How do we protect Scotland’s historic landmarks from climate change? Michael Alexander speaks to Historic Environment Scotland about the action being taken and the critical challenges that lie ahead.

From intimidating castles perched on precarious coastal pinnacles to secluded monasteries hidden away on remote wave-pounded islands, the strategic locations of Scotland’s historic buildings were usually no accident.

But while our ancestors often chose such locations with defence, industry or spiritual pondering in mind, many historic sites are today threatened by a far more insidious, more powerful force – climate change.

Research carried out by Historic Environment Scotland (HES) a few years ago concluded that 90% of the 336 historic properties it manages are at potential risk from rising sea levels, torrential rain, violent thunderstorms, floods and landslides.

When works already being carried out was taken into consideration, around 50% of properties were found to be at “high or very high level of risk”.

Today, HES is working on a revision to that risk assessment that brings in more up to date data.

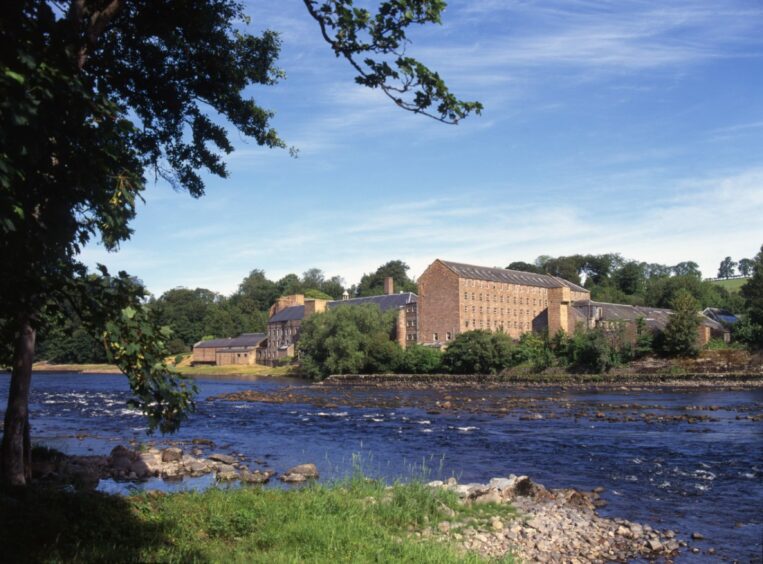

Properties under threat range from the Neolithic settlement at Skara Brae in Orkney to Inchcolm Abbey in the Firth of Forth, and from Stanley Mills on the River Tay to the Black Watch’s home at Fort George on the Moray Firth.

While work is being carried out to defend and maintain properties and ensure that 41,000 heritage objects are preserved, however, a warning has been sounded that not all of the 336 HES properties may be saved long term.

Understanding the impact

One man charged with trying to understand the impacts of climate change on historic properties and the different risks associated with it is HES climate change scientist David Harkin.

A Glasgow and Portsmouth university graduate with a background in geology and Earth science, David did his dissertation on the impact of a changing climate on masonry used in historic structures.

He says the strategic location of many historic properties is “absolutely one of the driving factors” for climate risk.

On a more positive note, however, there is also much that can, and is, being done to adapt to change.

