Perthshire author Jess Smith has struck another blow for Scottish Travellers by helping to produce the first dictionary of their language.

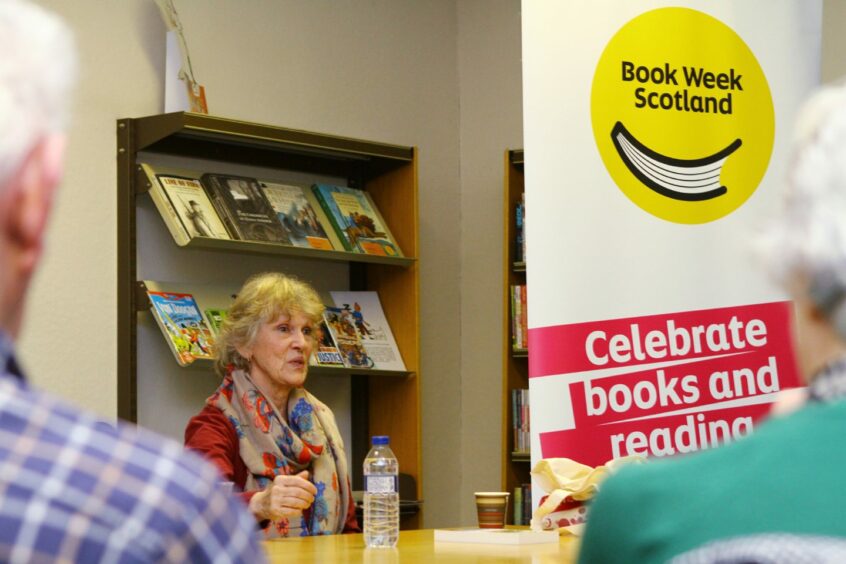

The 75-year-old great grandmother worked closely with the book’s creator and spoke at its launch at Edinburgh University.

The publication comes weeks after she received the British Empire Medal for services to the Scottish Traveller community.

Jess, whose own books have shone a light on the persecution that she and other Scottish Travellers faced, said it was a proud moment.

“What is a culture if it has no voice?,” she said.

“Now for the first time Scotland’s Travellers have theirs.”

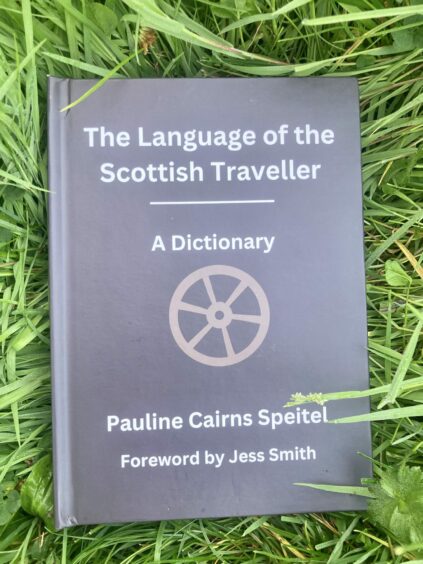

Jess said she hoped the book – The Language of the Scottish Traveller: A Dictionary – would help to break down some of the barriers of ignorance which divide Travellers from the wider community.

And in her foreword she describes how the language was a form of protection when she was growing up.

She writes: “When our parents saw a stranger approach, they would say, ‘bing avree’ (come here, and not be seen). And we knew to hide because that was what they were saying to us.

“It was their words of protection,” she adds.

“And when the stranger had left our parents would say, ‘nae paggering frae the gadji’ (this person means us no harm).”

Jess Smith’s journey from bus to BEM

Born into a travelling family, Jess Smith spent her childhood touring around Perthshire and Fife in a converted Bedford bus.

She and her husband Davie live in a cottage near Comrie, today. But her upbringing was dictated by the seasons, following the farm work and living a traditional Scottish Traveller lifestyle.

“Everybody loves you until they find out you live on a bus,” she laughed.

A born storyteller, she remembers her mother telling her “Away and talk to the nettles” when her incessant chatter became too much.

However, she did not start writing seriously until after the death of her father.

Charles Riley had written his own unpublished memoir. And Jess made a deathbed promise to him that she would tell the story of their culture on his behalf.

She joined a writers’ workshop in Crieff and had a poem – Scotia’s Bairn – published to mark the Millennium.

It was inspired by a memory of sitting on a bus in Kirkcaldy when another girl refused to take the seat next to her because she was a Traveller.

Jess went on to win critical acclaim for a series of books, including Jessie’s Journey and The Way of the Wanderer.

She is also in demand as a speaker and storyteller. She has visited schools, prisons and countless local halls as part of her efforts to celebrate the Scottish Travellers’ way of life.

Campaign work key to Jess Smith recognition

The BEM also recognises Jess’s work to have the Tinkers’ Heart in Argyll recognised as a scheduled monument.

The collection of stones in the shape of a heart was where Travellers held weddings, baptisms and blessings for the dead.

She launched a Scottish Parliament petition in 2014 and campaigned successfully to have it recognised by Historic Environment Scotland.

Jess said she was proud to accept the BEM on behalf of all Scottish Travellers.

“Our traditions have survived, despite all manner of hunting and hounding,” she said.

“So it means something when the top person opens up that closed door and says ‘we recognise you and your culture’.

“If the King wants to give me a wee medal I will take it for them, for all the Travellers,” she added.

“They’re the ones who matter.”

Dictionary documents vanishing language

Pauline Cairns Speitel, author of The Language of the Scottish Traveller: A Dictionary, said Jess provided the inspiration for the project.

She embarked on it after being sent a volume called The Scottish Traveller Dialects, which was co-compiled by Jess in 2002.

Pauline said many Scottish Traveller words could be traced far back into history.

She said some – such as gadgie and radge – are now in common usage.

But others are used far less often as more Scottish Travellers turn to the English vocabulary in order to be accepted by mainstream society.

The dictionary is also available online.

Conversation