Eighteen months after schools were urged to increase the use of the Scots language as part of a wider drive to improve literacy, a BBC Radio documentary, compiled by Newport-based broadcaster and Scots language expert Billy Kay, is highlighting the efforts to promote the use of Scots in Dundee. Michael Alexander reports.

Oor east coast gibbir iz quite yooneeck,

Itz got thi rehst ih Sco-lind uh’irlay seeck – an’ jehliss,

Thiht that canna speek this Dundee speek.

The words of Dundee street poet Gary Robertson are an unashamed nod to the unique dialect that has developed in the city over the centuries.

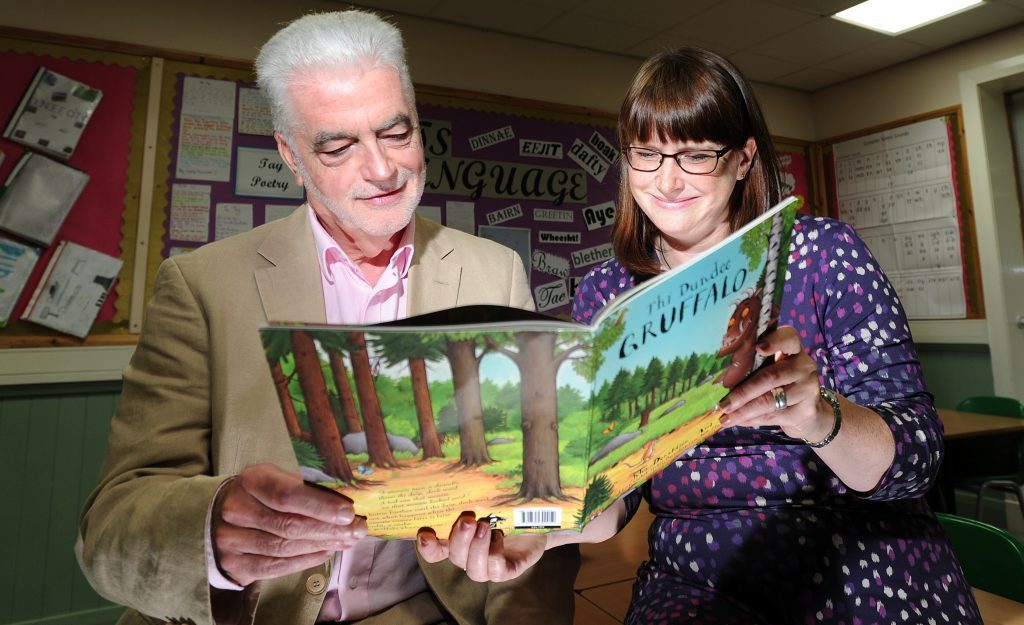

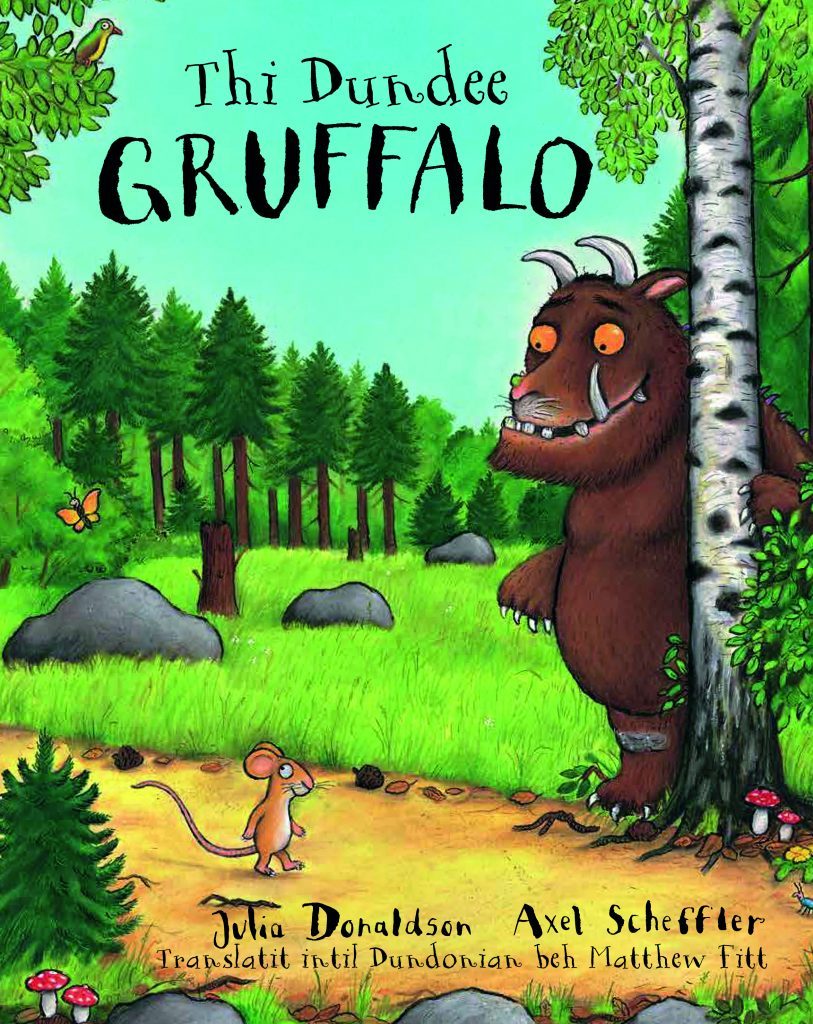

Last year’s release of the Dundee version of award winning children’s book The Gruffalo – translated into Dundonian by Matthew Fitt – is another.

