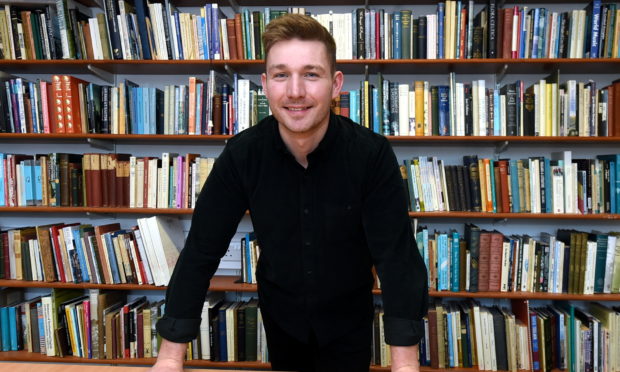

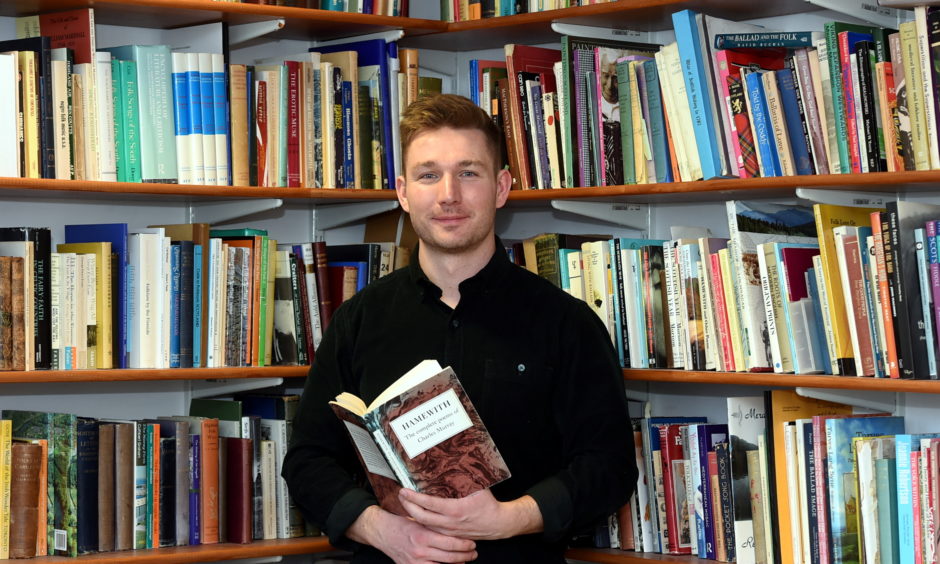

Michael Alexander speaks to Angus writer Alistair Heather who is on a mission to reassert the vitality of Scots as a native language.

He describes Scots as the “partially submerged language of a partially submerged nation”.

But when Angus-raised Scots language expert Alistair Heather looks at how the “mither tongue” is re-emerging alongside Scottish history, literature and music, he is confident that decades of Scots language “oppression” by educators, politicians and broadcasters is finally turning a corner.

Alistair’s love affair with Scots dates back to his days at Newbigging Primary, near Monifieth, when the school won the prize for the best Scots language school in Scotland.

He had a “remarkable” teacher called Mr Henderson who taught pupils the bagpipes, how to pluck pheasants and gut fish. The teacher also used to get old retired folk in from the village to teach pupils the local dialect.

Going on to Carnoustie High, Alistair spent seven years overseas before studying history with Gaelic at Aberdeen University. His dissertation was on use of Scots in Angus by the Jacobites.

Now, having spent the last two years working with Aberdeen University to promote their research around Scots language, the 30-year-old is fronting a BBC Scotland documentary Rebel Tongue where he sets out on a mission to “reclaim” Scots after decades of folk being “mocked” or “assumed daft” for speaking their native language.

“When I first started working in Dundee when I was 17 at a call centre, folk would be telling each other ‘dinnae speak oary!’,” he tells The Courier.

“That was a working class environment where everybody came fae working class Dundee or rural Angus, and Scots should have been the first language of the community.

“But we were self-policing because we had been telt oor language isnae right, and when you take that awa’ fae folk, you limit their ability to express themselves and you delegitimise their culture.

“What you are basically saying is ‘you are not speaking right, the language you learned from your family isnae right so your family are daft as well and all the culture in that language is less legitimate than the dominant Anglo-centric culture’.

“Whereas what we should have been celebrating is the fact we are bilingual.

“Most working class folk in Dundee speak Scots and they speak English. That’s a skill we should be proud of!”

Alistair remembers his grandparents saying they would have got the belt at school and been “laughed at” if they spoke Scots.

Yet Scots was once the tongue of most lowland Scots, of the Royal Court and great poetry.

Alistair claims that the demise of the language can be traced to the departure to London of Scotland’s King James VI, to the received pronunciation of the BBC, and to generations of teachers insisting their pupils speak “proper English”.

Somehow, the Scots language survived all that. It is now one of Scotland’s three official languages, with English and Gaelic.

The 2011 census indicated that one and a half million people claimed to speak Scots, making it the largest minority language in Britain.

But still it is ignored, he says. Scots receives only a fraction of the government money spent on Gaelic.

“The point we make about Gaelic is that Gaelic suffered many of the same prejudices as Scots does today, 70 or 80 years ago,” he adds.

“Folk who stayed in Sutherland and spoke Gaelic didn’t really ken that folk who stayed in Argyll spoke the same Gaelic as them, and none of them thought the people of Lewis spoke Gaelic.

“It wasn’t until the BBC started broadcasting that all those Gaelic speakers realised they are part of a language community.

“Dundee Scots speakers don’t really realise they are speaking the same language as a Borders farmer or somebody that lives in Govan or someone in Peterheid.

“One thing that we should really take from the Gaelic movement is helping different Scots speakers of different dialects to become more aware that they are speaking a shared language. That’s one of the aims of this.”

In Rebel Tongue, Alistair tells the history of the language and argues that Scots is fighting back after decades of ignorance and oppression.

The programme starts at Tannadice Park when he speaks to fans attending a Dundee United v Dunfermline game about the use of Dundee Scots.

He also travels to Buckie in Moray, to Aberdeen, to Hawick in the Borders and to Edinburgh and Glasgow.

He explores how there’s a “grassroots activist renaissance” happening round the different dialects and explores the history of what was Scotland’s national tongue for centuries.

“There was always a perception since the 1900s that if you are speaking oary, it’s because you haven’t been to school as much,” he adds.

“Yet that perception is changing. I think there’s more confidence around Dundee Scots now.

“When you are in Fife and Angus you will also see mair folk with diverse backgrounds using Scots a bit more confidently. It’s never been as mixed up with class as in Dundee.”

Alistair also highlights an Abertay University study which examined the psychological side of how Scots works in the brain.

He adds: “The study showed if you speak two different dialects it’s quite hard for your brain to jump between the two dialects as they are all stored in one part of the brain, whereas with two languages the language is stored separately.

“The study showed that Scots and English are stored in different parts of the brain, so your mind treats it as a language. That’s quite a nice thing to come out of Dundee!”

*Rebel Tongue is on the BBC Scotland channel from 10pm – 11pm on Tuesday April 28.