Michael Alexander investigates the hundreds of shipwrecks that can be found in the seas off Courier Country.

Of the three million shipwrecks estimated by the United Nations to rest on the ocean floor, approximately 40,000 of them can be found in UK waters ranging from 10,000 year-old dug-out canoes through to modern day 21st century wrecks.

Not surprisingly mainland Scotland’s 6000 miles of coastline are peppered with many of these vessels, ranging from ships trashed on rocks long before lighthouses, to warships sunk during the dark days of the First and Second World Wars.

Today, many of these wrecks are of interest to divers, marine archaeologists and treasure hunters alike.

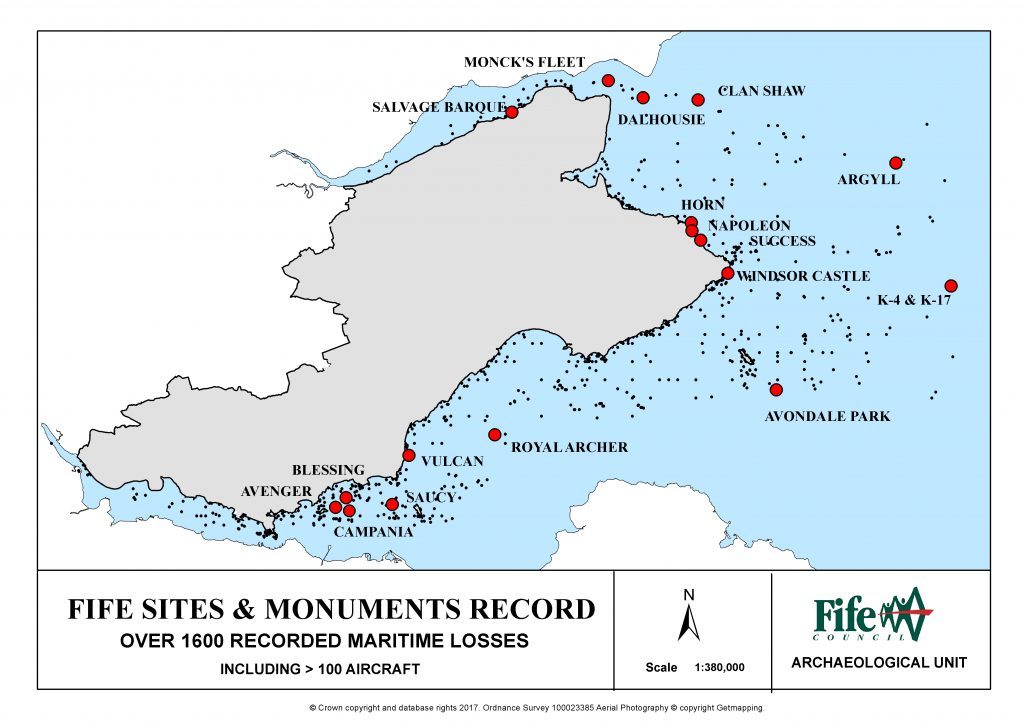

And some of the most interesting sites are found around the Fife and Tayside coast where everything from royal treasure ships, tragic fishing trawlers and sunken submarines provide a fascinating, if not sobering, insight into the nation’s ancient links with the sea.

Mark Blyth, 54, proprietor of the five-star Dive Bunker dive school in Burntisland, has been diving in the Firth of Forth for 35 years.

Of the estimated 500 ship wrecks in the murky waters of the Forth, he has dived hundreds of times on around 30 of them.

Highlights include finding the bell of the Vulcan, located off Kirkcaldy, and the bell of the Royal Archer – which lies in 30 metres of water off Methil after being bombed in an air raid on June 3, 1941.

He also discovered an almost intact Grumman Avenger Second World War-era torpedo-bomber aircraft lying in just 14 metres of water a mile offshore from Aberdour.

Engine failure forced the aircraft to ditch into icy waters on December 17, 1945, during a training exercise from 785 Squadron in Crail.

His favourite wreck for “sheer scale”, however, is the HMS Campania.

The Glasgow-built former Cunard Liner, which set speed records for its Liverpool to New York crossings in 1893 and 1894, was converted into an aircraft carrier by the Royal Navy in the First World War – becoming the first navy vessel ever to launch aircraft whilst underway.

She had avoided enemy attacks throughout the war.

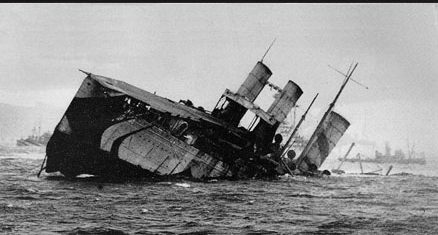

However, just four days before the end of hostilities, she accidentally sank off Burntisland after dragging her anchor during strong winds.

