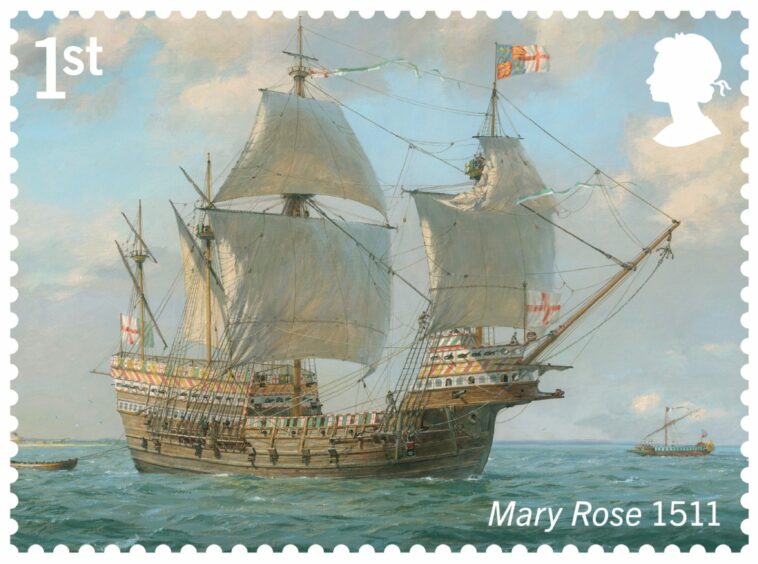

Could the world’s largest 16th century battleship, built in Scotland, have been involved in the sinking of Henry VIII’s favourite ship, the Mary Rose? As St Andrew’s Day approaches, Michael Alexander investigates.

She was the biggest and most heavily armed warship of her time, making the Royal Scottish Navy the envy of the world.

Measuring 240ft by 33ft and armed with 24 Flanders guns and up to 40 smaller ones, the 1000 tonne carrack Michael, known popularly as the Great Michael, was manned by 300 sailors, 120 gunners and up to 1000 soldiers.

Ordered by King James IV in 1505 to support his unrealised ambition of a Scottish crusade against the Ottoman Empire to “reclaim Palestine for Christendom”, the vessel, named after the archangel Michael, was laid down in 1507 under the direction of Captain Sir Andrew Wood of Largo, Fife.

Largest in Europe

As she was too large to be built at any existing Scottish dockyard, a new dock was created at Newhaven, outside Edinburgh, and, upon launch in 1511, she became the largest warship in Europe.

According to the Newhaven Heritage Centre, she had twice the original displacement of her English contemporary Mary Rose, which was launched the same year.

The undertaking was reputed to have used all the best oak that was in Fife (with the exception of the forest around Falkland Palace used for hunting), as well as timber from Norway and France as well as the best wrights from Scotland and France and other craftsmen from Flanders, Holland and Spain.

Chronicler Lindsay of Pitscottie said at the time: “The Scottish King bigged a great ship called the Great Michael which was the greatest ship and of most strength that ever sailed in England or France — to wit she was 12 score feet of length and 36 foot within the sides; she was 10 foot thick in the wall, outted jests of oak in her wall and boards on every side so stark and so thick that no cannon could go through her.”

However, a warship of this size was costly to maintain, and after King James IV was killed at the Battle of Flodden in 1513, she was sold to Auld Alliance partner France for a bargain price and became known as “La Grande Nef d’Ecosse”.

Historians have suggested that due to her impractical size and cost of maintenance, she was allowed to rot at Brest.

However, it was suggested by St Andrews University academic Norman MacDougall in the 1990s that, under her new name, she may have taken part in the Battle of the Solent in 1545 – the French attack on England that led to the sinking of the Mary Rose.

So is it possible that a ship that once made Scotland a naval superpower of Europe helped take on the Auld Enemy England and sink King Henry VIII’s favourite ship?

Who sank the Mary Rose?

