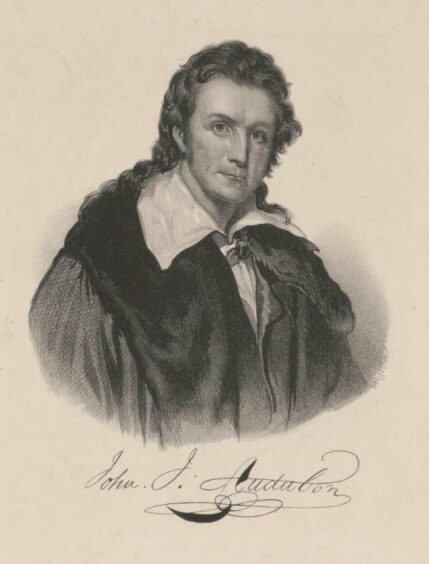

He is celebrated as the quintessential American woodsman, adventurer and naturalist, who identified over 20 species new to science.

Living life on the American frontier, John James Audubon’s paintings of the natural world are some of the most famous in the history of art and natural sciences, and his portrait hangs in the White House.

However, Audubon’s story is full of contradiction and controversy mixing the legend that built up around him during the early 19th century with the more complex, problematic realities of the times.

Controversies

Audubon profited from the ownership of enslaved people and showed disdain towards the abolitionist movement, aspects of his story which, until recently, have been overlooked.

However, his scientific standing has also been disputed, with accusations of completely fabricating some bird species and making errors in the identification of others.

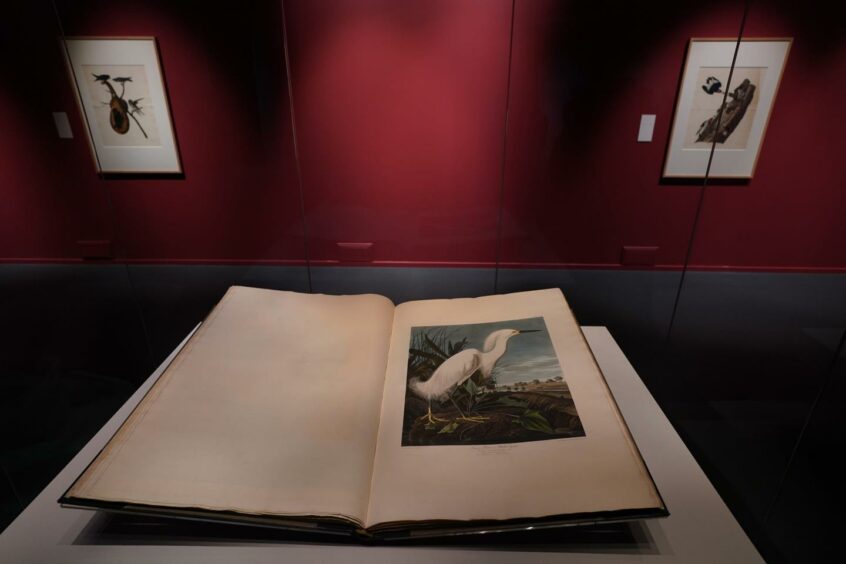

A new exhibition opening at the National Museum of Scotland (NMS) in Edinburgh examines the artistry and legacy of Audubon’s work, as featured in one of the world’s rarest, most coveted and biggest books.

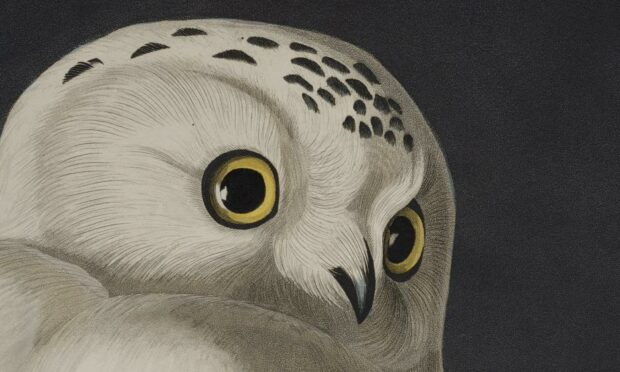

Published as a series between 1827 and 1838, The Birds of America by John James Audubon (1785-1851) was a landmark work which achieved international renown due to the epic scale of the project and the book’s spectacular, life-sized ornithological illustrations.

