How pushy should parents be? As Judy Murray claims British children should be less mollycoddled, Michael Alexander investigates.

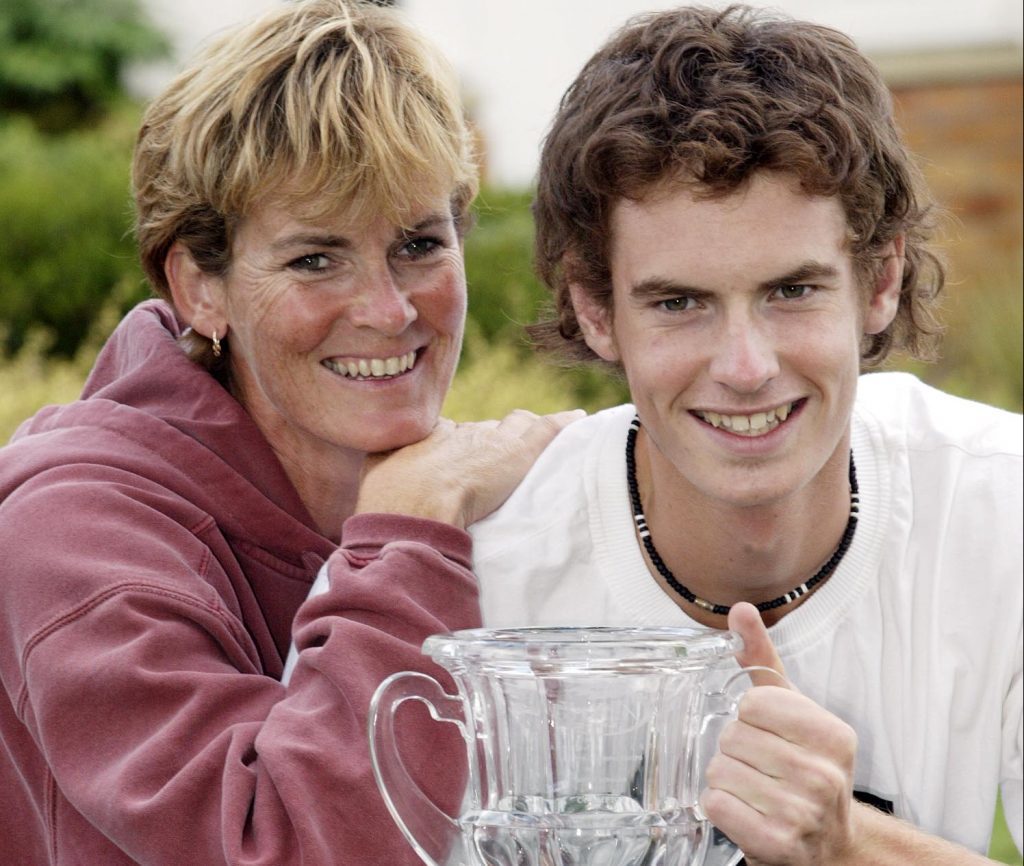

She’s one of the best known mums in the UK, with two of Scotland’s greatest ever sportsmen for sons, so when Judy Murray speaks out on parenting skills, people tend to listen – even if they don’t always agree.

The 57-year-old from Dunblane sparked controversy this week when she suggested today’s children live overly cushy lives and could benefit from a tougher upbringing.

Judy, mother of tennis stars Andy and Jamie Murray, reportedly criticised mums and dads for pampering offspring who should be taken out their “comfort zone”.

“Life is too easy for children,”she said. “They have gadgets to solve their problems, be it a calculator or a Google map.

“We mustn’t be afraid to put them in situations where they have to get out of trouble.”

She’s not a lone voice. According to child psychologists, we shouldn’t be surprised at the trends as a generation of so-called “snowplough” parents have pampered their children so much that they are driving a mental health epidemic among today’s teenagers.

Leading Australian child psychologist Dr Michael Carr-Gregg said many Generation X parents (those born between the mid-1960s and early 1980s) had made their children’s lives so easy that the kids were left with no way to handle problems or overcome obstacles on their own.

The pampering is thought to be a guilt-trip reaction by many working parents who feel they don’t spend enough quality time with their offspring.

