The distinguished and sometimes tragic story of Black Watch soldiers in the 20th century is being explored in the new official authoritative history of Scotland’s oldest Highland regiment. Michael Alexander spoke to the author.

It is the regiment with the strongest links to Courier Country, and in recent months there has been talk of returning The Black Watch – or 3 Scots – to Leuchars, at the heart of its traditional Tayside and Fife recruiting ground, as the base expands.

It’s the history of the famous regiment in the 20th century and beyond, however, that forms the basis of a new book by British author and military historian Victoria Schofield.

The Black Watch: Fighting in the Frontline, 1899-2006, looks at the heroic and inspiring story of the regiment which saw the soldiers distinguish themselves in theatres of war across the world – but also suffer more than its fair share of losses.

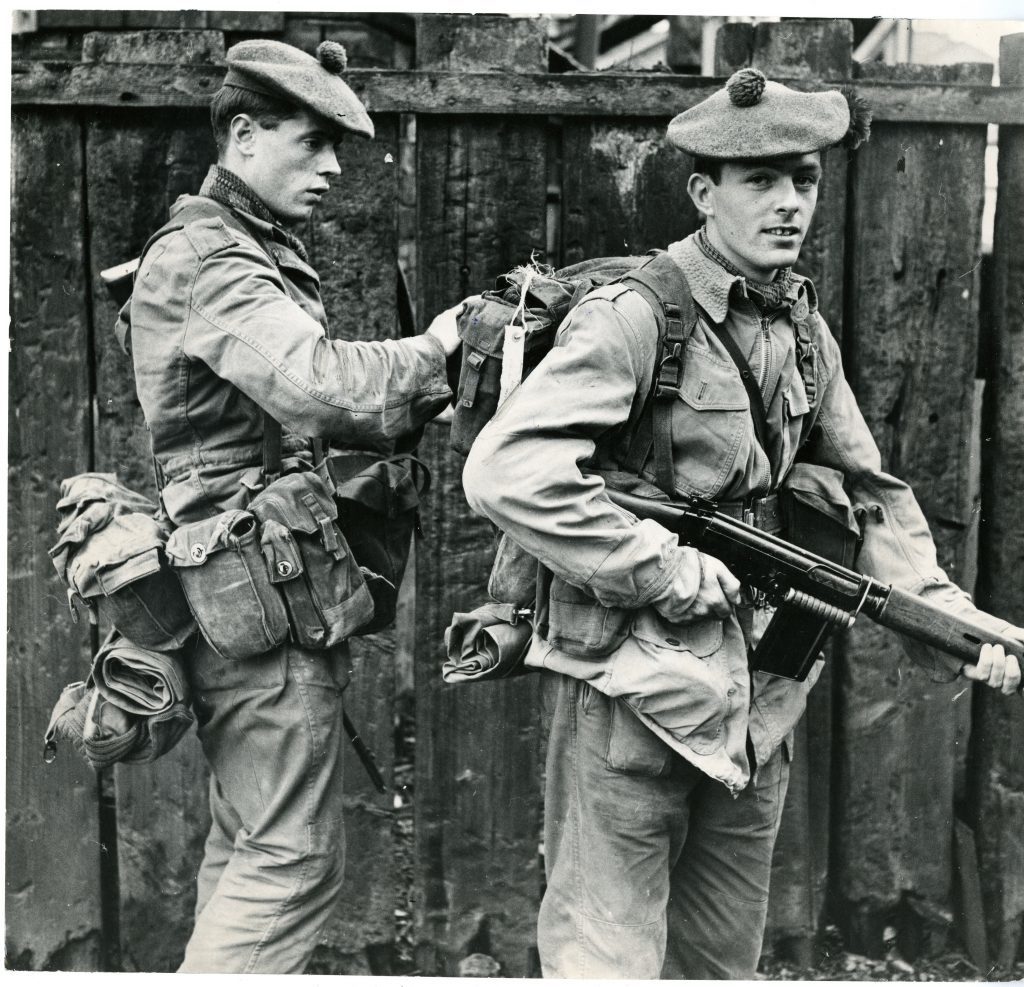

Originally raised to keep ‘watch’ over the Anglo-Scottish border, the Black Watch formed into a regiment in 1739 and, named after the dark tartan of its soldiers’ kilts, has fought in almost every major British conflict between 1745 and the present day.

