With St Andrews Day on November 30, Michael Alexander explores the international reach of Saint Andrew that goes well beyond the shores of the Fife town that bears his name:

Pick your way along the slippery rocks from St Andrews castle towards the harbour, and in the face of the cliff overhanging the shore around 150 yards south-east of the Castle Sands, the much eroded remains of Lady Buchan’s Cave clings to the rock face above.

According to local folklore, it’s named after a local woman Lady Buchan, who, a century or two ago, is said to have used a once larger artificially enlarged cave for tea parties and picnics with two ornamented apartments elegantly fitted out with sea shells.

Coastal erosion means that today there’s very little left other than a few alcoves, a corroded railing and some rough steps.

But it’s the long since collapsed original cave, also known as St Rule’s Cave, that has a much deeper connection to the history of St Andrews and indeed to the very foundation of Scotland.

It’s here, according to one legend, that St Regulus (aka Rule) is said to have stayed when he was shipwrecked in the 4th century whilst carrying the relics of Saint Andrew, who became Scotland’s patron saint.

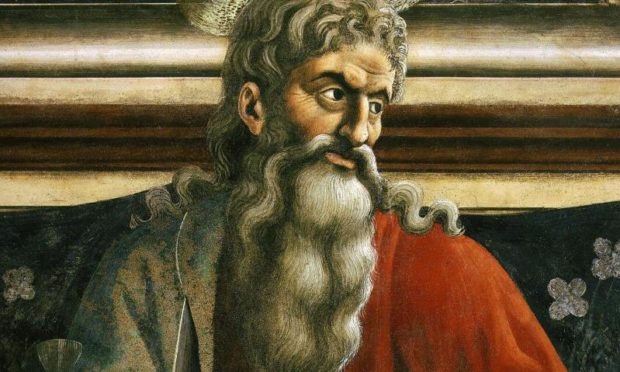

The story goes that in 357AD, some 297 years after Galilean fisherman Andrew – one of Jesus Christ’s 12 disciples – was crucified by the Romans in Patras, Greece, an angel told the Greek monk St Regulus in a dream that he should take the hidden relics of Andrew “to the ends of the earth” for protection, and wherever he ended up, he should build a shrine.

Carrying the saint’s right hand, the upper bone of an arm, a kneecap, and one of his teeth, and accompanied by 17 monks and three nuns, St Regulus was shipwrecked in St Andrews Bay where he was washed up on the shores of the then Pictish settlement that would become St Andrews, taking shelter in what would become known as St Rule’s Cave.

Historians have long surmised whether St Regulus really was taken in and supported by the local King of the Picts or whether the relics were in actual fact brought to Britain in 597AD as part of the Augustine Mission and then to Fife in 732AD by Bishop Acca of Hexham, a well-known collector of religious relics.

What can’t be disputed, however, is that a monastery was built in St Andrews to apparently house relics, and in 1070 King Robert I ordered the construction of St Regulus Church with the larger St Andrews Cathedral built thereafter.

St Regulus Church’s 33 metre tall St Rule’s Tower, built by Culdee monks, still stands today more than four centuries after all traces of Scotland’s relics of Saint Andrew were destroyed during the Reformation.

This brought to an end the role of St Andrews Cathedral as the centre of Christianity in Scotland and a pilgrimage site during the Middle Ages.

However, the name of Saint Andrew lives on through the name of the Fife town, through his status as the patron saint of Scotland and through the saltire which represents his martyr’s death by crucifixion on a distinctive x-shaped cross.

It’s not just Scotland, though, which celebrates Saint Andrew: Russia, Romania, Barbados, Georgia, Ukraine and Greece are amongst places worldwide that also show patronage.

One man with a unique insight into how St Andrews Day is celebrated in Romania is former St Andrews man Peter Herron, 46.

The cartoonist, illustrator, graphic designer and writer has lived in the Pantelimon district of Bucharest with his Romanian-born partner Anca Banaseanu, 39, for six years.

Growing up in St Andrews, the former Langlands Primary and Madras College pupil spent many an afternoon climbing the rocks at the Castle Sands exploring its many nooks and crannies.

But whereas Scotland’s association is tied to the relics being brought to St Andrews, Romania has a much more direct – and indirect – connection.

“Saint Andrew is credited with bringing Christianity to Romania, but like with most Christianised countries, the integration of the new religion would meld with the then Dacian – and pagan – religious beliefs to make the transition smoother,” says Peter.

“After the adoption of Christianity, Saints Peter and Andrew became the patron saints of wolves, therefore, tying that symbol already etched into the Romanian mind to the new deities.”

Peter says that even in 21st century Romania, many Romanians still hold on to the old pagan, now Christianised, rituals.

Despite Nicolae Ceaușescu’s policy of forcing Romania’s rural communities into concrete city blocks, wheat, barley, millet and of course garlic, still hold major significance on Saint Andrews day.

A single grain of wheat is placed into the earth and the length of the root that is grown from it correlates to how prosperous the following year will be.

“Although, most lack cattle now, the ritual of making drinks from millet or wheat still holds a significance as it was thought if you make the drink and share it with your neighbours, the milk produced by all would be healthy,” he says.

“However, as most readers of Bram Stokers ‘Dracula’ would expect, garlic holds a singular power.

“On the night of the celebration of Saint Andrew, Romanians traditionally believe that it is one of the occasions where the spirits of the dead could roam freely, either to haunt or harm, or both.

“They would take the bulbs and rub them against any entry point to a home, whether it be gate, window or door. The ordeal of the roaming spirits would only be broken when the first rooster crows!”

