Ian Imrie went from a basic upbringing in Perth to becoming a self-proclaimed billionaire via mingling with superstars such as Jimi Hendrix and Paul and Linda McCartney.

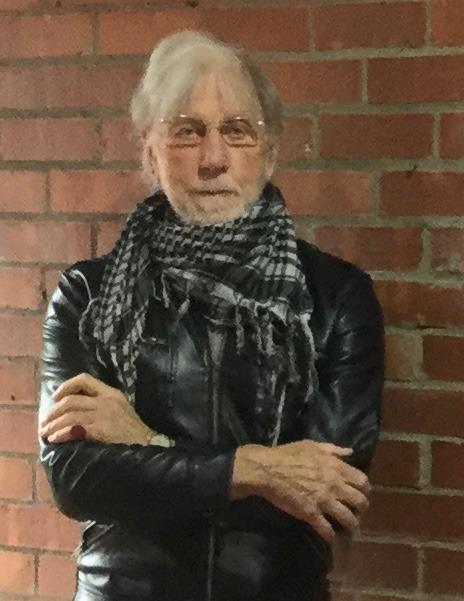

In recent years the Bridge of Earn artist, 84, has been capturing attention with his large city centre murals that have got him in trouble with Perth and Kinross Council.

But this only scratches the surface of a fascinating life involving rebellion and failure at school, working as a labourer, being stuck for a week in a perishingly-cold ship near Finland while serving for the navy, hobnobbing with celebrities as a PR officer, and being approached by the descendants of Andrew Carnegie during a remarkable career in which Ian made a fortune from trading art, antiques and numberplates.

As well as for what he has done, Ian is interesting for what he thinks. He is vehemently anti-monarchist, believes bankers are “gangsters and crooks”, says he would rather go to prison than buy a TV licence and has critical views on Perth and Kinross Council.

His story is in the following sections:

- Notorious estate and corporal punishment

- Labouring, navy and national service ‘turning point’

- Working with The Beatles

- Fine art and antiques fortune

- Numberplates, diamonds, silver and property

- Mural run-ins with the council

- Against the monarchy and the TV licence

- Health and mortality.

Notorious estate and corporal punishment

Whether through genes, upbringing or both, Ian’s generation of Imries have excellent staying power.

Ian is one of six siblings who are still going strong. They are: Doreen, 90; Jimmy, 88; Robert, 86; Ian, 84; Brian, 82; and Ellen, 79.

For the older members of the group, this is despite (or because of?) a basic upbringing in Perth’s Hunters Crescent, which later fell into decline and was renovated and rechristened as Fairfield.

Ian spent his first nine years – coinciding with the Second World War – at what would become one of Perth’s most notorious addresses.

“They were shifting people out of the slums and new-build tenement blocks,” he recalls.

“It was very basic. We didn’t have chicken or turkey. The diet was predominantly potatoes and soup.

“If you were lucky you might get a ham bone from the butcher and there might be some meat left on it.

“Nobody had bank accounts, cars, telephones, nothing. You just worked Friday to Friday to get a wage. That was it.”

‘He was quite a disciplinarian’

As with many people of his age, the war prevented Ian from seeing much of his father during his early years.

Robert was part of The Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) battalion and had stints in northern Africa, Monte Casino in Italy and South Africa. He was also evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940.

“I remember him coming back from the war, sitting by the fire and desert sand coming out of his kit bag,” Ian recalls.

“He was a typical Scot. He wasn’t very touchy feely and was quite a disciplinarian.”

When Robert returned from war in 1947 he moved the family to Muirton and embarked on a career in telecoms while his wife Ellen was a housewife.

‘You could get the belt for anything’

Ian has some harrowing memories of punishments meted out by teachers at Northern District Primary School (later Balhousie Primary School).

In the 1940s corporal punishment was a painful way of life for many pupils and Ian “got hit with the strap many times”.

Reflecting on one of the more notorious teachers, Ian asserts: “He would have been in jail these days.

“He was a very, very hard disciplinarian. The kids were terrified of him. The girls used to cry in class.

“You could get the belt for anything. It was a double-hander belt. It was abuse.”

‘I left school with no qualifications’

This was also the era in which passing or failing the eleven-plus exam would determine a pupil’s secondary schooling.

Ian ‘sat’ his exam, but did little else.

“I didn’t fill it in,” he says. “I just put my name at the top, and that was it. I was destined to go to the secondary school with the lowest denominator.

