interest in clan culture is showing a strong resurgence amongst Scotland’s 40 million strong diaspora which, in pre-Covid times, was worth millions of pounds to the modern Scottish tourism industry.

One man with a keen interest in Scottish history – and living proof that clan heritage is of great importance to modern 21st century Scotland – is Andrew MacThomas of Finegand.

In May he celebrated 50 years as 19th Chief of the Clan MacThomas whose traditional lands are situated in the wild and open spaces of Glenshee, Perthshire.

With just five other clan chiefs having reached this half-century milestone, the clan chief role today is, of course, a largely ceremonial one.

Alongside regular gatherings at the Cockstane (Clach na Coileach) – the traditional gathering ground of the Clan MacThomas in Glenshee – he had the honour of performing with a group of modern day clan chiefs at the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo in 2017, and has also been proud to uphold the heritage of his ancestors over the years through visits to Scottish diaspora events in Australia, Canada and the USA.

However, becoming clan chief had not been an imminent part of Andrew MacThomas’ lifeplan when he took on the role as a 27-year-old in May 1970.

At the time, the Edinburgh-raised former public school boy was a single man working for Barclays in London.

When his father Patrick MacThomas succumbed to illness on May 9, 1970, it meant Andrew was faced with the daunting responsibility of becoming chief of a modern Scottish clan.

“I had mixed feelings about it,” says Andrew, now 78, whose day job saw him spearhead the Barclaycard credit card revolution in Edinburgh during the 1970s, before eventually becoming director of public affairs for the Barclay’s group.

“I’d lost my father who died when he was only 60. Secondly, to be honest, I hadn’t taken a huge amount of interest in it up to then.

“Until I was about 15, the chiefship was not even in my family, so as I grew up I didn’t expect to be a clan chief. When it came it was all a bit of a shock!”

Andrew explained that the MacThomas chiefship had been in abeyance for around 200 years having been classed as a “broken clan” since the end of the 17th century.

His grandfather put in a claim for it “that took years and years” and didn’t come through from the Lord Lyon until 1957, by which time his grandfather had died.

Andrew’s father, who was keenly active on promoting clanship through the then embryonic Clan MacThomas Society (est 1954), became the first official MacThomas chief in two centuries. However, he then passed away after just a few years in post.

“I had to decide what to do,” says Andrew, who recalls how there was a growing worldwide interest in clan roots after the Second World War.

“I could walk away, which I could have done, or I could do one’s duty for want of a better word and get stuck in and try to do something as well as I could which is what I tried to do.

“I’m very pleased I did because it has led me to areas I probably would not have got into.

“I’ve met a lot of wonderful people and been to some areas of the world I would probably never have gone to where the Scottish diaspora is huge – 40 million of Scottish descent around the world.”

The story of the MacThomas clan is a fascinating one that is entwined with the twists and turns of history through the centuries.

The clan is descended from Thomas – a Gaelic speaking Highlander known as Tomaidh Mor (‘Great Tommy’) – who was a descendant of the Clan Chattan Mackintoshes, his grandfather having been a son of William, 8th Chief of Clan Chattan.

Thomas lived in the 15th century, at a time when the Clan Chattan Confederation had become large and unmanageable and so he took his kinsmen and followers across the Grampians, from Badenoch to Glenshee where they settled and flourished, being known as McComie (phonetic form of the Gaelic MacThomaidh), McColm and McComas (from MacThom and MacThomas).

They made a life for themselves there, but it must have been unbelievably tough in those early days, because they lived above the treeline.

“Imagine in the winter time just trying to survive by being beside the rocks, boulders and crevices and trying to make a way for themselves – going into the woods at night to try and get game? It’s unbelievable really,” reflects Andrew.

To the government in Edinburgh, they were known as MacThomas and are so described in the Roll of the Clans in the Acts of the Scottish Parliament of 1587 and 1595 and MacThomas remains the official name of the clan to this day.

The early chiefs of the Clan MacThomas were seated at the Thom, on the east bank of the Shee Water opposite the Spittal of Glenshee, the site thought to be that of the tomb of the legendary Diarmid of the Fingalian saga, with which Glenshee has so many associations.

In about 1600, when the 4th Chief, Robert MacThomaidh of the Thom was murdered, the chiefship passed to his brother, John McComie of Finegand, about three miles down the glen, which became the seat of the chiefs.

Finegand is a corruption of the Gaelic ‘Feith nen Ceann’ meaning ‘burn of the heads’ and refers to the time when some tax collectors were attacked by some clansmen, who cut off their heads and threw them in a nearby burn.