Saint Andrew is also the patron saint of Russia, and even in the Grand Kremlin Palace in Moscow, there’s a St Andrews Room – the former throne room of the Tsars – where, high on the ceiling, there are ornate images of St Andrew on his cross.

Dr Dmitry Fedosov from the Moscow-based Institute of World History at the Russian Academy of Sciences told The Courier November 30 is not widely celebrated in Russia with the possible exception of some Orthodox believers.

However, it certainly is celebrated by the Moscow Caledonian Club of which he is a member.

The club’s flag is half Scottish Saltire and half Russian naval flag, which incorporates the saltire.

“The Russian naval flag was introduced by Peter the Great, discarded by the Communist regime, and recently restored by the Russian government,” says Dmitry, who is a regular visitor to Dundee and an avid Dundee United fan.

“It features the blue saltire on white, a precise mirror image of the Scottish national banner. It is not the case of a chance resemblance.

“St Andrew, of course, is our common patron, and the opening passage in the venerable Declaration of Arbroath affirms that the Scots originally came from Greater Scythia, i.e. the steppes of southern Russia (or present-day Ukraine) where that Apostle allegedly preached.”

Dmitry has recently edited for publication Russia’s oldest existing statutes of the Scottish Order of St Andrew, dated 1720, but probably going back to its foundation in 1698 by Tsar Peter the Great.

Dmitry says the question is not whether there was a Scottish influence, but rather who was the instrument of that influence when the cross of St Andrew became a national device in Petrine Russia.

“Among the circle of important Scots surrounding Peter the Great,” he says, “I would suggest General James Daniel Bruce whose kinsmen at Clackmannan were ardent Jacobites, and who was expert in armorial matters, let alone the fact that he himself wore the Star of St Andrew, and the saltire is the main charge of the Bruce shield.

“The strongly influential Scottish party at the court of Tsar Peter also included his chief advisor General Patrick Gordon of Auchleuchries (1635-1699).

“There was also Major General Paul Menzies, Admiral Thomas Gordon, Professor Henry Farquharson who taught maths and navigation in Moscow and St Petersburg, the head of Russian medicine and Tsar’s personal physician Dr Robert Erskine, and many others.”

Newport-based author and broadcaster Billy Kay addressed the Moscow Caledonian Club when he was in Moscow to collect material for a programme in 2015.

It was then that he discovered the amazing story of soldiers on the Georgia/Russian border singing Flower of Scotland with an historian and one of the border guards quoting the Declaration of Arbroath in Russian.

Billy is also fascinated, however, by links between the St Andrews Cross and the Americas.

In the American South, the saltire was linked with the red battle flag of the Confederacy which is now, unfortunately, often associated with right wing groups.

“It was probably because of Sir Walter Scott rather than Scots and Scottish heritage that they chose that flag,” says Billy.

Billy once interviewed Perthshire’s John McGhie whose father, the Rev William McGhie, came to design the flag of a proud and independent Jamaica and based it on his beloved Scottish saltire.

With at least 25 million North Americans thought to be of Scottish decent, St Andrews Societies are also extremely popular.

Last November, Billy was presented with the prestigious Mark Twain Award at the 263rd anniversary banquet of The Saint Andrew’s Society of the State of New York in recognition of his efforts to “help the Scottish community envision the future, identify paths to success, and carry out a vision”.

As an avid football fan, however, Billy particularly likes the story of another Scot Alexander Watson Hutton, dubbed ‘the father of Argentine football’, who introduced football at the St Andrews Scotch School in Buenos Aires in 1882.

Two years later the Glaswegian, who had Fifer parents, established the Buenos Aires English High School and a former pupil’s team was founded in 1898; which became known as the Alumni Athletic Club.

After serving as a successful administrator and referee, Hutton re-established the Argentine Association Football League – the earliest known league out-with the UK- and became its president.

In those early years, two teams called St Andrews and old Caledonians – both with saltires on their shirts – famously vied for the title on 13 points apiece. A play-off was ordered and St Andrews won the match 3-1.

Former North East Fife MP Stephen Gethins, now Professor of Practice in International Relations at St Andrews University, has a keen interest in how Saint Andrew helps connect Scotland to its friends and partners across the world.

Having seen at first hand the links in the Ukraine and Russia, he remembers taking the ferry from Brindisi in Italy to Patras in Greece, on a student inter-railing holiday.

He stepped off the boat and into the town where Andrew was executed.

Inside the beautiful churches that carry Andrew’s name in the town can be seen some of his other surviving relics where he served as bishop and was martyred by the Romans.

Stephen has also visited the Sint-Andrieskerk, St Andrews Church, tucked away in Antwerp.

“If you look very carefully you will find a small portrait of Mary Queen of Scots,” he says. “Two of her ladies in waiting fled to Antwerp after her execution, where they prayed at the church and are also commemorated there.

“Even in the Holy Land itself you will find Scots using the connection to St Andrews.

“On the shores of the sea of Galilee sits St Andrews Church, Church of Scotland in the ancient city of Tiberius that welcomes Scots and those from throughout the world overlooking the spot where Andrew was a fisherman.

“In Jerusalem overlooking the city walls you can take a moment for quiet reflection at the St Andrews Scots Memorial Church Jerusalem.

“The church was built to commemorate Scottish soldiers who fell during the war and is said to evoke images of a Highland castle, though when I was there it was a welcome place of quiet reflection away from the busy traffic and heat of Jerusalem in the high summer.”