“I ended up in the lowest class of the high school. I left school when I was 14 with no qualifications.”

Labouring, navy and national service ‘turning point’

On his 15th birthday, Ian began working as a plumber for a company called Millers.

“Plumbing was different back then,” he says. “Nothing was ready-made. We had to use a wheel cart.”

I was picked up by police, taken to hospital, had my stomach pumped and ended up in the same cell that I had cleaned.”

One task that stands out was cleaning the drain of a cell at Perth Police Station, because he ended up in the very same place a week later, on Hogmanay, after drinking a bottle of whisky.

Ian says: “I was picked up by police, taken to hospital, had my stomach pumped and ended up in the same cell that I had cleaned.”

He tired of plumbing and did not complete his apprenticeship, moving on to general labouring, “digging ditches, manual work, salmon fishing on the Tay… I did anything I could,” he says.

“I used to go to contractor offices at 6am every morning to try to get work.”

‘We were stuck in the ice for a week’

When he was 17 Ian joined the Merchant Navy, training in Sharpness, Gloucestershire.

“My first ship was a passenger ship called the Orion which was talking emigrants to Australia,” says Ian, who also travelled to destinations such as Gibraltar, Sri Lanka and Saudi Arabia over two-and-a-half years.

He also had the misfortune to be on a ship from Grangemouth bound for Finland in December.

“It was quite an old ship that was built during the war and wasn’t the best accommodation,” Ian says.

“You never washed and there were no showers – you had to use a bucket.

“We went to Helsinki and the sea froze over so we were stuck in the ice for a week until an ice breaker came back to rescue us.

“It was absolutely freezing. We had no protective clothing and the whole ship was covered in ice.”

‘I had only ever had a pick and shovel’

Ian says his life changed after being called up for national service aged 19.

After his basic training at Aldershot he excelled in an IQ test and was given a job as an administrator at a petrol depot in Nienburg, Lower Saxony, Germany.

“There must have been something they saw,” he says. “Until then I had only ever had a pick and shovel.”

Two years on he returned to labouring but his time in Germany spurred him on to enrol at Dundee’s Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design.

“One day you are working on a building site, the next you are in the rarefied atmosphere of an art college,” Ian says.

“All of the students were middle-class professionals, so when it came to the holidays they would be abroad skiing while I would be on a building site because I needed the money.

“But I always think outside the box. At college I won three bursaries.

“In my final year I was teaching drawing so I had gone from a building site in 1960 to teaching in 1963. That’s quite a good shift.”

Working with The Beatles

Post-college, he worked for DC Thomson in Meadowside, Dundee, creating artwork for Jackie magazine.

Ian says he was then headhunted by former Dundee printer Valentine and Sons, for whom he worked as the art director and public relations officer.

He was involved in Mary Hopkin‘s 1969 album Post Card, as Valentines was Scotland’s leading manufacturer of picture postcards. Former Beatle Paul McCartney produced the album and released it under the Apple Records label.

“I worked with The Beatles and I met Jimi Hendrix when Paul and Linda McCartney were showing him around.

“I also went to New York a few times for work.”

Fine art and antiques fortune

In the early 1970s Ian decided to become a dealer of antiques and fine art so created his own company, Imrie Fine Art, which he set up in Back Street.

“People ask me how I learnt about fine art or antiques,” he says. “My answer is, ‘lose money and make mistakes’.

“It is the basic business model of buying for cheap and selling for more. And hopefully in the transition you make a profit. You sometimes make a loss, but not often.”

Ian reached the top end of the industry, attracting buyers from the likes of New York City, Los Angeles and South Africa, on the back of a number of shrewd and inspired trades.

“The ability to see what makes it good is the secret. You can’t learn from books. In the 50 years I have been doing it I have had guys with degrees in fine art couldn’t make it work.

“It is an instinctive, streetwise thing. I was called Mr 10 per cent: when I bought something for £50 and someone offered me £55 I would sell it. I was in volume then.”

Bought for £2k, sold for £58k

The real money is in the low-quantity, big-ticket items, though.

One such success related to a desk designed by Thomas Chippendale in 1750, remade by Gillows of Lancaster in 1845.

Ian purchased it in the 1980s from an auction house in Fife for £2,000 and sold on for £58,000.

“I saw this desk with the draws and a blanket over it,” he recalls. “All I could see was the gable end. I said to the auctioneer ‘that’s a nice thing’.

