As the Garry Bridge in Perthshire marks its 50th anniversary, Michael Alexander meets former workers who helped with its construction from 1967-69.

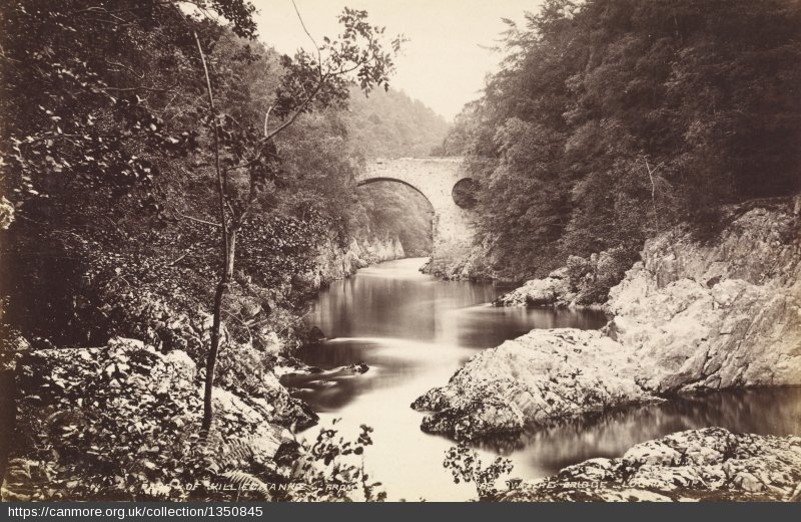

It is perhaps best known today as the bungee jump location near the famous site of the Battle of Killiecrankie.

But former workers who helped build the Garry Bridge, 40 metres above the River Garry in Highland Perthshire, have been reminiscing about the trials and tribulations that went into its construction ahead of its opening 50 years ago this spring.

From a fundamental design miscalculation that led to a six-week delay in construction to antiquated pre-war machinery breakdowns – and a less stringent than today health and safety culture – several former workers who still live in the area have told The Courier how they still take pride in the bridge five decades on – but have never been tempted to try a bungee jump!

Pitlochry man Ian Hendry, 82, who was brought up in nearby Ennochdu was 30-years-old when he started work in 1967 with the main contractor AM Carmichael as a construction fitter, responsible for the maintenance of up to 48 units of machinery.

Having done his National Service in the RAF, he had previously been a foreman working on the nuclear submarine base at Coulport on the west coast before family reasons brought the father- of-four back to Perthshire.

With much of the “well worn” often pre-war equipment left over from the construction of dams, tunnels and aqueducts on the Errochty hydro scheme, his abiding memory of the Garry project was regular breakdown of engines, cranes and generators and the “horrendous cold” in the winter of 1967/68.

He also has memories of the “characters” amongst the workforce – including a few so-called “hard men” and a number of Irish “relics” who had been working on dams. Most of the men were bussed in from Aberfeldy each day.

However, he never lost sight of why the new bridge linking what was then the old A9 with the Queen’s View and Rannoch Moor to the west was so strategically and economically important.

“What the bridge did was it opened up the road to Rannoch in the west at its most hazardous point from Pitlochry to Rannoch,” said Ian, pointing out where concrete for the piers had been poured on site.

“Before that there had been numerous bad accidents in the gorge area.

“On the old road going to Rannoch, slightly up river where the footbridge is now, there used to be an old stone bridge that had been there for centuries which had a really tight hairpin at right angles to the river with no more than a 2’3” parapet.

“When I was still at school – I think it was around 1949 – a couple were on bikes and she hit the parapet and went over, falling about 80 feet. She landed in the ‘black hole’ – supposedly where a stagecoach had once gone down with loss of lives. It had whirlpools and whatnot.

“It was a Polish soldier recuperating, fishing at the time, who jumped in and saved her life.”

Ian said the Royal Engineers were brought in to replace the stone bridge with a prefabricated bailey bridge – predominately to facilitate the transport of equipment being used in the hydro schemes.

However, while the new modern Garry Bridge would open up the area considerably as general traffic grew, its construction also brought a number of technical challenges – notably the discovery in the early stages that different teams were using different data sets, meaning that the construction height measurements were initially wrong leading to a delay until it was sorted out.

“If you stand on the bridge today it’s very dramatic with amazing views up and down the valley,” he said.

“But it’s a very tricky environment there because you are having to cross the railway line and the river. It was very challenging for everybody involved – especially with the rock formations and extreme gradients at both sides where a lot of blasting had to take place. We also had to put in a lot of pile into the back of the railway to stop it subsiding.”

Ian left the Garry at the end of 1968 – several months before it opened. He went on co-run a guest house in Oban and later bought the Rosemount Hotel in Pitlochry where he became a weel kent face.

However, when he thinks back, he still regards the Garry Bridge as the “top of the endeavours” he was ever involved with.

It’s a view shared by Blair Atholl man Mike Shanto, now 74, who took over from Ian as a 24-year-old foreman fitter.

With his father having worked for AM Carmichael on the Garry hydro intake, he enjoyed the work and was a fast learner – taking books home in his own time to overcome the fact the nearest he’d seen to a diesel engine previously was a “wee paraffin tractor”.