By now, the MacThomases had acquired a lot of property in the glen and houses were well established at Kerrow and Benzian with shielings up Glen Beag.

The time was spent breeding cattle and fighting off those seeking to rustle them, one such skirmish, in 1606, being remembered as the Battle of the Cairnwell.

During the time of the 7th Chief John McComie (Iain Mor) –a Highland legend who is still talked about in the glen to this day – the clan extended its lands and influence into Glen Prosen and Strathardle and Iain Mor purchased the Barony of Forter in Glenisla from Lord Airlie.

However, when Iain Mor, “for all the right reasons at the time” decided to support the protectors of Cromwell, “because Cromwell brought law and order and prosperity to Scotland” this soured his relationship with Airlie.

On the restoration of Charles II in 1660, he found himself in trouble with parliament, who fined him heavily and at Airlie’s instigation a law suit decreed that the Canlochan Forest, part of the Forter estate, belonged to the latter.

Iain Mor refused to recognise it, continuing to pasture his cattle on the disputed land which Airlie had leased to Robert Farquharson of Broughdearg. This led to a bitter feud culminating in a skirmish at Drumgley, just west of Forfar, where at a spot, now known as McComie’s Field, Broughdearg was slain on January 28, 1673, along with two of Iain Mor’s sons.

The fine, feud and the crippling law suit that followed ruined the MacThomases, and following Iain Mor’s death, his remaining sons were forced to sell their lands – leading to the break-up of the clan.

Andrew insists there are no grudges held between the clans to this day. “I have very good relations with the Farquharsons who we skirmished with over the decades,” he says.

Perhaps the greatest legacy, however, is the genealogical variations of the MacThomas surname that have passed down the centuries.

For example, those who settled in the Tay valley changed their name to Thomson and those in Angus and Fife became Thomas, Thom or Thoms.

Andrew’s direct ancestor the 10th Chief, Angus, who took the surname Thomas and later Thoms, settled at Collairnie in north Fife where his family thrived as successful farmers until they moved to Dundee and became prosperous merchants, at the end of the 18th century, finally buying the estate of Aberlemno near Forfar.

Others moved north into Aberdeenshire, where the name became corrupted to McCombie as well as the anglicised forms Thom and Thomson.

Andrew’s great great grandfather Patrick Hunter MacThomas Thoms of Aberlemno, 15th Chief, was Provost of Dundee from 1847 to 1853, while his heir, the eccentric George Hunter MacThomas Thoms, advocate, bon vivant and philanthropist, became Sheriff of Caithness, Orkney and Shetland in 1870, donating during his lifetime large sums to St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh and, upon his death in 1903, his vast fortune to St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall, together with the Aberlemno estate.

Andrew says there are around 300 paid up members of the Clan MacThomas Society today (www.clanmacthomas.org) and about 700 social media followers. Many are in the UK. Most are overseas – mainly North America.

Describing the strength of Scottish allegiance abroad as “refreshing and excellent”, he laughs when he reveals Scottish chiefs are still seen – certainly in America – as “an extension of the British royal family”.

But it’s the visitors who spend millions each year in non-Covid times which helps keep people in the Highlands and Islands in employment.

Although based in England, Andrew – during ‘normal’ times at least – visits Scotland regularly. He has meetings in Edinburgh, family in Fife and Angus and visits Glenshee more than six times a year.

The Cockstane area has been redesigned in recent years with a new car park and native tree re-planting.

The MacThomas Bridge over the Shee Water is also a nod to the past.

More than that, however, when he visits it’s as if he can feel a spiritual connection to his ancestors reaching down the centuries.

“When my children were young we always used to holiday in Glenshee,” he smiles.

“I just felt it was necessary to come up there, throw open the front door in the mornings and let them run around, and they grew to love it.

“Both my son and daughter feel a huge connection to Glenshee. It’s where we come from!

“But Glenshee has of course gone through it’s difficult times. There were quite a lot of people living there at one stage – less so today.

“It’s been difficult for the hotels and hostels in the area to maintain themselves. The events of this year have not helped either, so it’s been tough.”

Andrew says it’s a “great honour and a great privilege” to be a clan chief.

He’s tried to take the role as seriously as possible and do what he can to ensure that the heritage and the traditions and history are maintained for future generations.

He hopes to be around for a good few years yet. But he does try to involve his son Thomas, who lives with his Scottish-American wife in Manhattan, New York.

“He’s very involved in the clan society and I do try to keep him up to date,” he adds.

“I think he’ll be an excellent clan chief when the times comes!”