High streets make a huge contribution to the country’s economy, society and culture. But they are no longer just about retail and new ways are having to be found to make them vibrant. In the first of a five-part series looking at the changing face of Courier Country High Streets, Michael Alexander speaks to some of the national experts looking to unlock our towns’ potential.

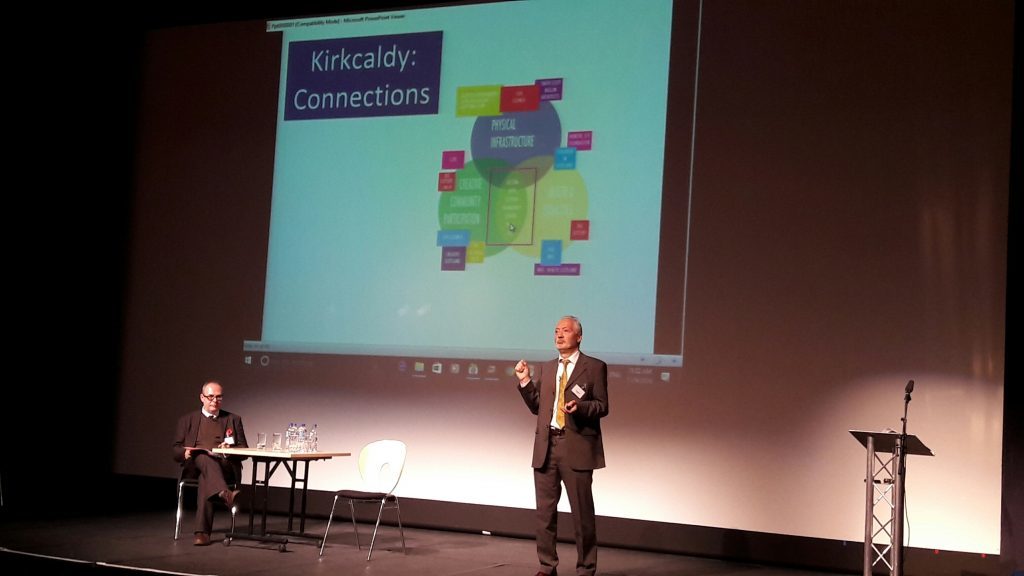

When Fife-based broadcaster Lesley Riddoch opened Scotland’s Towns Conference in Kirkcaldy on November 9, it was just hours after Donald Trump had been declared president elect of the USA – and many of the delegates were reeling.

The glitz of US politics might have seemed a world away from the gathering of government representatives, international experts and community groups meeting at the Adam Smith Theatre.

But Ms Riddoch said the shock Trump result, and the recent decision of Britain to leave the European Union, were incredibly relevant as discussions got going to promote towns in Scotland.

“If you look both at the Brexit vote and the vote (for Trump),” she said: “it was the cities that voted for the liberal consensus, and it was the villages, the rural areas, and perhaps you could say the towns – the smaller areas that feel a bit left out from the consensus – that decided to do something quite rash.

-

Read more on Our Changing High Streets here

“I spend an awful lot of my time trying to put right the perception that most Scots live in cities. They don’t. They live in towns. They are the centre of most lives in Scotland.

“So how they operate, how vibrant they are, how inclusive, all these things determine how Scotland feels about itself – how successful it is, how fair it is.”

There’s no doubt that our town centres are changing and continue to change. The number of boarded up shops following the 2008 financial crash, the growing number of charity shops and the rise of vaping shops have shown that.

But what challenges are facing our high streets, and what efforts are being made to improve them?

Well, for a start, towns are no longer just about retail, according to Scotland’s Towns Partnership chief officer Phil Prentice. They aspire to be vibrant hubs where we enjoy culture and leisure, socialise, work, live, do business and set up new enterprise.

Take Fife. The council’s depute leader Councillor Lesley Laird draws attention to the efforts that have gone in to improving Fife’s four main towns – Dunfermline, Kirkcaldy, Glenrothes and St Andrews – all with different challenges.

The Kingdom has 32 town centres in total, all with their own individual personalities and each is loved by their communities.

“We are all familiar with the challenges. For example, big stores leaving Kirkcaldy – Tesco, BHS – the problems with out of town shopping; competition from online shopping; the contentious issue of car parking; budget cuts and lack of finance, and finance and domestic rates,” says Councillor Laird.

But she also welcomes the forthcoming review of rates by the Scottish Government.

“The pre-recession business rates review has left our high streets struggling,” she continues.