“She replied that it was going to London. I asked if I could look at it and she said it was going to cost £150 to send it to London. I said ‘why are you going to send it to London? I can buy it off you.’

“She said, ‘no no, we can’t do that’. I said, ‘what do you want for it?’ They said it would be £2,000 so I said I would take it.

“Fine art is a small community and once I had bought it I had phone calls from people wanting to buy it.

“I put it through auction a couple of months later and it ended up in Switzerland.

“That was an amazing buy.”

‘Who do you think I am, Andrew Carnegie?’

A more recent acquisition was a painting by Walter Launt Palmer, known as the first impressionist, which Ian purchased from the descendants of Dunfermline-born steel magnate Andrew Carnegie.

Ian bought the item for £25,000 and sold it for £85,000.

“What was interesting about being approached by his descendants is that when growing up in a working-class environment in Perth you would ask for sixpence, the response would be ‘who do you think I am, Andrew Carnegie?’

“This is because he was the wealthiest man in the world and there I am, all these years later, holding a painting that he bought in New York in 1915 for around 290 dollars.

“It was hanging up in his house but I owned it. My mother would not have believed it.

“To go from that really basic working-class situation to where I am all these years later is absolutely incredible.”

Number plates, diamonds, silver and property

Number plates have also been a lucrative investment for Ian.

His Rolls-Royce Mini Goodwood is in itself super-rare – only 1,000 were ever made – and its 1903 numberplate, M53, was on only the 53rd car ever registered in Manchester.

The mark was once owned by Lord Kinnaird, who took his old car into the garage “and didn’t know they had transferred his number plate,” Ian claims.

“So I got a phone call from a salesman about buying a number plate. He said it would cost £2,000.

“I thought it was rather naughty of them, not telling Lord Kinnaird that they had done that.”

But he still paid the money for a number plate that is now worth £60,000. The number plate on his other Rolls-Royce, RR80, is worth £30,000.

The GS1 number plate is one that got away, though.

“I got a phone call from someone asking if I want to buy it for £50,000,” Ian says.

“G means nothing to me, it is not my initials, so I didn’t do it. So they sent it to auction and it went for £250,000. You just don’t know with number plates – they are big business.”

‘If I cashed everything in I could be a billionaire’

Ian’s home in Bridge of Earn would now be worth 20 times the £24,000 he paid for it, in cash, in 1980.

His two-storey building in Back Street, built in 1987 as an antiques showroom, is now being rented out.

“I designed it in such a way that when I retired it could be converted into five flats,” Ian says.

“If I cashed everything in I could be a billionaire. I own an acre of land opposite my house and it has gone on the market.

“I’ve got investments, I’ve got diamonds, silver, number plates. This house is worth a few bob.”

‘Bankers are gangsters and crooks’

Despite his accumulated wealth, Ian remains an active trader.

“I recently bought a lovely carriage clock for £1,300 and I sold it for £1,400 so I made £100 profit,” he says.

“If £1,300 was in the bank it wouldn’t make a penny. Bankers are gangsters and crooks.

“At one time during my career I would go to the bank and the teller would say ‘Good morning, Mr Imrie, how are you and how is your wife?’

“Now they don’t even know who you are. It just doesn’t exist. It has become so impersonal. You can do banking online and all this rubbish. I just shake my head.”

Mural run-ins with the council

The money has given Ian the freedom to pursue art on a totally voluntary basis.

He describes himself as a flexible “visual” painter who can draw “anything”, whether portraits, landscapes or bigger compositions.

“I don’t advertise or exhibit. I have sold to different clients but I am not bothered because I don’t have to do it financially.

“I don’t need the money so if someone sees my stuff and wants to buy then I may sell. I don’t put my pictures out there. That’s the freedom.”

‘They never bothered with that’

However, Ian very much does seek to promote his murals.

His designs are usually painted on four separate panels made of laminated aluminium. It’s bomb-proof. They are then screwed on to the wall “rapidly and subversively”.

Ian’s first mural was in 2018 to mark the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War, a conflict in which his grandfather John was a casualty.

“I put them on the wall overnight opposite Marks and Spencer in Perth,” he says.

“That was the first one. There was no response from the council, probably because of the subject matter. They never bothered with that.”