The exhibition, Audubon’s Birds of America, which runs at the NMS from February 12 to May 8, showcases 46 unbound prints from National Museums Scotland’s collection, most of which have never been on display before.

It also features a rare bound volume of the book, on loan from the Mitchell Library.

Unique opportunity

In an interview with The Courier, curator Mark Glancy described the exhibition as a “unique opportunity” to see so much of Audubon’s work in one place.

The four volumes which make up The Birds of America consist of 435 hand-coloured prints. The book was the culmination of Audubon’s ambition to paint every bird species in North America, and is celebrated for its extraordinarily animated, dramatic and detailed illustrations.

However, in order to accommodate life-sized birds, the book had to be printed on paper which was almost one metre long.

Even then, some larger species had to be posed in contorted positions in order to fit them onto the page.

While his predecessors and contemporaries illustrated birds looking stiff and unnatural, Audubon was pioneering in his depiction of scenes from nature, pinning birds into realistic poses he had observed in life and painting on the spot.

“Birds of America is one of the most beautiful and famous books in the world, and the story of its creation is extraordinary,” says Mr Glancy, who is in charge of the library at the NMS.

“Most people have only seen digital copies, so this lavish exhibition gives visitors a once-in-a generation opportunity to view so many of the prints together in one place and appreciate the scale and ambition of Audubon’s “Great Work”.

“Audubon was, and remains, a contradictory and controversial figure and the exhibition will examine the myths and the reality behind this American icon.”

Who was John James Audubon?

Born in 1875 in Les Cayes in the French colony of Saint-Dominigue (now Haiti) on his father’s sugarcane plantation, Jean Audubon Jnr was the son of Lieutenant Jean Audubon, a French naval officer from the south of Brittany, and his mistress Jeanne Rabine, a 27-year-old chambermaid from Les Touches.

Audubon Snr had been imprisoned by Britain during the American Revolution and later helped the American cause.

The story goes that following Jeanne Rabin’s death, Audubon Snr renewed his relationship with Sanitte Bouffard and had a daughter by her, named Muguet. Bouffard also took care of the infant boy Jean.

Due to slave unrest in the Caribbean, however, Audubon Snr sold part of his plantation in Saint-Domingue and purchased a farm near Philadelphia, before returning to France where young Jean, and his French wife, joined him.

From his earliest days, young Audubon had an affinity for birds and loved roaming in the woods.

This continued, and, after an unsuccessful attempt by his father to make a seaman of him, 18-year-old Jean was sent to the United States by his father to avoid conscription in the Napoleonic Wars.

Set up in a business partnership by his father to pursue lead mining, his later merchant business moved west and in 1808 trading was adversely affected by President Jefferson’s embargo on British trade.

American citizenship

Audubon became an American citizen in 1812 following Congress’ declaration of war against Britain.

Between 1812 and the Panic of 1819, he bought land and slaves, founded a flour mill and enjoyed life with his growing family. However, after 1819, he went bankrupt and was jailed for debt.

Earning some money from portraits, he travelled to the southern states in 1820 to search for ornithological specimens.

Finding time to roam and paint in the woods, he adopted new painting techniques and, on realising the scale of his ornithological art ambitions and need to travel, called his future work The Birds of America.

“What makes Birds of America special is predominately artistic in that it’s the way that he portrayed birds,” says Mr Glancy.

“He showed them as not only life sized but life like as well.

“He was trying wherever possible to draw from nature.

“He was spending a lot of time observing birds before he would paint them.

“Wherever possible he would paint them in the wild as well. So he had to do it quite quickly before they lost their plumage colours.

“He also, in the arts side, tried to represent birds of different positions. You could see the plumage from underneath and maybe have males, females and juveniles because the colours might be slightly different. He tried to portray as much as possible of the birds.”

Discoveries and science

Mr Glancy says Audubon was also a field naturalist.