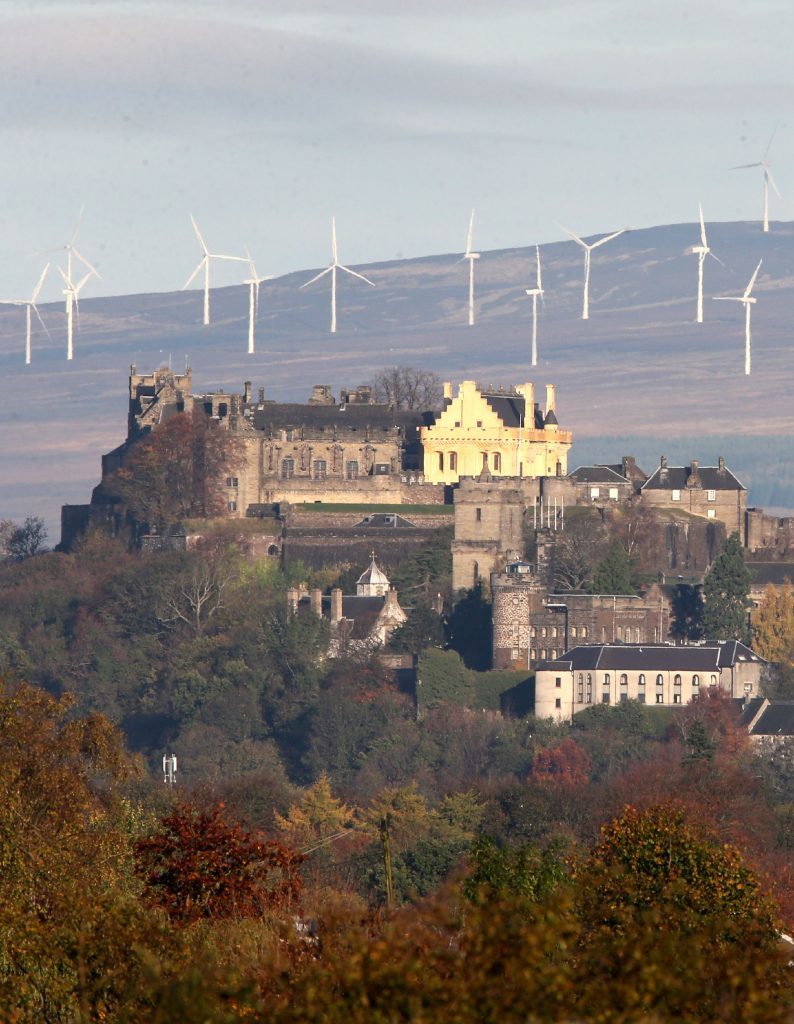

“It’s no accident that Edinburgh Castle is on top of a volcanic crag,” he says.

“It’s no accident a lot of our coastal sites or settlements were built in strategic points because it offered the people some sort of natural benefit.

“But naturally today, that means these properties are at a heightened state of risk from flooding, sea level rise, increasing rates of coastal erosion etc.

“There are lots of different scales of risk or impact. There are what I would call the macro scale impacts. That’s coastal erosion, flooding, the sort of large, natural hazard events.

“But there’s minute micro scale impacts as well around how a piece of stone decays and weathers in the environment that it’s in and how climate change can exacerbate and speed up rates of decay.

“There’s a whole different scale of risks and impacts that our properties are exposed and vulnerable to.”

For many sites, extremes of climate is nothing new. Many traditional buildings, built from locally sourced sand stone and slate, were built with the wet Scottish climate in mind.

However, changes in global climate is increasingly being felt. Sea levels, for example, are rising in Scotland by more than 3mm a year.

Climate scientists are also predicting that Scotland will experience warmer, wetter, winters while summers will be hotter and drier with greater extremes.

Impact at Skara Brae

One high profile place where coastal erosion is very active and visible is at the Neolithic settlement at Skara Brae on Orkney.

Yet David says it has to be remembered that climate change is also part of the site’s 5000-year-old story.

“We know the Skara Brae site exists because it got uncovered in a violent series of winter storms back in the late 1800s,” he says.

“When the site was occupied, it would have been 1km inland.

“It wasn’t a coastal property. Coastal erosion is part of that site’s story.

“But there are have been coastal defences in place since the 1920s/30s to protect the site, and if you look at aerial photography you can see that without the coastal defence, part of the site would already have been lost.

“So the future for somewhere like Skara Brae. I wouldn’t say there’s an imminent tomorrow threat that it could be lost as a result of climate change.

“But we don’t know how severe climate change is going to be in the future, and that future is not yet set in stone.”

David explained that HES has had an active climate change team for over 10 years.

During that time, there have been many activities, projects and research to try and better understand and manage the climate change problem.

There are some sites where there have already been active interventions.

Fort George

At 18th century Fort George, for example, there’s a particular issue with coastal erosion.

A vulnerable part of the site that was quite imminently under threat has seen HES working with the Ministry of Defence to put in place a rock barrier.

Crucially, however, HES also now has a digital documentation team operating on a multi-year project to create 3D models of all their sites.

“They go out and they scan the properties,” he says.

“They create this digital model and that gives us almost millimetre precision model of the sites.

“At a place like Skara Brae they’ve been going up and doing that every two years, for the past eight years, and that means we’re able to monitor and track how much of the coast is disappearing.

“But it also has to be remembered that when part of the coast disappears, it goes somewhere else. “So we are tracking not only erosion but accretion in the bay that Skara Brae’s in.”

Inchcolm Abbey and Stanley Mills

The 12th century-founded Inchcolm Abbey in the Firth of Forth is another vulnerable site where David says the risk and impact of climate change is “quite apparent”.

As a low-lying island in the middle of the Forth, there’s an active coastal erosion threat with an additional threat from sea level rise.

At Stanley Mills on the River Tay between Perth and Dunkeld, river flooding is the greatest risk.

“Actually that’s not a surprise,” says David. “The mill is where it is because it needed to borrow the power of the water to operate. A flood risk at a mill is not breaking news as such!”

What’s becoming increasingly unpredictable, though, is how changing rainfall patterns can increase the likelihood of extreme flood events.

“I can’t say we’ve experienced a particularly extreme flood event at Stanley Mills yet,” he says, “but that doesn’t mean it won’t happen in the future.”

With many sites in ruins, David loves the fact that many HES properties tell a long-term story.

They may have been reduced to ruin by a passing army 500 years ago, or track a change in ownership. They all give a unique insight into the past.