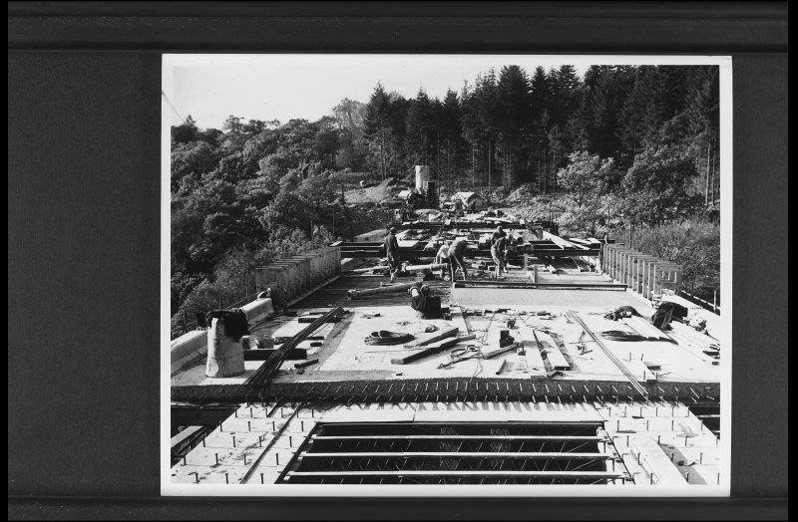

A keen photographer who took photos of th bridge’s progress, he had particular issues maintaining the compressor that pumped concrete through pipes. It was a giant piece of equipment on huge iron wheels and was “murder” because it was always leaking.

However, he finds it amazing that no one was ever seriously injured or killed.

“The safety issues were horrendous – bloody hairy!” said Mike, who learned to be a time served mechanic at his local Blair Atholl garage and went on to work on the M8/M9 and offshore after the Garry project ended – later becoming a painter and decorator.

“I don’t know how anyone was never killed. There was no handrail or nothing during construction. I was allowed to walk out on the beams. All they had below -and I had to walk out each day to check it was still there – was a wee rowing boat.

“And I also had to check the ropes on the cranes. Given the height, what was the point of the boat? No one would have survived if they’d fallen. You’d never get away with it now!”

Another worker on the bridge was Bill Stewart, 79, of Aberfeldy.

Born in Kilry north of Alyth, he got a job rock drilling and blasting for AM Carmichael having previously worked in England and on rock tunnels on the Cruachan power station at Dalmally.

“We started off making the road above the old A9 to elevate the road up to the height the bridge was going to be,” he said.

“The old A9 down below it was on traffic lights. That was the main artery to the north in those days and it wasn’t nearly so busy as it is now.

“On both sides all the rock had to be excavated. Three quarter of the way down on both sides of the bank where the pillars came up – that large area had to be cleared of overburden and the rock had to be hand drilled and blasted and put into skips.

“There were not many diggers in those days. It was a bloody hard job and a bloody cold one in the winter.”

Bill, who has had operations on his back and now walks with a stick, also talks of different work conditions at the time and believes the long term health implications affect him to this day.

He added: “We were standing holding on to the rock drilling machines for nine/10 hours a day.

“Now you are only allowed to hold on to one for half an hour for health and safety reasons.

“I’m deaf and I’ve got industrial vibratory white finger. Because I went on to be self-employed for the last 35 years – the authorities said it could have happened then. But it happened all those years ago in the 1960s with me. I know it.”

Bill went on to work on the construction of a dam at Cawdor and then the M8 motorway.

However, having enjoyed walks by the Tummel over the years, crossing the bridge always reminds him of the characters of old – many of whom have since passed away.

In particular, he’s reminded of the Irish gangers who ensured that workers kept “slaving away”.

“You got your back lifted – they were watching you all day,” he said.

“You had to keep slaving away – not like nowadays with the young lads with their backs against the wall with both thumbs on their bloody phones texting one another continually.

“That would never have been allowed. When they started the men off at the labour exchange in Pitlochry – the broo – they were on a fortnight’s trial, under surveillance. I told them –because I’d been working on public works before: ‘Always be doing something – if you haven’t got a job, pick up a brush and sweep something because folk are watching you!’

“Because a lot of the young lads got in the group and played about. They got sent back to Pitlochry after a fortnight. Just useless…”

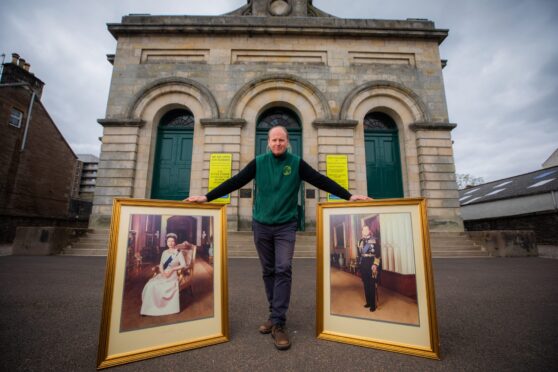

Highland ward SNP councillor Mike Williamson, 58, whose ward includes Pitlochry, has been researching the history of the bridge which cost £220,000 to build (around £4 million in today’s money).

He’s heard anecdotal stories of a man crossing the girders at night and the day blasted rocks landed in a local boy’s paddling pool just minutes after he went in for his tea.

However, even when it opened it was not without it’s difficulties.

“This was the first box girder bridge in Perth and Kinross,” he said, noting that the church even donated a brass plaque. “It predated the Friarton.

“But it had to close shortly after because of accidents in Merthyr Tydfil and Melbourne where they collapsed.

“The bridge had to be strengthened in 1970s. It was nothing to do with the construction. It was a design flaw.”

What impresses him most today is that as well as being a functional bridge, it doubles as a viewing platform and a bungee jump destination.

“The guys who helped build it have an awful lot to be proud of,” he added.