She collided with the nearby battleship Revenge and a hole was torn up in the Campania’s hull, sending all 18,000 tons of her to the bottom within two hours. The only saving grace was that no one was killed or injured.

“When she sank her masts stuck out of the water – she was so big – so the navy blew her up later to reduce the navigation hazard,” explains Mark.

“”The sheer scale of her at 550 feet long is still amazing though. You swim up by the gun which appears frozen in time.”

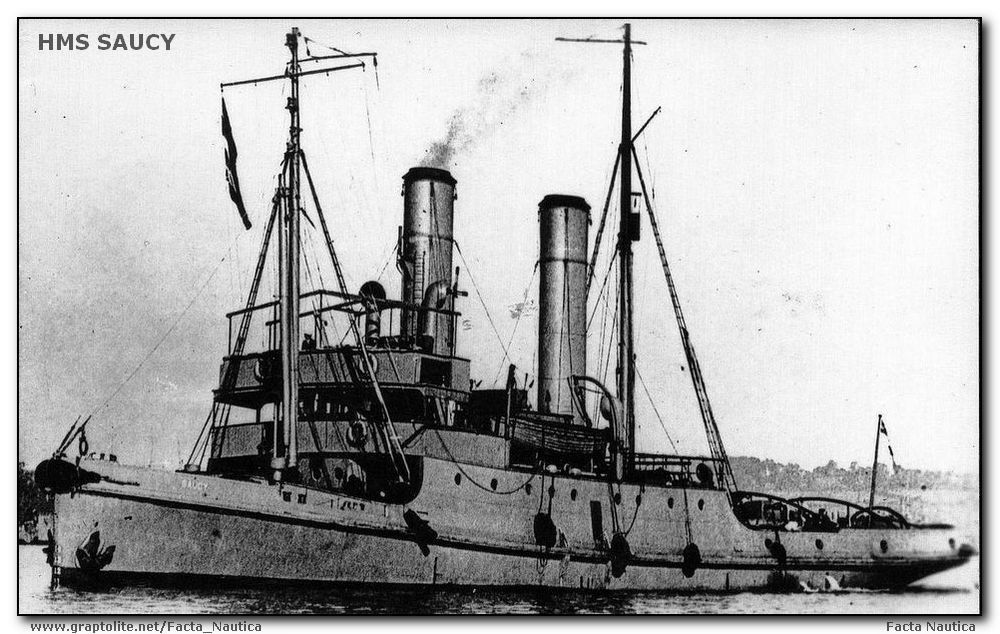

The most intact wreck in the Forth is the 579-ton HMS Saucy, a former tug which now lies in 17 metres of water after being sunk by a German mine on September 4, 1940. All 28 crew lost their lives that day including 18 men from the small Cornish town of Brixham.

Mark describes this dive as a particularly “moving experience”.

The deeper waters around the May Isle, beyond the outer reaches of the estuary, are also littered with wrecks.

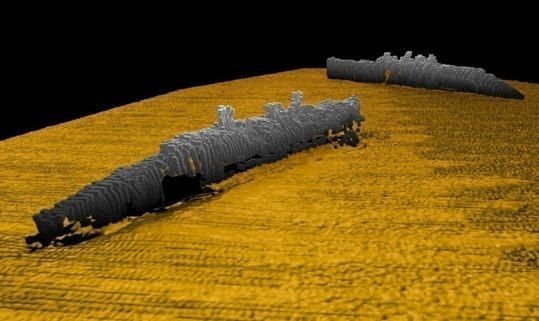

They include the remains of the First World War K-class submarines lost during the so-called ‘Battle of the May Isle’ – a disastrous series of accidents that occurred during a Royal Navy exercise on the night of January 31/February 1, 1918.

Five collisions occurred between eight vessels. Two submarines were lost and three other submarines and a light cruiser were damaged, leading to the loss of 104 men.

Nearby, 1.5 miles south east of the May Isle, the remains of another tragic vessel -the S.S. Avondale Park – can be found.

Going down with the Norwegian Sneland 1, she was the last merchant ship sunk by a German U-Boat just minutes before the official end of the Second World War.

Other wrecks, however, simply remain the stuff of legend with little evidence that they actually exist.

On July 10 1633 a timber baggage vessel, loaded with the personal possessions and riches of King Charles I, foundered and sank to the bottom of the Forth, shortly after leaving Burntisland for Leith.

The sinking of the Blessing also claimed the lives of 35 of the king’s domestic servants and personal entourage.

The boat was thought to be carrying a hoard of treasure worth £100,000 – a figure equivalent to approximately 20% of all the money circulating in Scotland at that time. Yet, despite investigations, no firm evidence of the wreck’s existence has yet been found.

Another legend that has captured the imagination relates to General Monck and his forces who in September 1651, under the orders of Oliver Cromwell, sacked the city of Dundee and burned it to the ground.

Hundreds of the town’s inhabitants were massacred, and their possessions looted.