‘They just don’t understand it’

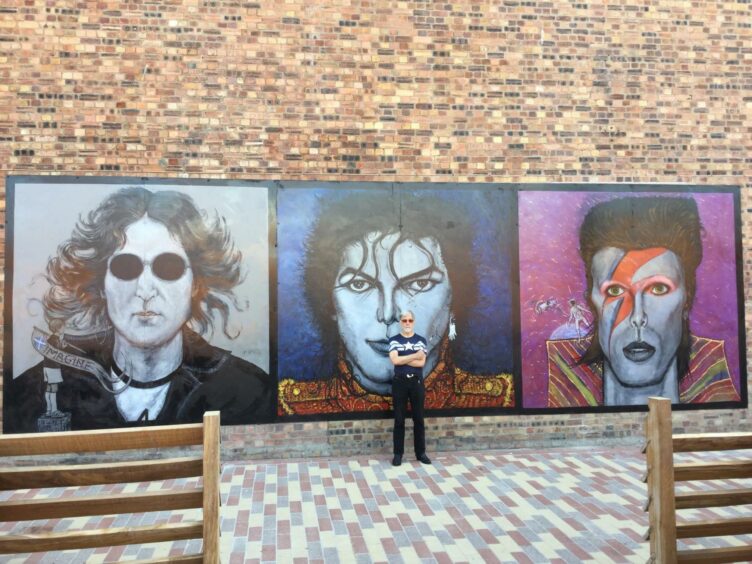

Also that year, Ian’s 10ft-tall portraits depicting singers John Lennon, Michael Jackson and David Bowie was installed on Mill Street.

This time, Perth and Kinross Council ordered for these to be removed. A separate mural of Jimi Hendrix was mounted on the exterior wall of the Giraffe Cafe, also on Mill Street.

Again in 2018, he plastered his painting of a Scottish terrier holding a heart-shaped saltire balloon on the back of Perth Theatre.

Bosses at Horsecross Arts, the creative organisation behind the theatre, worked with the council to have the piece removed.

He also painted a 40ft memorial to war veterans at Perth Prison, where he took art classes in the 1970s.