Arguably, and almost certainly, climate change is the “most current and real threat and risk to them” which, in its own way, will influence their future.

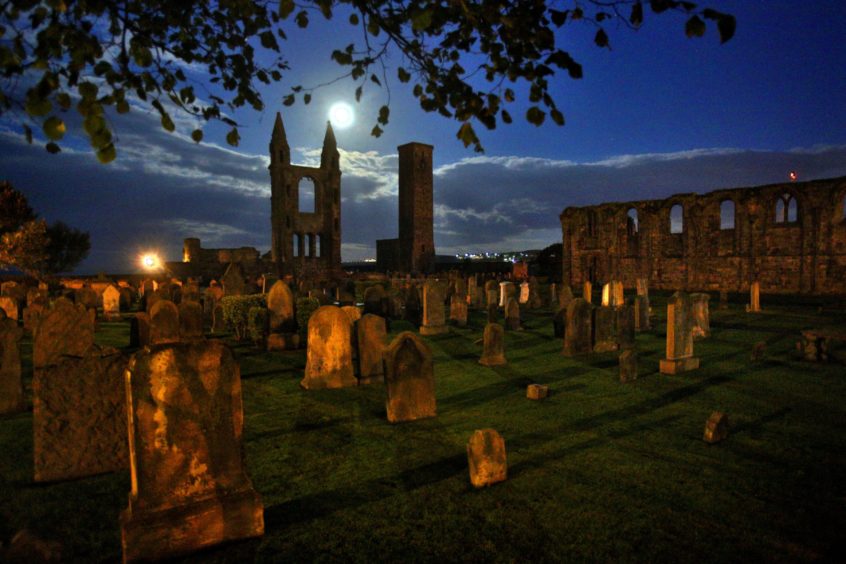

David says climate change is a “factor” for the recent decision to close the ruined sites at St Andrews Cathedral and Arbroath Abbey.

With “different elements at play”, he says the closures there are “precautionary” to “get a bit of a head start on a good high level survey of some of these monuments”.

Ancestors’ wisdom

David says a “twist in the tale” is that the materials used by our ancestors in the construction of many monuments HES look after are actually pretty well suited to Scotland’s wet climate.

Choose the right bit of sand stone, for example, and take good care of it, and it’ll last for centuries.

At the same time, because many HES managed properties are in ruins, they are not always the best examples of how robust ancient buildings can be.

In future, however, HES will have to increasingly think about how climate change effects different decay patterns.

So where’s the line between trying to save a property and accepting that it can’t be saved?

“I think any kind of organisation like Historic Environment Scotland in the 21st century has to be quite pragmatic and realistic about the challenge of climate change,” he says.

“The future is not set in stone yet so we don’t know how severe the changes will be.

“But in a world where there is quite catastrophic change in the climate, the reality is that some places we look after won’t exist in the future. That’s the hard reality of it. But that doesn’t have to be the future if that makes sense – it’s still up for grabs.”

David says there’s a constant stream of new improved data coming out about climate change predictions and part of his job is to keep on top of that.

The approach they’ve taken in the past with climate change projections is to look at the worst case scenario – or “prepare for the worst and hope for the best” as one of David’s colleagues puts it.

In general, he concedes that the physical changes associated with climate change are “probably not good news for a lot of the places we look after”.

If a decision is taken to allow a site to decay naturally, however, there’s opportunities, he says, for people to engage in the heritage in a way that they might not otherwise have been able to.

“If there’s a site identified as being at quite high risk of being lost,” he says, “you can undertake emergency excavation at that site and engage with a community to take part in those digs and learn stuff about a site and let the site give up its secrets that it might otherwise have kept hidden away.”

Hope and optimism

David says it can be difficult doing his job some days as there is a “constant stream of doom and gloomy messaging” around climate change.

He does, however, remain hopeful and optimistic for the future.

With HES’ own climate targets aligned to the Scottish Government’s – aiming to be a net zero organisation by 2045 – emissions at Edinburgh Castle, for example, are down about 50% since 2008/2009.

Sustainable policies will also be promoted at COP26 in November while promoting the values of cultural heritage.

David also thinks Scotland’s historic environment is a “survivor” by its very nature.

“It is our link to the past but it has a really significant role to play in where we go next as a country,” he says.

“If we can demonstrate good practice like at Edinburgh Castle where we are reducing carbon emissions or if we can use the risk and impacts of climate change at a place people really care about, that might promote or prompt action in people because you have that sort of emotional attachment to these places.

“It has a really live and active role in encouraging good practice and where we go next.

“Sites might not look exactly the same as they do now in 100 or 150 years. Even without climate change they probably wouldn’t look exactly the same as they do now.

“But I do think elements will be around and it will essentially tell us whether we were successful or unsuccessful at getting a handle on the climate crisis. That’s quite a scary thought actually!”