Michael Alexander speaks to Perthshire man Alan McKirdy who has just completed a near decade-long project to tell the story of Scotland’s fascinating geological past and present.

For a man who graduated with an honour’s degree in geology, worked for 20 years as a geologist, and has written more than a dozen geology books, Alan McKirdy’s love for the subject was a slow burner.

Even when he arrived at Aberdeen University and his advisor of studies suggested that he fill a gap in his first year timetable with geology, he admits he had “no real interest in the subject”.

Taking the subject alongside chemistry, zoology and psychology, Alan recalls how he disliked his first term of geology because it was “all new with difficult and unfamiliar words”.

Seeing things differently

However, when he “suddenly cracked the code” of geology, and started to see the countryside in a totally different light, he viewed the subject as “amazing”.

Instead of seeing “boring old rocks”, he could look at the Cheviots or the Ochils, close to where he lives now, for example, and see the remnants of 400 million year old volcanoes.

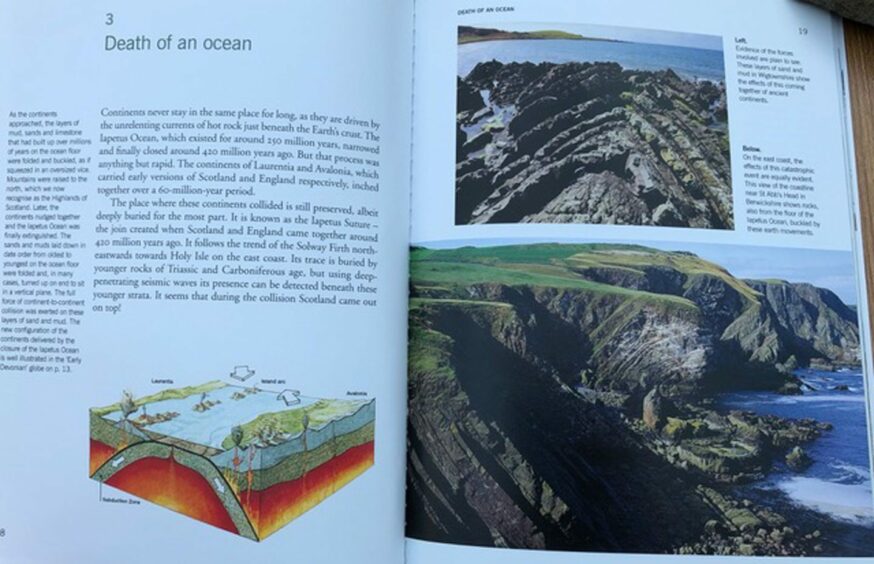

He was able to visualise how what is now Scotland had started life close to the South Pole and had been driven across the face of the Earth by plate tectonics.

This revelation about the ‘long view’ of the landscape and climate was something he found fascinating, and he’s never stopped being fascinated since.

He graduated with a degree in geology and worked initially for the Nature Conservancy Council in Berkshire.

Later in his career he got into management – latterly becoming head of knowledge and information management with Scottish Natural Heritage – the precursor of Nature Scot.

What saddens him, however, is the number of people he still meets who don’t share his ‘big picture’ vision for geology and who think the subject is “boring”.

One of the problems with geology in the past, he says, is that geologists tended to “patronise” their audience with terminology and a “know it all” sense.

New approach

What he’s tried to do since retiring on his 59th birthday just over a decade ago, is put that right.

After releasing the precursor to the rest of his series, Set in Stone: The Geology and Landscapes of Scotland, he set out to write guides on all major regions in Scotland.