“The forthcoming review is to be very much welcomed and the business community is looking forward to what the outcome of that will be.

“But I suppose the question that remains in my mind is will these opportunities result in some radical change? Will some radical thinking happen to line up all the economic levers, and deliver inclusive and sustainable economic growth?

“It’s not just about rates. It’s actually a broader question about how do we use all these economic levers that we have in our tool box?”

Councillor Laird has particular concerns about the subsidies used to help charity shops and whether these benefit the wider town centre economies?

“I’ve nothing against charities, “she adds: “But are we making best use of that subsidy?

“In 2010 the subsidy to the charity sector in Fife alone was £2.75 million.

“If you look at the subsidy to the charity sector now, it’s £9.2 million. And yet the number of businesses those charities are taking that support from has dropped from 687 to 642. So in other words there are less charities but their presence has become more pronounced.

“That’s prompted me to ask in real terms, what’s the return in investment in terms of this £9m investment? What long term economic benefit has been achieved by all of this investment over these number of years? And has it really been best value in terms of delivering inclusive growth and sustainable employment?

“Whilst there is clearly benefit that the high street shops are not left empty, and the charity shops have certainly a place, has this subsidy in the long term perhaps distorted the quality of the town centre and the shopping experience?

“And with the recent changes in non-domestic rates, are we now likely to see similar trends emerging in our industrial spaces?”

Professor Leigh Sparks, chairman of Scotland’s Towns Partnership and an adviser to the Scottish Government, says the Scottish Government’s decision to respond to the crisis in town centres four years ago was a “milestone”.

However, the really hard work, he says, is done by people in communities up and down the country.

“Scotland’s Towns Partnership has tried to redirect the neglect of the last 50 years,” he says.

“There’s not a quick process but we feel we have made a difference and will continue to do so on behalf of one of Scotland’s best assets – its towns and their people.

“We need to make sure our towns are places where people want to live, work and play, and they have the leadership they now deserve.”

Scotland’s Local Government Minister Kevin Stewart, a former depute leader of Aberdeen City Council, says shoppers have “more choices” than ever before.

“To attract people and investment,” he says, “town centres have to offer better choices in lots of ways – how pleasant they are to be in and in terms of access.

“We are living in a time of fast paced change economically and socially. Town centres need to keep pace with changing habits and lifestyles.”

Mr Stewart says this had been recognised by the Scottish Government with a new narrative seeing town centres as being central to community life, places for people to live, work and of course socialise.

More work had to be done, however, with an important part of this about “giving power back to the people.”

“We are at the start of that journey,” he continues.

“Community trusts and community councils have a large part to play. Local authorities themselves have a responsibility for economic development in their areas. I think more and more local authorities are doing the right thing by their town centres.”

Mr Stewart also acknowledges there needs to be better digital connectivity for town centres to attract business.

“Obviously we gave a manifesto commitment to create a situation where there is broadband access right across Scotland,” adds Mr Stewart.

“And beyond that we want to ensure as technology develops into 4G and 5G that we benefit here. Unfortunately a lot of that still lies at UK government level.

“We will use every power at our disposal. What we need the government to recognise is that it is unfair that any part of the UK misses out on the technology because at the end of the day we know that in today’s world it is absolutely vital to get access to superfast broadband.”

Dr Steve Millington, director of the Institute of Place Management at Manchester Metropolitan University, describes town centres as “dynamic entities.”