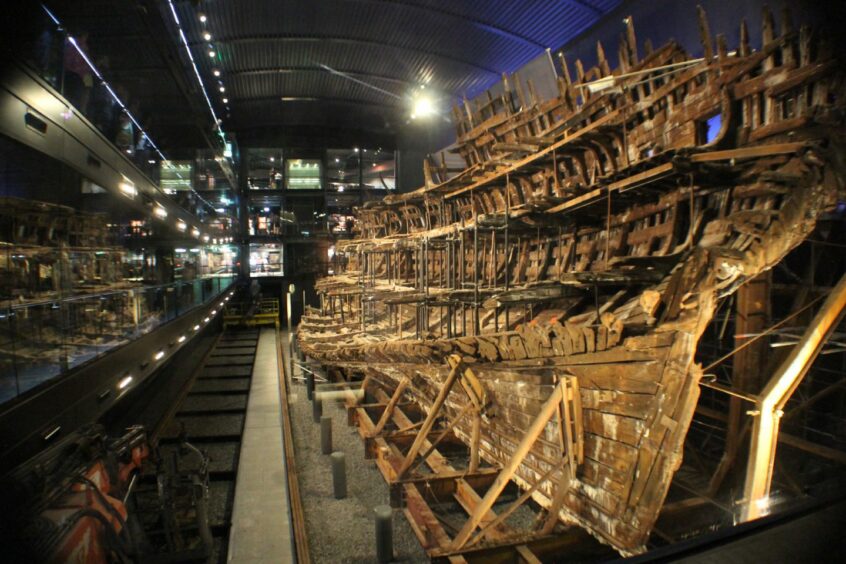

Alexzandra Hildred, Head of Research and Curator of Ordnance and Human Remains at the Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth, says she would love to have time to go through the French archives.

While written French accounts (in particular Du Bellay) state simply and categorically that the French sank the Mary Rose, the only image they have of the Mary Rose in action is an engraving from the 1700s which depicts her already sunk while the Henry Grace a Dieu or Great Harry, built by the English as a response to the Great Michael, engaged with the French galleys.

However, according to accounts, there was no vessel as cumbersome as La Grande Nef d’Ecosse visible within the French fleet.

She was also said to be too large for many of the French harbours and was left to rot.

The most reliable eyewitness accounts state the Mary Rose had fired all of her guns on one side and was turning to fire the guns from the opposite side when she capsized.

“At the time the French suggested they sank the Mary Rose with gunfire,” says Alex, “but this is only one of many suggestions.

Others include foreign crew not understanding orders, too many officers and not enough crew, in subordination, a gust of wind, overmanning, over gunning, captain overstepping his mark, gun ports too low, pump not working, water in the ballast; and just an unlucky stream of events following firing on one side and turning.”

Were Falkland woods protected?

When it came to the construction of the Michael, woodland heritage specialist Dr Coralie Mills, who is an honorary research fellow at St Andrews University, says Falkland’s status as a favourite Stewart royal hunting ground would have largely protected its woodland.

However, Pitscottie’s claim that constructing the Michael stripped all the woods of Fife except Falkland is a “bit of a myth”, she says, for the reason that Fife would already have been very short of a local timber supply by that time.

“We have evidence from dendrochronological dating and dendro-provenaning of historic timbers from buildings in Fife that most timber was being imported into Fife by the mid-15th century, much of it from Scandinavia, and sometimes even earlier than that,” she says.

“James IV was building an entire Scottish fleet at Newhaven, not just the Michael, and I have seen other evidence that Newhaven was drawing on timber from all over the place for building this fleet. I doubt they would have got very far if they were relying on the woods of Fife!”

Dr Mills notes that even Falkland’s old woodland was eventually lost.

When she undertook a historic woodland assessment there with her colleague Peter Quelch some years ago, they found that the old woods were all lost in the 17th and possibly into the early 18thC, and that the oldest woodland cover there now is later 18th or 19th century.

Historian John Gilbert, honorary research fellow at St Andrews University, has also done work on Falkland Park.

While there were still woods in the park in the 16thC, the exchequer rolls record that in 1511-12, wood was taken for naval construction.

“This could have been for the Great Michael which was launched around November 1511,” he says.

“But there is no way of knowing since other ships were being built and repaired at the time.”

Doubt over Great Michael role

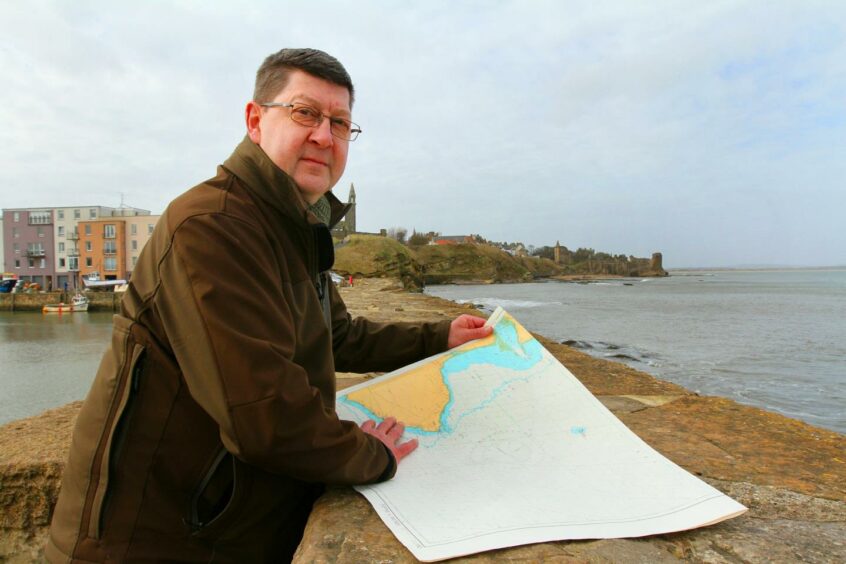

Internationally-renowned marine archaeologist Neil Cunningham Dobson, 65, from St Andrews, takes the view that if the Great Michael, under its new French name, had participated in the Battle of the Solent, “we would have known about it”.