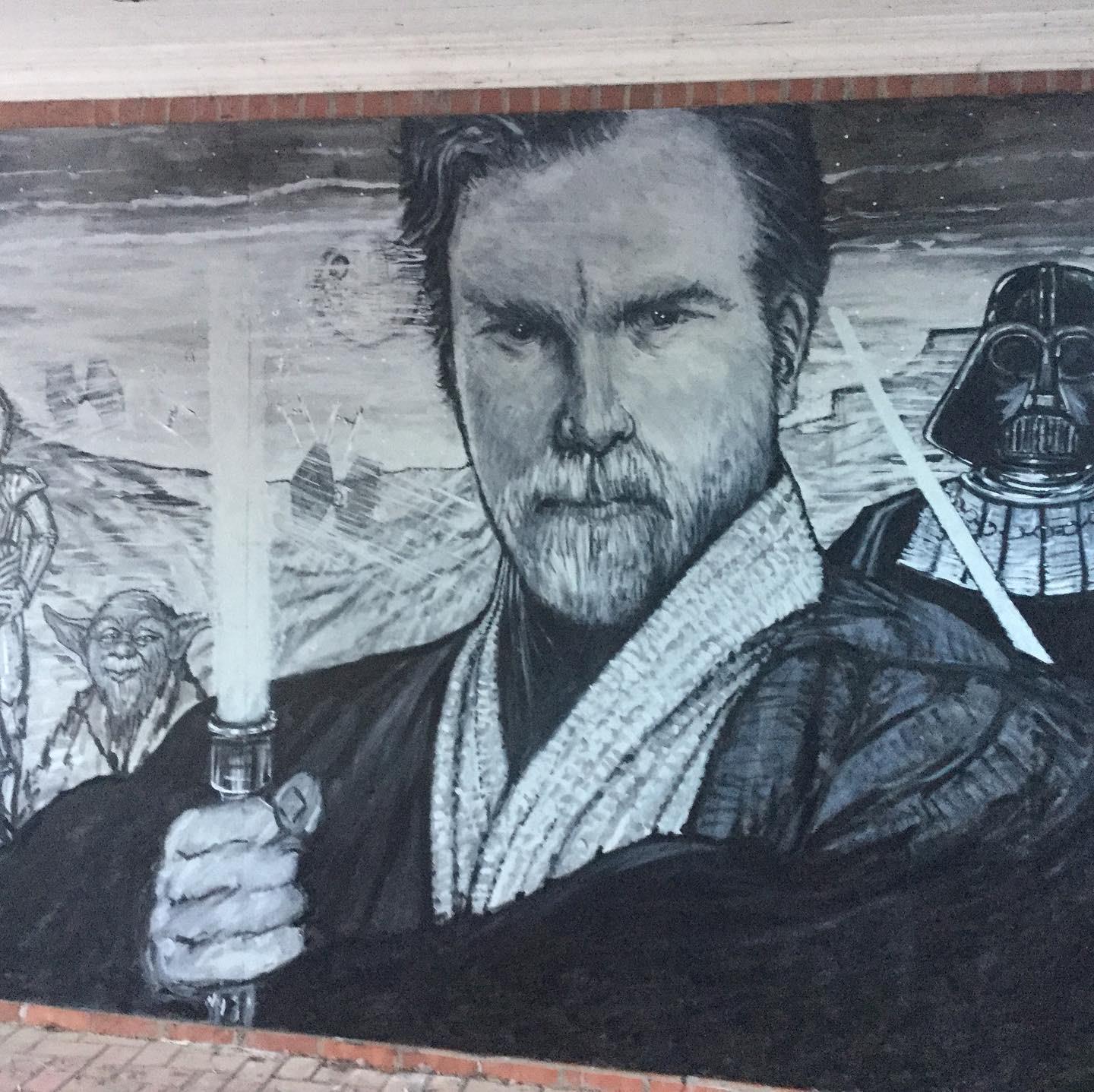

In 2021 a mural honouring Star Wars actor Ewan McGregor was unveiled in the actor’s home town of Crieff.

Earlier this year Ian was given the go-ahead to show off a range of his work on St Paul’s Church.

“Street art is an art form, it is ground level coming up,” Ian says.

“If you tell the council you are going to put up some street art that defeats the purpose of the whole thing. It is a statement. People who connect with street art would never go near an art gallery.

“It’s the wow factor. You are driving your car and suddenly you see something and ask ‘where did that come from?’ That’s the essence of it.

“The sad thing about local authorities and planning departments is that they just don’t understand it and can’t get their head around it.”

‘Perth is a lovely city but dull’

The council says that its “planning and regulatory role is purely about ensuring any impacts on a property or the surrounding area were considered in the public interest.”

But Ian believes other cities let a lot more go.

“If you go to Glasgow and Dundee it is full of street art,” he says. “They don’t have a negative attitude. They say they like it so let’s do something with it.

“In Stobswell they want me to do a mural this year. That is the attitude. But in Perth they say no.

“That attitude is why a German dealer friend of mine says Perth is a lovely city but dull.”

Against the monarchy and the TV Licence

Of intrigue is why Ian only decided to install murals as an octogenarian.

“I have always been outside the box, that’s my character,” he says.

“I have it in me. I am very streetwise and I don’t tend to go along with the recognised line.

“Why did an 84-year-old guy born in a council estate become such an anti-monarchist? Where did that come from?

“I used to say to my teachers that the history we were taught about Scotland was the history of England, really. It was all brainwashing.

“Back then, if you made an adverse comment about a member of the royal family they would hang me from the nearest lamppost. The indoctrination was so intense.”

‘Is this North Korea?’

His rebellious, anti-establishment side is additionally apparent in his views on the TV licence, which is now only free for over 75s on pension credit.

“I don’t buy a TV licence, I don’t acknowledge the letters,” says Ian, who also refuses to acknowledge someone who has been knighted with a ‘Sir’.

“I got a letter last week saying ‘You have been watching iPlayer’ and I’m thinking, ‘Is this North Korea, how do they know I am watching that?’

“I can afford a licence. Television is a window to the world for people who are not well off so I am quite prepared to go to jail over that.

“That is typical me – I am very principled.”