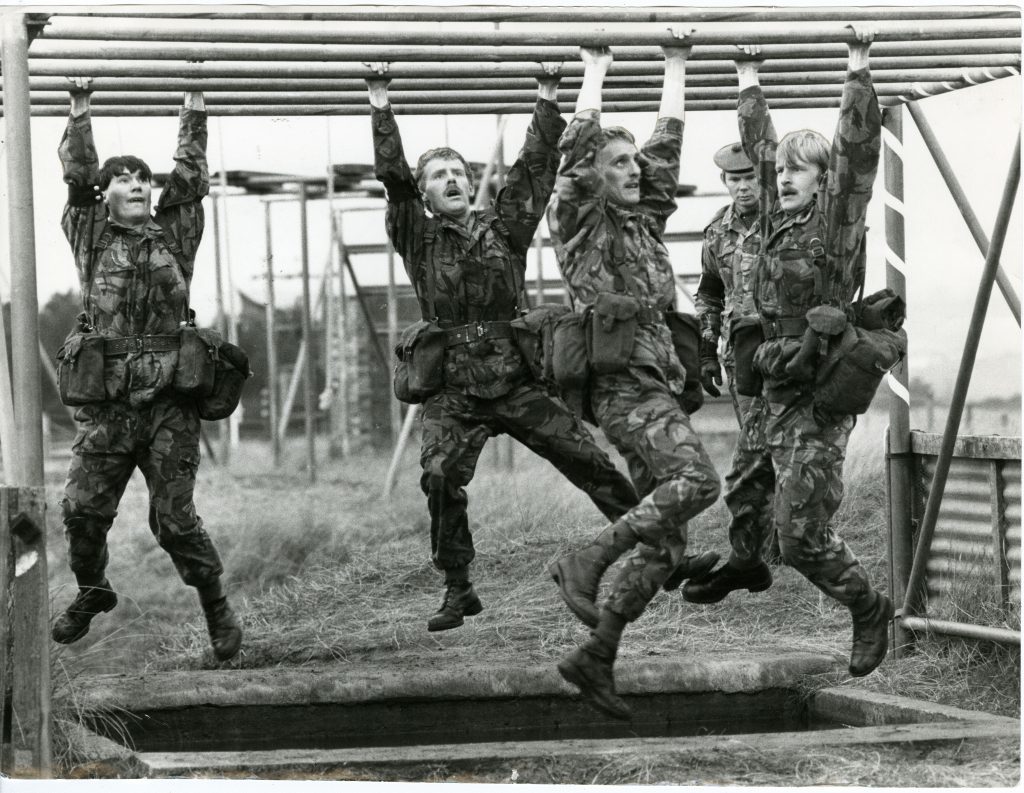

Victoria, who has written for The Sunday Telegraph, The Times and The Independent, recounts the modern history of the Black Watch from the Boer War onwards, tracing its service in two world wars, the Korean War, Northern Ireland, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Drawing on diaries, letters and memoirs, but also on interviews with living veterans, she weaves the multiple strands of the story into an epic narrative of a heroic body of officers and men over a century of history.

Speaking to The Courier from London, the Oxford University history graduate explained that it was her service family background and interest in Pakistan – the home of her close friend and former prime minister Benazir Bhutto – that got her involved in the Black Watch project.

“I have written a lot about Pakistan and India,” she said, “and I had completed a book on Kashmir in the 1990’s.

“One of the things that kept coming back to me was what we British did in the run up to India and Pakistan becoming independent 70 years ago.

“Instead of writing a dull old study on partition again, I thought I would write a biography about one of the key central figures who was around when a lot of these important decisions were taken.

“People had written on Mountbatten, but no one had really written properly on Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, who was of course Black Watch, and the Viceroy before Mountbatten.

“Literally at the time the Wavell book came out in 2006, the regiments were merged into the Royal Regiment of Scotland and not very long after, the Black Watch Museum trustees approached me because they wanted to have the regimental history written once and for all but from the more journalistic approach.”