“It’s brave for anyone to turn around and say the Scots sunk the Mary Rose!” he laughs.

In reality, ships like the Mary Rose, “built by people who couldn’t read or write”, often capsized because of stability issues.

What’s not in doubt, however, is that during that period, Scotland was a very significant maritime nation whether that be through shipbuilding or through those that went on to do great things as sea captains and admirals.

The likes of Alexander Selkirk from Lower Largo, who inspired the story of Robinson Crusoe, and Captain Keay, from Anstruther, who commanded the legendary clipper Ariel in the 1860s, are just two Fife names synonymous with maritime adventure in the centuries that followed.

Ahead of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, press gangs would often target Fife villages such was the reputation for seamanship.

And while Captain Andrew Wood of Largo was directly involved in the Great Michael project, which Neil describes as the “Death Star” of its day, the Scottish east coast, including Fife and St Andrews, had their fortunes very much tied up with the sea.

“Sea routes were really what the internet is today,” says the former St Andrews Coastguard member, who can trace his family roots back hundreds of years through the local fisher folk.

“If we just take the east coast, all the burgh ports – some were fishing ports, some were trading ports. You are only 400 miles to Denmark, you’ve got access to the Low Countries.

“They were bringing wood over and we were giving them oats and grain and potatoes. Then herring fishing started. There was a lot of trade going on there. But then of course St Andrews was also a busy place with pilgrims from all over Europe coming to the cathedral.”

Shipwrecks through history

While the earliest mention of a harbour in St Andrews is 1222, Neil’s research into Pictish and Celtic clan chiefs, back to the 4th century, suggests the area around today’s Woodburn Place, next to the Kinness Burn, would have been a natural harbour.

The flourishing of the town in medieval times prompted development of a better harbour.

Rudimentary technology and the perils of the high seas before lighthouses, however, meant that throughout history, including the Viking era, St Andrews and the coast of Scotland, became a graveyard for countless vessels.

Perhaps the most famous shipwreck story of all tied in with the founding of St Andrews itself, and the celebration of Scotland’s patron saint, Saint Andrew, is that of Greek monk St Regulus (aka St Rule).

The story goes that in 357AD, some 297 years after Galilean fisherman Andrew – one of Jesus Christ’s 12 disciples – was crucified by the Romans in Patras, an angel told St Regulus in a dream that he should take the hidden relics of Andrew “to the ends of the earth” for protection, and wherever he ended up, he should build a shrine.

Carrying the saint’s right hand, the upper bone of an arm, a knee cap, and one of his teeth, and accompanied by 17 monks and three nuns, St Regulus was shipwrecked in St Andrews Bay where he was washed up on the shores of the then Pictish settlement that would become St Andrews, taking shelter in what would become known as St Rule’s Cave.

Another version of the story is that the relics were brought to Britain in 597AD as part of the Augustine Mission and then to Fife in 732AD by Bishop Acca of Hexham, a well-known collector of religious relics. St Andrews Cathedral was ultimately constructed to house them.

Wrecks of St Andrews Bay

The United Nations estimates that of three million shipwrecks worldwide, approximately 40,000 of them can be found in UK waters ranging from 10,000 year-old dug-out canoes through to modern day 21st century wrecks.

Not surprisingly, Scotland’s 6000 miles of coastline are peppered with many of these vessels, ranging from ships trashed on rocks long before lighthouses, to warships sunk during the dark days of the First and Second World Wars.

Neil, who helped discover and salvage the world’s deepest and largest precious metal recovery from the shipwrecks of the SS Gairsoppa and SS Mantola in the North Atlantic a few years ago, did his dissertation on shipwrecks between Anstruther and the Eden Estuary from 1800 to the modern day.

A total of 233 separate incidents are recorded during that period, many of which are explored in George Bruce’s 1884 book ‘Wrecks and Reminiscences of St Andrews Bay’.

In reality, however, many shipwrecks through history have never been recorded while others such as ‘General Monck’s treasure’ in the Tay and the wreck of King Charles I’s baggage vessel the Blessing, which sank off Burntisland in 1633, have become the stuff of unsubstantiated legend.

“It would be quite common that ships coming round by Fife Ness – maybe thinking they were heading up the Forth, were heading into St Andrews Bay instead,” says Neil.

“They wouldn’t be able to tack out in a storm and they’d be driven ashore. The same might happen if they were trying to get into the Tay and missed and got into St Andrews Bay.

“When you look at the 16th century charts they show St Andrews Bay as an anchorage, so the boats knew it was safe to come in there.

“But in that period of time, so many ships left port and that’s the last they were ever heard of – you didn’t know where they were going to. If they went down, their wrecks could be anywhere!”