Michael Alexander speaks to world renowned astrophysicist and recently appointed first female Astronomer Royal for Scotland Professor Catherine Heymans about her research into dark matter, space time – and aliens!

A long time ago in a galaxy far far away, a ray of light set off on its journey through the universe.

For seven billion years, this ray of light travelled through the vast expansive voids of space and time.

But its path got twisted and turned by the gravitational pull of all the invisible structures around it.

Then in the last nanosecond of this ray of light’s life, it was caught by a telescope here on Earth.

It bounced from mirror to mirror to be consumed in a camera, and moments later appeared on a computer screen.

Inspirational

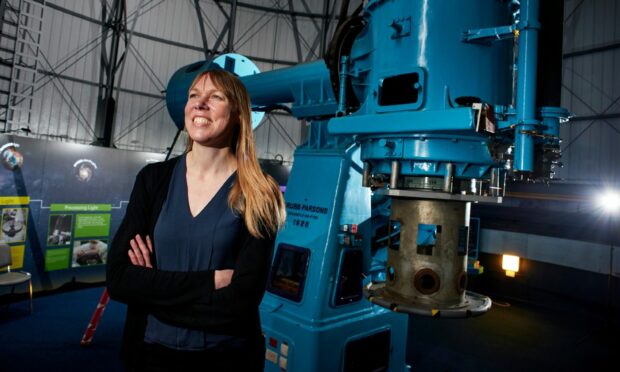

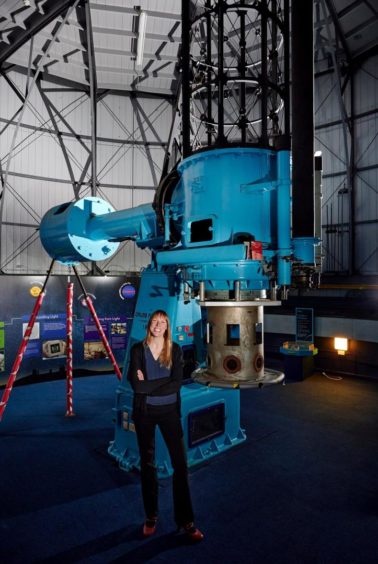

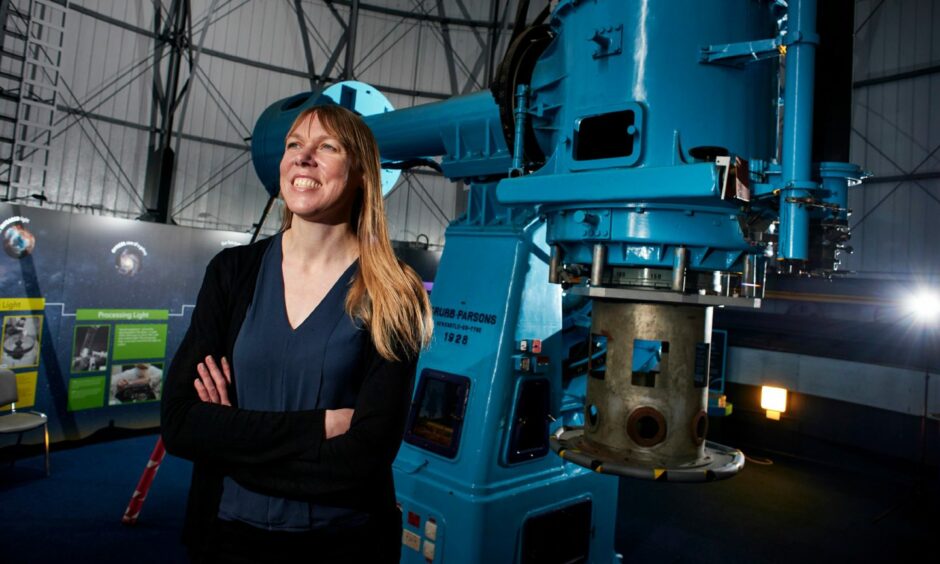

It’s easy to be inspired by the words of Professor Catherine Heymans from Edinburgh University as she enthusiastically describes how, for more than 20 years, she’s been catching light in remote mountain top observatories all around the world.

She’s recorded billion year old messages from over 100 million galaxies.

She still gets a massive kick when an image appears on her screen and she knows she is literally the first person in the history of the universe to see these galaxies because no one has looked at these patches of sky before to this depth.

Yet as she describes the “gorgeous glowing glittering whirlpools of stars” that act as beacons of light in our cosmos, she laughs that she actually hates galaxies!

The reason why she’s spent so much of her time collecting all of this light over the years is because she wants to interrogate it to find out about all of the invisible darkness the light has passed on its journey to planet Earth.