Health and mortality

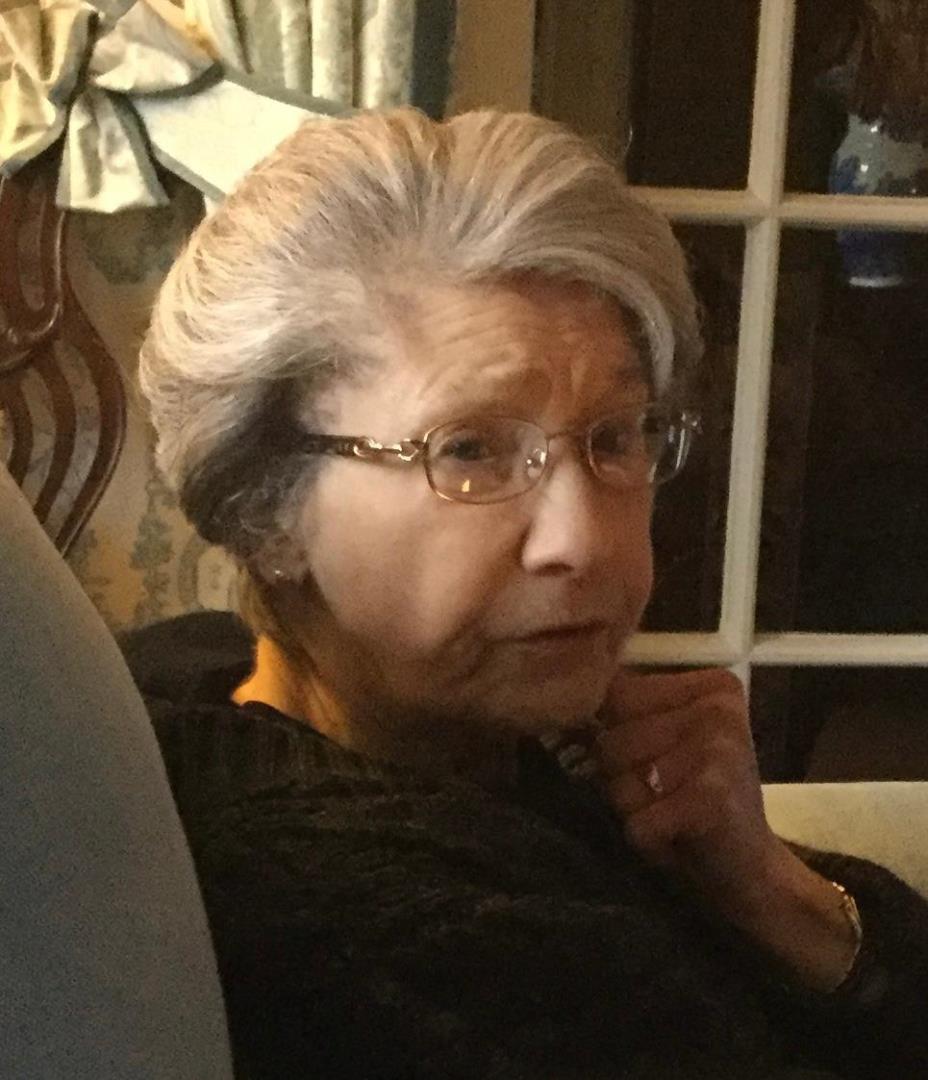

For the past decade, Ian has been the carer for his wife Margaret, 80, who grew up on a farm in Bankfoot.

The pair met in 1960 just after Ian had completed national service.

“She was a very small girl, a bit of a rock chick,” Ian says. “We courted for six years before marriage.

“When I was in college she would give me £1 a week from her wages as a retail assistant to help me.”

Margaret had a stroke 10 years ago and is partially sighted. She has also fought tongue cancer.

‘I would have been dead by now’

Ian has also had a significant health challenge of his own. Two years ago he needed a major operation on an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

In April 2020, during the Covid lockdown, surgeons made a 15-inch incision to prevent the bulge from increasing.

“After the operation, for a few days I was out of it, I was hallucinating,” he recalls. “It was a very strange experience.

“At one point I didn’t know what time it was, what day it was. I thought all the staff in the ward were Chinese and I was worried because I couldn’t speak Cantonese or Mandarin!”

Ian has his own personal gym at home and works out for 30 minutes every day to maintain the same weight, 11st 7Ib, that he has been since he was 19 years old.

“The surgeon said I was so fit, otherwise they wouldn’t have bothered with the operation,” Ian says.

“And they said that if they hadn’t have bothered I would have been dead by now.

“If it wasn’t for being so healthy I would be dead.”

‘I will leave my body to science’

Given this near miss, it is no surprise that Ian is contemplative of his own mortality.

“Spike Milligan said that he didn’t mind dying but just that he didn’t want to be there when it happened.

“We are all going to die regardless of how many sit-ups and press-ups we do.

“Psychologically, when you get to your middle 80s you say to yourself, ‘have I got 10 years?’

“I remember buying stuff from a 90-year-old woman in Fife. She told me the older you get, the faster time goes.

“I am aware of dying and I will leave my body to science.

“People from Dundee university will look at me and say, ‘He was pretty good, eh?”

Conversation