Victoria spent months travelling to and from her “focal point” of the Black Watch Museum in Perth as well as Fort George.

In addition to researching letters and diaries, Victoria interviewed around 100 former Black Watch soldiers ranging from a 100-year-old Palestine veteran to more recent veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan.

The book, which gives an insight into the functioning of the regiment and the thoughts of officers and men serving within it, finishes with the Laying Up of the Colours in 2012, which consigned the Black Watch Colours to history.

Victoria describes the Black Watch identity as “hugely important” throughout the centuries.

As the oldest Highland regiment, she wasn’t surprised to find there was some upset within the Black Watch family when the merger was first proposed.

Yet inevitably “times had moved on” and the army itself had changed.

“The old and bold were very vociferous about the merger but ultimately the younger ones just wanted to be soldiers, so they just had to make the best of what they were being offered,” she said, noting that 3 Scots had been allowed to keep the Red Hackle.

“But what was interesting and has to be remembered is it wasn’t just the Black Watch marching through history. They were marching alongside other brigades. So it was the Scottish-ness as well as the individual identity of the regiment that was being talked about.”

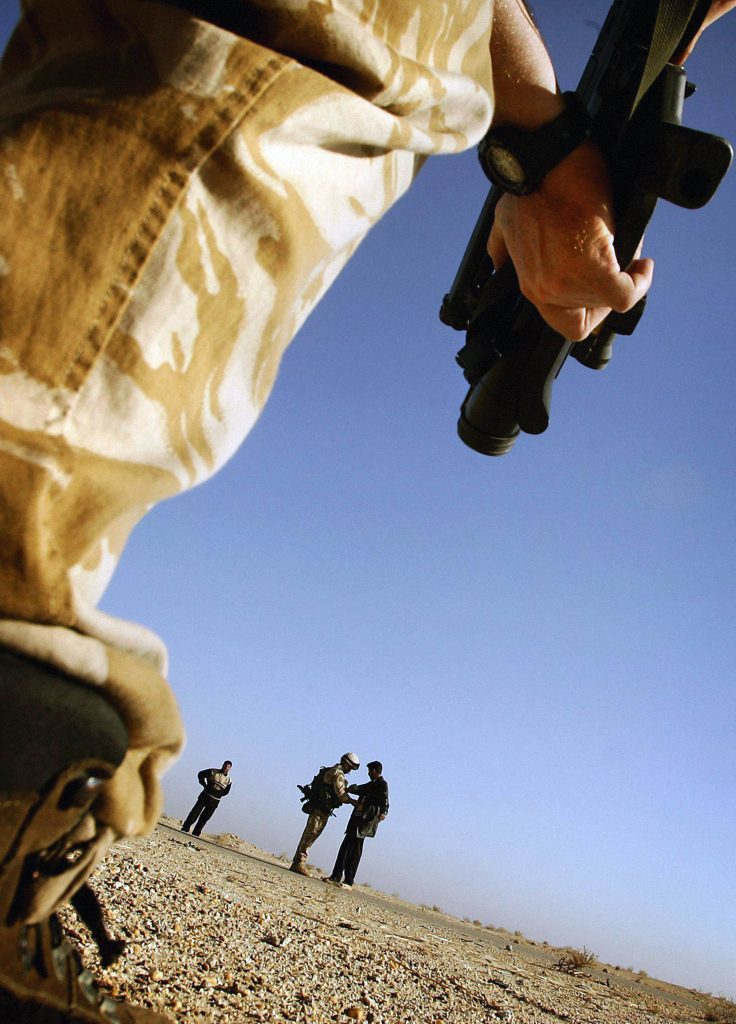

Victoria also interviewed veterans of the 2003/2004 Iraq War. And she was struck by the view amongst the younger soldiers that “a life is a life”.

She added: “The fact that these guys lost six guys in Iraq during two tours – 2003/2004 – meant as much to them as the thousands that were lost in World War One. It was a challenge to write that because you don’t want to belittle any loss of life. Off the top of my head, the official regimental figure for losses in World War One is 8,960. They say 50,000 passed through the ranks of which 20,000 were wounded.

“Particularly coming in these World War One commemoration years, that was a very emotional statistic to acknowledge.”