The dark side…

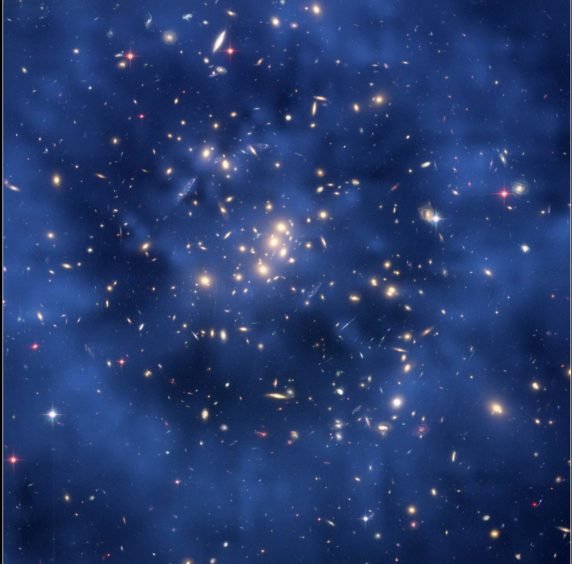

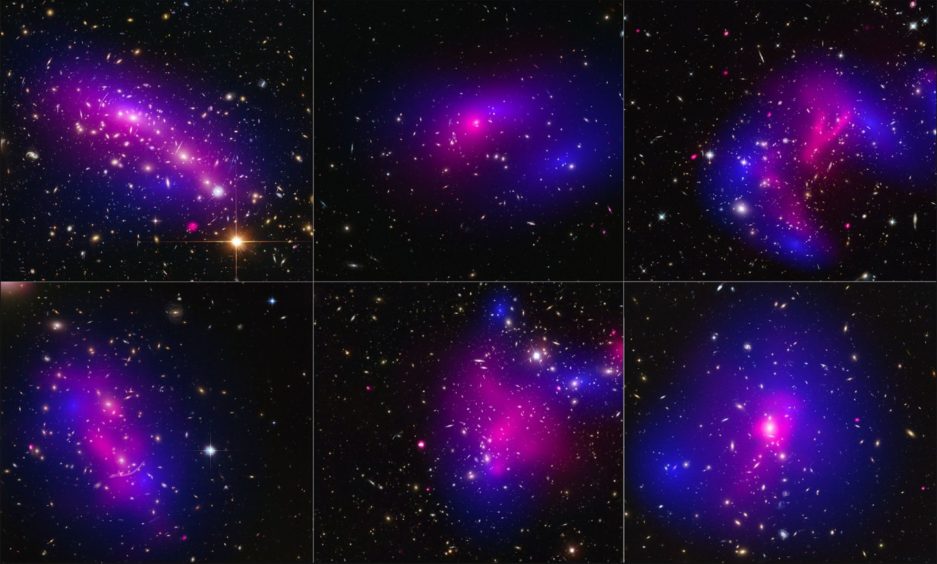

“The area I work on is trying to understand the dark side of our universe,” says the world-leading expert on the physics of the so-called dark universe.

“What we can see only accounts for less than 5% of the universe.

“The other 95% is dark and invisible, and the only reason why we know it is there is because of the effect it has on the things we can see.

“But when you can’t explain 95% of the universe- because our entire knowledge of particle physics only explains 5% of our universe – it’s a kind of a bit of a failing for science!”

Catherine says the great thing about science, “unlike religion”, is that “you don’t have to believe everything you are told”.

In fact, scientists are encouraged not to believe everything they are told.

Instead, they are encouraged to question everything – even if that involves the “heresy” of challenging Albert Einstein!

“Einstein totally revolutionised our understanding of gravity when he came up with his theory of relativity,” she says.

“But this is one thing we’re actually questioning today – maybe his theory isn’t complete. Maybe we need to go beyond that to explain what we’re seeing in the universe.

“Or maybe there’s something completely different going on and we have to completely turn physics on its head.”

In search of answers

Catherine is hopeful that by the time she retires – which is some way off yet – the “biggest questions” about dark matter will have been answered.

Since 2014, a site in Chile has been alive with construction workers, engineers and scientists building the new Vera C Rubin Observatory.

Celebrating Vera C Rubin, the astrophysicist who found the first crystal clear evidence for the existence of dark matter, the observatory is scheduled to create the first movie of our universe.

It will photograph the entire southern night sky every three nights on repeat for 10 years, looking for anything that moves. Rubin will be able to locate any potential killer asteroids that could one day obliterate planet Earth.

However, more immediate and closer to home, having recently been appointed the first ever female Astronomer Royal for Scotland, Catherine also hopes to open up astronomy and science to a whole new generation – whatever their backgrounds.

Catherine, who is professor of astrophysics at Edinburgh University and Director of the German Centre for Cosmological Lensing at Ruhr-University Bochum, was recommended to the Queen for the role by an international panel, convened by the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

What is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland?

Created in 1834, the position of Astronomer Royal for Scotland was originally held by the director of the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh.

Since 1995, however, it has been awarded as an honorary title.

The previous holder, Professor John C Brown, passed away in 2019.

As the 11th Astronomer Royal for Scotland, Catherine’s main focus will be on sharing her passion for astronomy with Scots from all walks of life.

One of her first targets is to install telescopes at all of Scotland’s remote outdoor learning centres, which are visited by most of the country’s school pupils.

“I want to use the title to help motivate people in Scotland to reconnect with the night skies,” says the mother-of-three school age children.