Others are more forgiving, acknowledging the additional pressures that modern life puts on youngsters.

Mumsnet.com editor, Kate Williams told The Courier: “Everyone thinks ‘kids today’ have it easier than they did – in fact, it’s probably the surest sign that you’re no longer young yourself. “There’s no doubt that technology and creature comforts make some things easier, but they also make some things harder.

“No previous generation has had to deal with cyber-bullying, or the always-on social culture.

“Older children are under a lot of pressure to achieve exam grades, university places and good jobs, and they know that they’re competing not just against British children but against their peers from all over the world. But then, Judy Murray’s sons know a thing or two about that.”

Cupar-based staff nurse Marianne Berghuis, 42, who volunteers as a cycle training assistant for Bikeability and as a Beavers section assistant with her local Scout Association, says the solution is not so much about being “tougher” with children.

In her view, it’s about finding a balance and switching off the tech more often and spending time together doing other things. That should go for the adults as well, she insists.

Marianne, a mother of two boys, told The Courier: “Some children are too over scheduled with after-school activities that they don’t have time to engage with more family activities or time to amuse themselves or become bored.

“Some children seem to be constantly connected and bombarded with media exposure e.g. TV, iPads, computers, smart phones etc.

“Some kids have a modern day addiction to ‘tech’. Limiting screen time is proven to improve sleep, performance at school and have a positive effect on behaviour.

“Children are sometimes not put in situations where they could get into ‘trouble’ and they are shielded from potential dangers but they need some exposure to learn from this.”

Two contrasting reports published last week have certainly focused debate on the ability of “pampered” children to fend for themselves – and ultimately attain their potential – in the ‘real world’.

The National Child Development Study, published by researchers at Edinburgh and Glasgow universities, suggested that people who were in the Scouts or Guides in childhood have better mental health in later life.

Analysis of a study of 10,000 people, born in November 1958, found ex-members were 15% less likely than other adults to suffer anxiety or mood disorders at the age of 50.

Researchers believe it could be the lessons in resilience and resolve that such organisations offer that has a lasting positive impact.

Bill Stevenson, director, of The Boys’ Brigade Scotland, said: “Researchers found programmes which help young people with skills such as teamwork, outdoor exploration and self-reliance can provide lifelong benefits.”

By contrast, however, a report from the NSPCC gave a snapshot of how the modern world – and exposure to it through 24-hour media – can have a detrimental impact on British children’s mental health.

Children as young as nine are contacting Childline petrified about terror attacks happening on their own doorstep.

Since November 2015, the NSPCC’s round-the-clock service has handled 660 counselling sessions about terrorism, with children mentioning panic attacks, anxiety, insomnia, and nightmares about terror attacks.

Counsellors at Scotland’s two Childline bases in Aberdeen and Glasgow have handled 111 counselling session from children across the UK in that time.

Returning to sport, Peter Davidson, chief executive of the Links Park Community Trust in Montrose said: “For me, clearly, in order for children to truly excel at a particular activity, they are going to have to sacrifice some of life’s little luxuries, and lead a lifestyle that gives them the best possible opportunity physically to succeed.

“The biggest problem we need to address, in my opinion, is the drop-out rate from sport, particularly as kids approach their teens.

“If children are proficient in something, they stick at it, so we need to develop a sporting culture that instils a desire to improve.

“I think we are guilty at times of referring to children as ‘elite’ from too young an age. They then start to believe they are world beaters already, and lose the urge to improve and get better.

“Don’t praise the winning free-kick, praise the two hours extra spent practicing them.

“Andy Murray moved abroad and trained alongside some of the best performers in the world I his particular sport, so he saw, first hand, the improvements he had to make to reach the top.

“We shouldn’t lose sight of the role of sport though, in developing skills that relate to life, learning and work. Develop the person first, the player second, and they may then just have the right attitude to succeed should they demonstrate and work at improving the necessary skill-set.

“Too much pressure though, towards results, as opposed to effort, can contribute to the drop-out rate. It has to be fun.”

But be warned! A balance clearly has to be struck with Andy Murray himself reportedly saying in an interview several years ago: “Being pushy is the worst thing a parent can be – if you push your children, you stop them enjoying whatever it is they’re good at!”