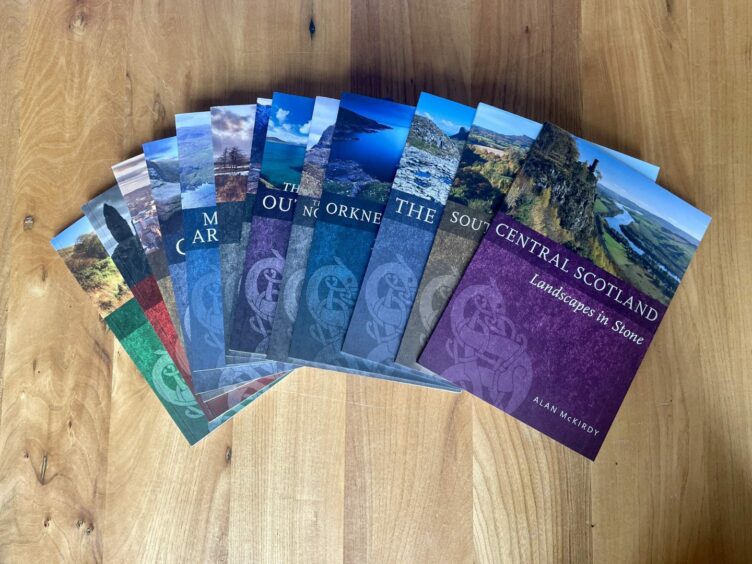

He’s produced a series of 14 Landscapes in Stone books – a collection exploring Scotland’s fascinating geological past and present.

The books, aimed at a general non-academic audience, chronicle the geological history of every major region in the country ranging from the Cairngorms to Shetland and Argyll to the Scottish Borders.

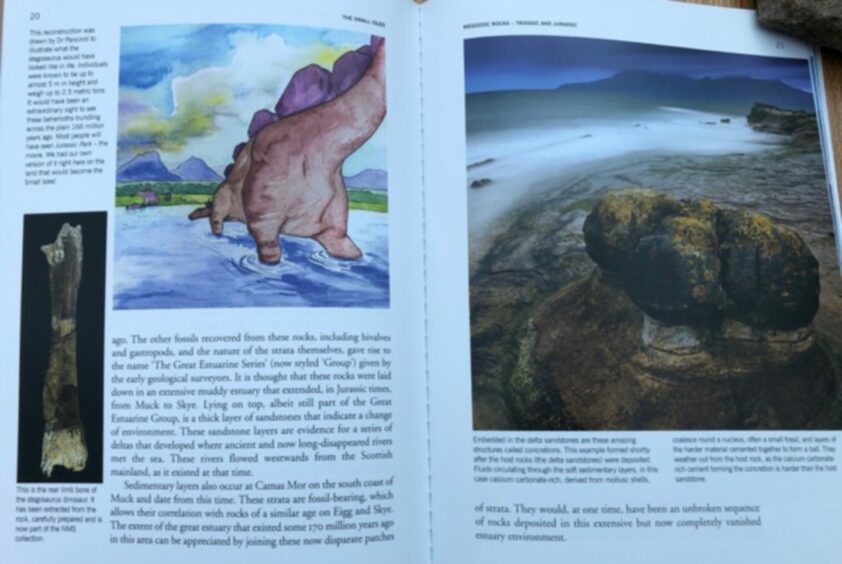

The books are packed with information about Scotland’s iconic landscape.

Crucially, however, not only are they a wealth of information on Scotland’s past, they offer invaluable insight as Scotland’s future becomes increasingly uncertain due to climate change.

“Global warming is by far the most important and critical environmental and geological issue of the day,” says Alan, 69, who grew up in Kelso and now lives in Auchterarder.

“It’s not just something that might happen in the future; effects are right here and right now.

“The Landscapes in Stone series tell of past climates, such as deserts, tropical rainforests and long disappeared oceans that created the bedrock of Scotland.

“We don’t expect such dramatic climatic shifts to suddenly appear, but there will be major changes to our landscapes and coastline millions of years hence.”

Understanding the past

Geology is about understanding the past and to do that effectively, says Alan, there needs to be an understanding of how the world works today; and also how things might change in the future.

The geological period we live in is called the Anthropocene where Homo sapiens (us!) are a significant agent of change for the atmosphere, the hydrosphere and generally of the Earth’s crust on which we live our lives.

It’s a role humans haven’t played particularly sympathetically in past decades.

Humans must become better custodians of our fragile world, he adds.

What he’s tried to do with his series of books is use words, pictures and diagrams together to try and explain Scotland’s amazing geological journey.

Crucially, he wants ordinary people to gain a greater understanding of the landscape around them, wherever they live.

“One of the most amazing stories that I’m aware of in terms of Scottish geology is that Scotland started life close to the South Pole and it’s been driven across the face of the Earth by plate tectonics,” he says.

“That’s how continents move.

“We’ve been through all the various climatic zones of the Earth to arrive at where we are now – 67 degrees north.

“I’ve tried to explain that story in a way that makes people go ‘wow’!

