Michael Alexander speaks to tenacious veteran Dennis Hayden and hears why he is still fighting for ‘honesty’ about the health implications of Britain’s nuclear weapons test experiments from 1952 to 1967.

After driving for miles through the searing heat of the desert on dusty tracks, the Land Rover stopped within sight of abandoned tanks and aircraft on the horizon.

Sweating in the 37 degree centigrade heat, the men dressed in khaki shorts and shirts were invited to jump out, stretch their legs and take a look around.

Amongst them was 21-year-old RAF junior technician Dennis Hayden who had just arrived for his year-long stint at the site of the British nuclear tests, Maralinga in South Australia.

Thinking back to that day in early 1966, Dennis, now 77, recalls how the new arrivals were shown craters from atomic test blasts.

They were even invited to climb into a 30-foot deep bomb crater after the ranger leading the expedition declared it “perfectly safe”.

However, with little idea of the health risks and with no protective gear available, Dennis recalls how he declined the invitation because he thought it was “barmy”.

“When I got to Maralinga the whole place was fizzing with radiation basically,” he explains in an interview from his home in Gloucester.

“But we had no idea of the harmful effects from the radioactive particles at the time.

“Everyone who arrived there went through an indoctrination process. We went to the nuclear test area. We were invited to go to the edge of the bomb crater.

“This range commander or his assistant said ‘it’s perfectly safe lads you can walk down into the crater’. Some did. I thought it was barmy.”

Cold War paranoia

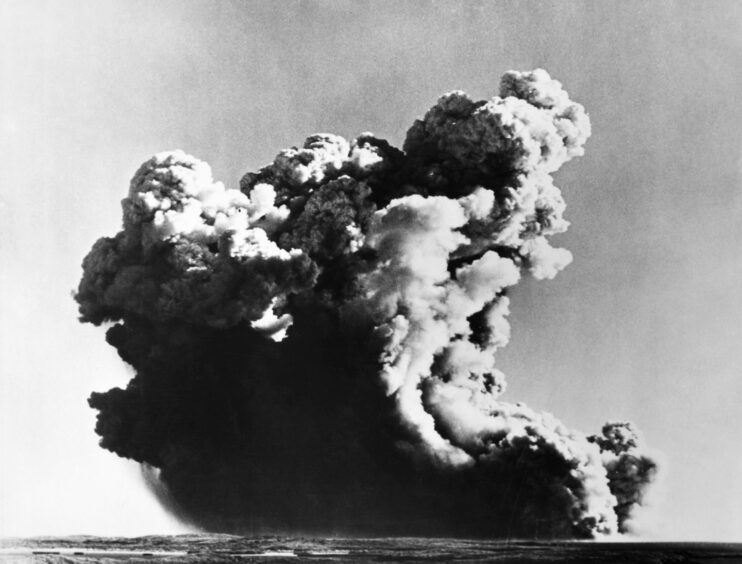

At a time of Cold War paranoia between East and West, when the world’s nuclear arsenal was escalating dramatically and testing of ever bigger more powerful bombs was rife, Mr Hayden explains no nuclear tests were carried out at Maralinga during his stay.

However, in the run up to 1963, about 600 tests had been carried out in the area which released small quantities of plutonium into the atmosphere.

Scientists were often seen in the craters wearing protective gear and later, when the site was being decommissioned, plutonium was found buried in pits in an area known by servicemen as “The Cemetery”.

However, the military were not given respirators during his stay, he says. They would camp out next to the test sites and it was not uncommon for dust storms to leave everything covered in a thin layer of dust.

In 1967, just a month before Mr Hayden’s 12 month tour was due to end, his eyes became acutely inflamed and he was sent to a Royal Australian Air Force hospital 500 miles away, outside Adelaide.

There, he was diagnosed with acute iritis – possibly caused by radiation exposure.

“When I got to this sick bay a nurse said ‘you are from Maralinga – we’ve had loads of people down with all sorts of health problems’,” he recalls.

On arrival back in England, he ended up as a patient at the military hospital, RAF Halton.

By mid-1969 he was taken off air movement squadron load team flying duties, which had involved international travel, and graded medically unfit for any further RAF service except ‘light’ desk work restricted to the UK only.

Between 1969 and 1974, he spent about 100 days in various military hospitals.

He was informed by military doctors he had no chance of further promotions. His RAF career was finished.