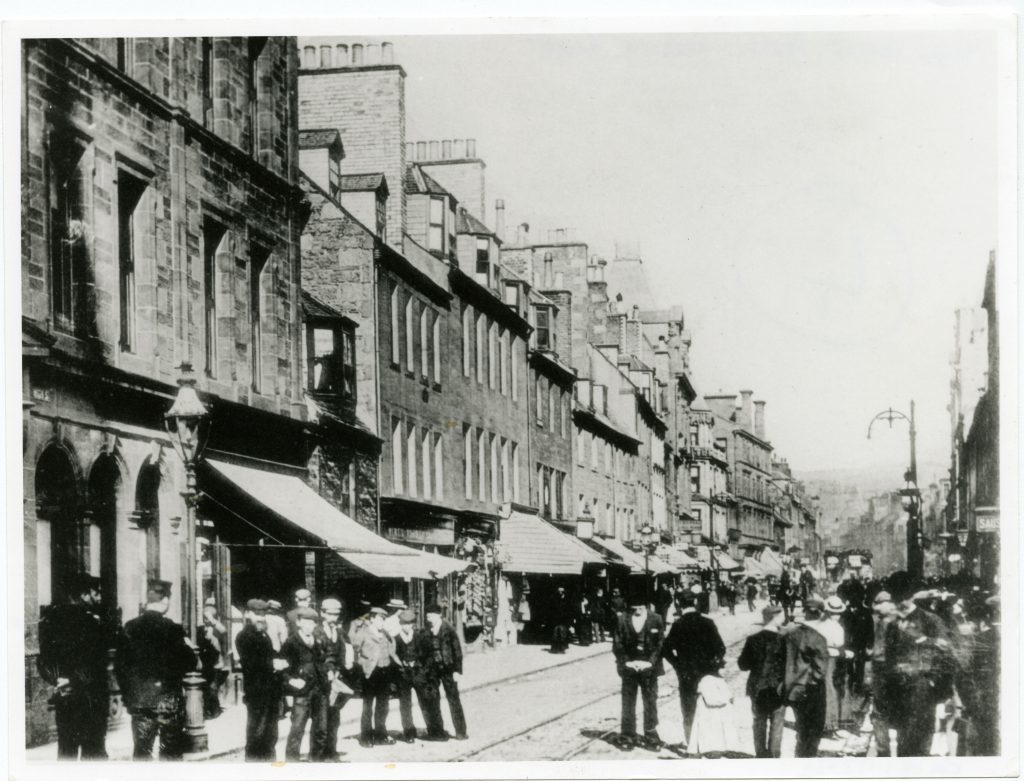

“We might have nostalgic views of town centres being full of people, independent shops and Woolworth and all that,” he says.

“But high streets are constantly adapting, responding to new technologies and business models.

“That said, recent structural changes are proving highly disruptive. Over the past 15 years or so retail spend on high streets has declined to less than 40%.

“The other structural issue is that UK shoppers like to drive. This is self-fulfilling.

“They are using their cars, they want to park somewhere which builds congestion into town centres.

“So what do they do? They go out of town and that’s reflected in the figures that show the amount of retail space.

“Town centres in the decade up to 2011 lost 46 million square feet of retail space whilst out of town retail grew by 50 million square feet. So there’s this relationship between retail space and location.

“In itself this brings an inclusivity issue in terms of affordability and mobility.

“If you don’t have a car how do you access the services?”

Dr Millington says one reason for out-of-town development was that the UK traditionally has a fairly laissez faire planning system compared to Europe leading to urban sprawl and other counter-urbanising trends.

“This is driving people out of town, often to where parking is free, leaving an abundance and over-supply of retail space in the centres.”

Another significant factor is that the UK has the world’s best internet shoppers.

“Town centres are traditional meeting points where groups can mix and share a sense of identity,” he concludes.

“Traditionally they are at the heart of communities. Restoring vibrancy in this context is a major challenge.

“There are some structural factors you cannot control. For example, the change of presidency in the US may have an impact on the UK economy. We can’t do much about that at this stage as a town.

“Structure and layout of a town are certain givens too. We have to live with them.”

Examples of “low hanging fruit”, however, would include the marketing of a town.

“Off the peg prescriptive solutions do not work – answers must be local!” he adds.

“Just because something works in one place, does not mean it will work somewhere else.”

Andy Milne, chief executive of Scotland’s Regeneration Network SURF, says it’s wrong to blame disadvantaged communities for being run down as there were often external economic factors at work.

What was key, however, was realising the potential of these places and making creative connections with wider networks.

“Where we find ourselves is not some act of God,” he says of our town centres.

“We are in Kirkcaldy, the place of Adam Smith, the invisible hand of the market.

“We are still in one of the world’s richest countries but there tends to be a pooling of resources.

“Things tend to be invested in places where things are already working well. Not the smaller towns or where there is disadvantage.

“That is a decision that we make, and my view is we need to make more conscious decisions to overcome these forces of the market drawing towards the centre, otherwise we will continue to see more problems which we will struggle to solve.”

Mr Milne says the Gallatown in Kirkcaldy is an example of trying to link in to the wider regeneration of Kirkcaldy.

He says there is a strong case, however, for restructuring local government and bringing more meaningful power to grassroots level.

“One of the struggles we have is that in Scotland we are labouring against having a dysfunctional representative structure,” he says.

“Our local authorities are working really really hard in really difficult conditions, but they are just too big to be able to pick stuff up and make those connections.

“We need to look at re-balancing our investment in these areas.”