“I do quite a few public lectures and book festivals and after just about every talk somebody comes up to me and says ‘wow I had no idea about any of this’, and that makes me slightly cross because that means that the education system is falling down.

“All these things are well known and accepted in the geological literature, but it’s just that nobody has bothered their backside to try and translate them in a way that you can understand.

“It’s just trying to interpret things in a way that’s relevant to their experience in a way they can understand and connect with.”

Scotland’s last untold story

Alan goes as far to describe geology as one of Scotland’s last untold stories.

He says that as a society we are “very keen on Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Picts and all the historical stuff that we know about”.

He’s concerned, however, that geology is a piece of Scotland’s history that largely isn’t taught in schools.

“It damn well should be!” he says.

“I’m working with the Scottish Association of Geography Teachers to try and get them to change the curriculum to try and get at least plate tectonics into the curriculum because that influences so many geographic phenomenon.

“They used to teach geology as a Standard Grade and Higher but it failed because so few schools took it up.

“I’m not suggesting that we should go back and have Nat 5 or Higher geology again in schools, but relevant bits of geology should be in the curriculum, particularly in the geography curriculum.”

‘Long view’ of geological time

Alan says it’s important to understand the causes and effects of modern day climate change.

However, he also wants people to get as excited as him about the ‘long view’ of geological time.

From understanding how the coalfields of Scotland are the remnants of tropical rainforests when Scotland had an equatorial climate during the Carboniferous period, to imagining how Scotland was completely flooded due to sea level rise during the Cretaceous period – a time when chalk was being deposited in the south of England.

The climate had heated up to the extent that the ice caps at both poles completely melted.

“Everyone just assumes that the coastlines have always been where they are at the minute,” he says.

“The coastlines have zipped back and forward according to the nature of the climate to which the country was being subjected at the time, and the hotter it is the less ice there is at the poles, therefore the higher the sea levels are.

“That’s something I don’t think many people appreciate – climate change has been going on for hundreds of millions of years.

“Even now we are still in an ice age. Again a lot of people don’t realise.

“We are in an interglacial at the minute.

“With the climate alternating between cold periods and hot periods, the ice advances and retreats from the poles in accordance with the climate at the time.

“The ice melted last 10,000 years ago and these inter-glacials normally last 10,000 years, so we should be plunging back into the next ice age now.

“But because of all the greenhouse gases we’ve pumped into the atmosphere, that’s going to delay the onset of the next ice age by about 50,000 years.

“It won’t really affect us but it’ll affect those that are surviving at that time.”

Encouraging sales figures

With the last three books in the series just released, Alan says the sales figures have been very encouraging.

They’ve been deliberately marketed to have geographic integrity within geographic boundaries.

While hard work to produce, the finished product gives him a “terrific buzz”.

However, he also loves doing book festivals.

“I’ve done Edinburgh twice, Glasgow and six or seven others across Scotland,” he says.

“I’m going up to the St Magnus Arts Festival in Orkney in a month.

“I’ve also been asked to do the opening talk for the Scottish Geology Festival which is an honour.

“At times it’s been a slog, Sometimes I don’t enjoy it. But I enjoy the fulfilment of having done it!”

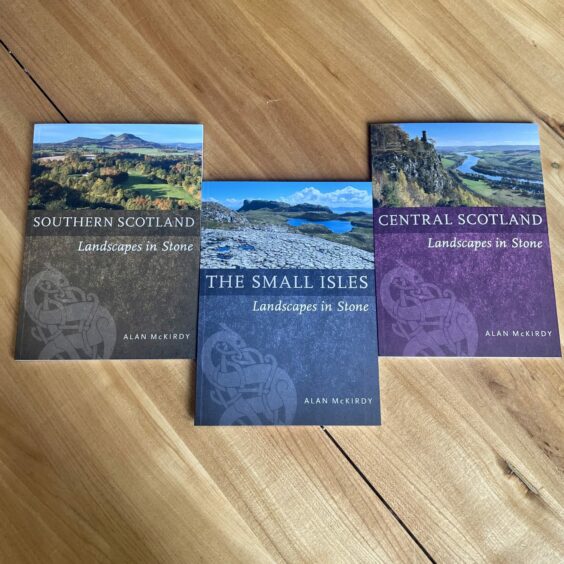

The last three in the Landscapes in Stone series – Central Scotland, Southern Scotland, and The Small Isles – were published by Birlinn on May 5.

Conversation