“More importantly I want to use it to connect with young kids and kids from all backgrounds – not just the kids that come to the science events that are put on.

“It’s so great when kids look through telescopes, see the rings of Saturn and they go ‘wow it’s just like it is in the book’.

“But so many kids just don’t get the chance to do this.

“They spend so much time on screens nowadays. I want to get kids off screens to really embrace reality and hopefully develop a life-long passion for astronomy or, even better, science as a whole.”

Great honour

Catherine says it’s a great honour to be appointed the first female Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

When she was first asked to be considered, she laughed it off.

She he felt she was “too young” and believed there were “some incredibly eminent and very well established” astronomers in Scotland who would fit the bill ahead of her.

When her appointment was announced, however, she got “a lot of heart felt emails” from other female astronomers saying how important it was for them.

Shaking off her “imposter syndrome”, she was also supported by astrophysicist Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell who, despite discovering radio pulsars while doing her PhD in 1967, was not one of those recognised by the 1974 Nobel Prize for Physics. The award went to Burnell’s PhD supervisor instead.

“I was thinking – if you don’t see people in the high senior roles that don’t look like you, you feel it’s unachievable,” says Catherine.

“I think it’s really important for young girls – and also boys – to see that anyone can do this job, if they work hard enough, whatever their background.

“It is really important we have a woman, but it’s not the reason I got the job. It wasn’t a female only search!”

Lifelong love of science

Catherine loved science and physics from a young age.

She had an “amazing” physics teacher who got her into space science.

At school in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, she fondly recalls a visit from Helen Sharman, who, in May 1991, became the first British astronaut in space and the first woman to visit the Mir space station.

However, she can’t say whether being a girl made it more difficult to get into science because, in her home town, there was a “bit of an anomaly” where one state school was a girls-only school and the other a boys-only school.

She admits, though, it was “quite a shock to the system” when she arrived at Edinburgh University to study astrophysics and discovered that out of 90 students, only seven were female.

During her entire four years as an undergraduate, she wasn’t ever taught by a female academic.

“Thankfully that’s not the case now – things have really changed,” she says, adding that she didn’t get into astronomy until working as a student tour guide at the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh.

“But it was a bit of a shock!”

Dark skies

Away from the urban glow of the Central Belt, Scotland is blessed with some of the darkest skies in Europe.

Catherine is delighted that a lot of people turned to the skies during lockdown as a means of “escaping”. The Astronomical Society of Edinburgh, for example, saw a 30% increase in membership over lockdown.

People don’t need any equipment to enjoy the brightest objects in the night sky.

She recommends a good pair of binoculars over what could turn out to be an expensive, less useful, telescope.

But even in summer, there’s plenty to see and as we continue chatting, conversation again turns to Einstein’s theory of relativity and the very concept of time itself.

Spice Girls v Hanging Gardens?

“Right now in the summer skies there’s a constellation called the Summer Triangle,” she says.

“It’s basically the three brightest stars you can see in the summer sky.

“What I love about these stars is they look about the same brightness.

“One of them is 25 light years away – so the light has taken 25 years to get to us. You can think about what you were doing 25 years ago, which is interestingly when the Spice Girls released their first single!

“But interestingly another one in the triangle is one called Deneb. The light from Deneb left 2616 years ago which is like going back to King Nebuchadnezzar and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

“But they both look about the same brightness in the sky. If you look from one to the other it’s ‘Spice Girls – Hanging Gardens of Babylon’”, she laughs.

“I just love this. The sky looks like it’s two dimensional but it’s not – it’s three dimensional. You don’t need a telescope to really appreciate that and think about what was happening when that light left those stars.”

So what then is ‘now’?

When looking at stars billions of light years away, it’s quite a thought that the really distant galaxies probably don’t exist anymore.

Which begs the question– ‘so what then is ‘now’? Is ‘now’ when the light left those stars potentially billions of years ago, or is ‘now’ the moment we are seeing them?

“You’ve put your nail on Einstein’s theory of relativity!” laughs Catherine enthusiastically.

“That it is all relative to each other. So ‘now’ is a concept for us in our point of space and time, but for someone else somewhere different in the universe they have a different concept of time.”

It’s fascinating stuff which inevitably, leads on to a conversation about aliens.

Are we alone in the universe?

Catherine is convinced we are far from alone in the universe. However, there is a catch.

“If our theories about the universe are right, then our universe is infinite,” she adds.

“In an infinite universe you’ve got an infinite number of galaxies, and in each galaxy you’ve got like 100 billion stars – easily.

“All of the observations of stars recently are picking up planets going round them.

“I do not believe we are the only living civilisation in our entire universe. There’s definitely life somewhere else in the universe.

“However, whether that life is in the same space and time zone as us, is unlikely.

“If you think about how old our planet is and how old our sun is and how short civilisation has existed on our Earth, our civilisation is just a tiny nanosecond in the lifecycle of our Earth.

“So the concept that there will be another civilisation in that same short timeframe in the right space and time for us to communicate with them is highly unlikely.

“So yes, I think there are aliens somewhere else in the universe but no I do not think we’ll be able to communicate with them, sadly. Although we’ll try!”