Yet according to Diane Anderson, principal teacher of English at the city’s Morgan Academy, wider Scotland has largely failed to grasp that Dundonese is a rich and beautiful dialect of an ancient language, which captures the beauty and rich cultural heritage of the city.

In the 2011 census, over 1.5 million Scots revealed that the Scots language was an important part of their national identity.

But all too often, Diane reveals, there has been a tendency to “educate out” or be “ashamed” of the “mithir tongue”.

Now, having recently been trained as one of Education Scotland’s Scots language co-ordinators, and ahead of a BBC Scotland radio documentary being aired on Tuesday, Diane tells The Courier that far from being embarrassed about local dialects, the ability to speak bilingual in Scots and English should be a source of great pride.

“The system in general shouldn’t encourage the educating out of Scots,” she says.

“It’s enshrined in the curriculum that Scots is valued and that the language that children bring to school needs to be acknowledged and valued.

“But I think there is a feeling that standard English should be encouraged – that learners will become confused if they speak Scots or that they need to learn proper English first.

“All the research shows that if Scots is your mither tongue you are going to do better in English if your Scots is acknowledged. That goes for any bilingual child whether you are Scots or Polish.

“It’s confusing to pretend that Scots is slang or to pretend that it’s not a viable means of communication. Yet my experience of working in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dundee is that the urban Scots speakers tend to be ashamed of their Scots and to think that it’s not an asset.”

Born in Canada, Diane grew up in Macduff, Aberdeenshire from the age of five, where she was immersed in Scots and the traditional Doric tongue. Her parents, both from farming stock, actively encouraged Scots and it was the lingua franca at home and in the village.

Yet having studied at Aberdeen University and then working in England before her move back north, it’s only relatively recently she’s felt comfortable using Scots in a professional context.

Through the Curriculum for Excellence, she is now helping Dundee pupils realise that they too should be proud of their city’s dialect.

Bairns

But overall, she says, there is still a “job to be done”.

“There are bairns here in Dundee that unconsciously speak Scots all the time,” she says.

“There are children who use Scots because they assume the teacher will not understand them. They’ve almost weaponised Scots as a means of keeping a teacher out of conversation.

“But there are an awful lot of them who will tell you they are not Scots speakers because they are encouraged not to be at home – quite often by Scots speaking parents who don’t have any pride in the fact they are bilingual.”

Diane adds there are a sizeable number of children who speak at least some Scots because it’s a continuum with English. Examples include the use of words like “bairn” or “dreich” in everyday speak.

The relative decline of Scots language is certainly a fascinating one. With the Union of the Crowns in 1603 and subsequent loss of the Scottish Parliament in 1707 – which did all its business in Scots – the official capacity of Scots was lost just at the time when English was becoming codified and spelling was becoming regular, explains Diane.

This helped lead to the rise of dialects as the centralised influence of Scots language waned.

But the history of the Dundee dialect is probably also rooted in the ethnic history of the city.

Diane says one myth is that the hard ‘eh’ sound was because of the jute mills. But the reality was that because of the din of the mill machinery, workers wouldn’t have heard a thing and had to use sign language.

She says a more likely explanation is the ethnic mix of immigrants from Ireland and how that melded and came together to influence language.

Before the Tay bridges, Dundee was also a great example of a relatively insular city contained by geography – and this too impacted on its vernacular.

She adds: “You can throw a blanket over the city and you can draw a distinct line around where people say ‘peh’ rather than pie. That’s brilliant. That should be celebrated. That makes Dundee unique.”

However, those who frown upon Scots language, she says, often tend to be monolingual English speakers who somehow think they are “superior”.

“It actually beggars belief,” adds Diane. “It is perpetuated by people looking down on it, thinking of it as slang. Orey is a word that’s used in Dundee to express the way some people speak. But Dundonian Scots is not orey. It’s rich and beautiful.”

Scottish set texts have been taught in schools for years, and that is being developed further through the new curriculum.

Burns, another fixture of Scottish classrooms, is the only poet in the world whose birthday is celebrated internationally. His creation Auld Lang Syne is the second most recognised song in the western world.

Yet it’s essential, Diane says, for Scots to understand what the words actually mean.

BBC broadcaster and Scots language expert Billy Kay agrees. He says Scots is central to our identity but warns if we can’t read our own history and poetry, we become foreign to our own culture – and there’s a danger there’s not much left of Scotland as a nation.

But whilst there’s no doubt Scots language is intrinsic to national identity, Diane doesn’t think it should be confused with nationalism.

“I don’t think being a Scots speaker makes you any more likely to be a nationalist or any less likely to be a nationalist,” she says.

“I don’t think the two are interlinked at all – although people do try to link them because it seems like an easy thing to do.”

- The Scots Tongue is broadcast on BBC Radio Scotland at 1.32pm on Tuesday September 27. It’s repeated on Sunday October 2 at 7.04am and available for 30 days on the iPlayer