Coming out of the RAF aged 30 after 12 years’ service, and a two year apprenticeship, Mr Hayden worked on stock control with the British Aircraft Corporation in Saudi Arabia for three years.

The good conditions and pay compensated him, he said, for his poor financial state leaving the RAF and, having got married, was able to buy his first house.

Health issues

However, he had ongoing health issues and when he eventually managed to secure a 20% disability war pension allocated from the then DHSS, he had come to realise there were many other ex-nuclear veterans out there struggling to be recognised.

“When Scottish veteran Ken McGinley set up the British Nuclear Test Veterans Association (BNTVA), I was working as a sales consultant,” he recalls.

“By 1985 – the year the Australian Royal Commission was coming over here to hold the British government to account for the mess left in Australia – that’s when I joined the BNTVA. I didn’t take too much of an active interest at that time. I was too busy trying to make my way in life.

“But it wasn’t until about 1992, when I fought for my pension, that I actively started to campaign and do anything.”

Campaigning for the government to award war pensions to nuclear veterans, their widows and descendants, in the late 1990s he founded the Combined Veterans’ Forum which in 2003 became the Combined Veterans’ Forum International.

That’s when he began exchanging information with UK, Australian, and New Zealand veterans who had attended UK nuclear weapon tests in Australia and the Pacific between 1952 and 1967.

This was to assist the Atomic Veterans Group Litigation led by Rosenblatt Solicitors of London that took place between 2005 and 2013.

In 2009, campaigners won a trial which allowed 1000 cases to go to full high court based on evidence that radiation fallout caused death and that New Zealand veterans had 300% more genetic damage than veterans who’d never attended a nuclear location.

However, the Ministry of Defence appealed against it and when it went to the supreme court, the campaigners’ verdict was overturned by four votes to three.

The campaigners maintain the position that this was an unsafe verdict.

MoD response

The Ministry of Defence has repeatedly responded by saying it is grateful to all the servicemen who participated in the British nuclear testing programme. They contributed to important tests that helped to keep Britain secure during the Cold War.

However, Mr Hayden believes efforts are being made by the MoD and government to “airbrush veterans from history” and “wait for them to die” so that no further compensation is required.

He describes the whole thing as a “big experiment” whereby the nuclear weapons effects on equipment and the effects of radiation on men turned them into “human guinea pigs”.

He is full of praise for “tenacious campaigners” like Dave Whyte of Kirkcaldy, who has featured many times in The Courier.

New book on British nuclear tests

Mr Hayden has now recorded the entire episode in his new book, The UK’s Nuclear Scandal, written from sourced archive and other documents gathered and collated by nuclear test veterans.

Covering the 1952-67 nuclear tests period and what has happened since, the book has been written on behalf of the Combined History Archive of Nuclear Veterans and includes a foreword by a legal practitioner on three continents, Ian Anderson who is currently based in New York.

Since January this year, Mr Hayden says four of the leading nuclear test campaigners have died.

However, it’s in the memory of these people and countless others that the book has been written.

“They are few and far between now,” he adds.

“The nuclear veterans in my experience fall into two camps – there’s the people actively campaigning to do something and on the other hand you have the guys who just want to get together to meet up and then look at the world through the bottom of a rose tinted beer glass.

“Basically, as time has gone on, the government method of trying to kill all this off is to keep denying everything until we are all dead and then of course they are not accountable to anyone. They know dead men can’t speak. And of course are very few veterans left.

“If ever there’s a time to write a book like this now is the time.”

Inspired by military

Born in Salisbury, Mr Hayden’s father was an infantry sergeant all through the Second World War and served in the Korean War.

As a child growing up, they travelled all over the world. They spent time in Hong Kong and Germany.

Mr Hayden said the positive experience of being part of a military family in those post-Second World War years inspired him to join the RAF as a military apprentice at age of 16 in 1960. His brother went into the navy.

However, he hopes the book can help document events for the sake of history.

“My hope in writing the book is not to convince the public because they would probably toss it in the bin – although some might take note of it – but to actually get it to people who will take an interest in it,” he adds.

“I discovered all medical records from Maralinga in Australia have just vanished. It’s like they’ve disappeared off the face of the Earth.

“We’re just hoping anyone out in the public will be interested, particularly if they are interested in history.”

- The UK’s Nuclear Scandal, by Dennis Hayden, is available now.