He identified and named new species. Some of those have since been re-assigned, thanks to advances in technology, better photography and DNA science.

There’s also, however, some controversy around his science.

There’s a general consensus that he fabricated at least one species which is in the exhibition – The Bird of Washington, the largest eagle in North America.

“As well as the misidentification, he was also working at a time when he didn’t really fit into the profile of a naturalist,” adds Mr Glancy.

“Most of them were quite wealthy, and he was anything but.

“Basically The Birds of America could only be published because he would get subscriptions and that would pay for the next set being issued.

“So even though, by this time, he was a failed businessman and bankrupt, when it came to Birds of America he was quite a shrewd businessman.”

Conservation

The exhibition touches on controversial legacies such as slavery, which he didn’t seem to question.

There are contradictions, however, because some of his patrons were abolitionists.

“He was also quite important for conservation as well,” adds Glancy.

“He didn’t necessarily practice it himself. He shot birds to study them and paint them and give exhibits to museums.

“But he did write a lot about the impact man was having on the natural environment –forests disappearing, agriculture, getting rid of the natural environment for birds.

“And he did talk about some species like the Carolina Parakeet. He could see numbers decreasing and about 80 years later, it was then extinct. The only indigenous parrot in North America.”

Shrewd businessman

Audubon’s shrewdness as a businessman was reflected in the way he marketed himself as the archetypal American woodsman and frontiersman.

He learned a lot of woodcraft from indigenous people, and when he was naming or writing about birds, would add “local knowledge”.

While his woodsman character was seen as “something as a plus” when he was in Europe, however, it wasn’t such an asset in America where he was seen as more of a “country bumpkin and uneducated”.

Links with Edinburgh

The exhibition explores Audubon’s ironic inability to get The Birds of America published in America.

It looks at Audubon’s links with the scientific and artistic community in late-Enlightenment Edinburgh, where the process of publishing the book began.

He visited Edinburgh six times, including research visits to what is now the National Museum of Scotland itself.

“We do have the back story of that,” adds Mr Glancy.

“He went to Philadelphia which was scientific and printing centre at the time in 1824, and was basically rejected. So he came to Europe to find an engraver to print.

“He wanted to come to Edinburgh.

“In actual fact, he was coming for five days or a week, and he stayed five months when Birds of America started to print.

“William Lizars printed the first plate. He was accepted into scientific societies like the Royal Society of Edinburgh and Aviarian Natural History Society.

“He had an exhibition at what is now the RSA (Royal Scottish Academy) at The Mound. That almost kick started Birds of America.

“Unfortunately Lizars’ colourists went on strike after the first 10 were done, then he had to start again.

“The remainder were printed in London. But he kept coming back to Edinburgh.”

Mr Glancy explained that, to avoid copyright laws, The Birds of America didn’t have any text other than the legend on the plate to tell what the bird was.

Audubon then published an accompanying five volume book in Edinburgh, which was the biographies of all the birds.

“After that initial five month visit, he came back five times. Spending almost the equivalent of three years in the city. He loved it. He wrote about it a lot how much he loved the city.”

Conservation

The exhibition brings the story up to the present day, looking at the conservation status of some of the species featured in The Birds of America.

But how significant is the book from an ornithological perspective in reflecting today’s world?

“There are differences,” says Mr Glancy.

“He always wanted to get beyond the Rockies and he never did. There’s a whole west coast of America that he never discovered, although he probably travelled to more of America than anywhere else at that time.

“If he couldn’t see the birds themselves, he would end up getting bird skins sent back from expeditions beyond the Rockies so that he could write about them and draw them.

“There were originally going to be 400 plates but ended up being 435.

“Normally he had one species per plate but when he got to the end he was desperate and sometimes put multiple on plates. A lot of what he wrote about is still accurate.”

The exhibition includes the first five plates as subscribers would have received them, and one of the highlights is having a bound volume on display as well, alongside specimens to show scale.

It was 11 years from start to finish if you were a subscriber,” he adds. “So you basically had to be rich or an institution to stick with that!”

*Audubon’s Birds of America, February 12 to May 8, 2022, National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh, https://www.nms.ac.uk/