As 60 ships from Dundee Harbour were commandeered and filled with around 200,000 stolen gold coins, the story goes they floundered in a storm near the mouth of the Tay and sunk. But again, no evidence of the treasure, estimated to be worth up to £12 billion, has been located.

Internationally-renowned marine archaeologist and Fife Ambassador Neil Cunningham Dobson, 60, from St Andrews, played a key role in the recent discovery and salvage of the world’s deepest and largest precious metal recovery from the shipwrecks of the SS Gairsoppa and SS Mantola in the North Atlantic.

The former St Andrews Coastguard member said it’s possible the Tay wrecks exist, because the sacking of Dundee did happen.

However, he suspects that the gold would have been put on a bigger ship and that it would have made it through the storm.

If the blood-tainted treasure does lie beneath the Tay, he does not believe it will ever be located or salvaged because the cost and practicalities of shifting thousands of tonnes of sand would make the project unviable.

“From the 3000-year-old Carpow log boat found near Abernethy, to the remains of the Middlesborough barque lifting barge at Wormit used to lift the train from the Tay Rail Bridge disaster out of the water, the Tay is no stranger to wrecks,” says Mr Dobson.

“Round into St Andrew Bay, and between 1800 and the present day, there were 233 shipping losses alone between the River Eden and Anstruther.

“They range from the iron paddle steamer Windsor Castle grounded on rocks east of Crail in 1844 and the whaler Horn that became stuck hard and fast on the Babbert Stane rock in 1848.

“The last merchant vessel incident in St Andrews Bay was in 1987 when the Russian motor vessel Znamy Oktyabrya that was at anchor was driven ashore at Kinkell Ness close to the caravan site in a bad storm.

“Luckily, she was able to refloat the next day and make it to a shipyard for repairs.

“But go even further back, and there must have been plenty Viking ships wrecked on the Fife coast. The Romans used to sail from the Forth to the Tay, and it was the Roman geographer Ptolemy who used to warn Romans not to sail up the River Eden by mistake!”

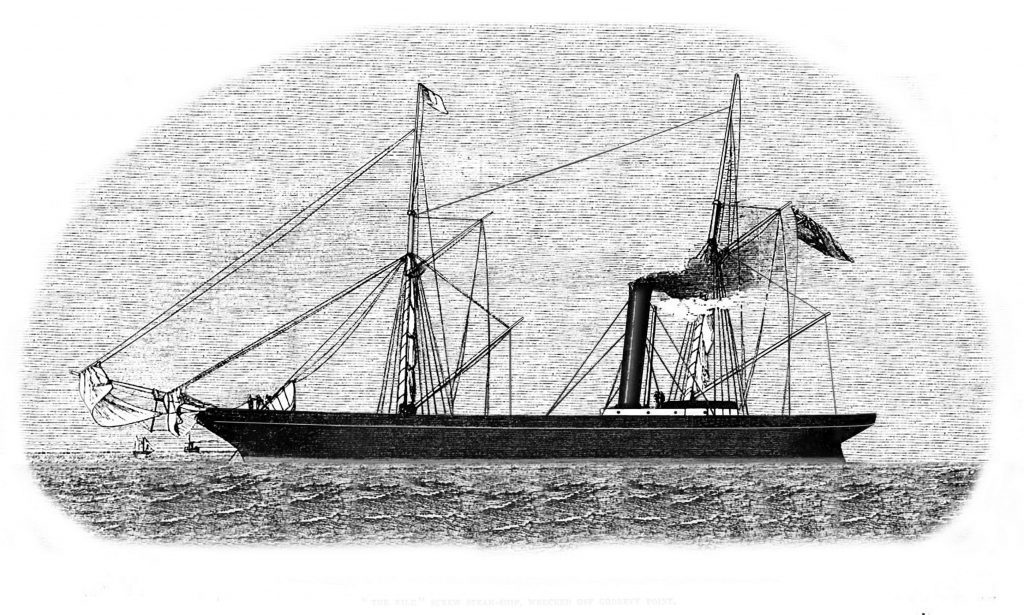

Dundee historian Dr Andrew Jeffrey said that unlike tragedies such as the loss of the lifeboat Mona or the Tay Bridge disaster, the loss of the Dalhousie steam ship, that sailed into oblivion with the loss of 34 men, women and children on a run from Newcastle to Dundee in 1864, has been largely forgotten.

She was heading back to Dundee and was battling a force-nine gale from the east when her engines failed and she went down in 30 feet of water off Tentsmuir, where wreckage and bodies were strewn along the beach.

All hands were lost including Captain Glenny, who is buried in Dundee’s Western Cemetery, and Tom Bisset, a ship’s engineer, from Broughty Ferry.

Other tragedies he mentions include the loss of the Swedish brig Napoleon driven ashore and lost with all hands at Boarhills on October 23, 1864, and HMS Success that ran aground below Cambo House, Kingsbarns, on December 27, 1914.

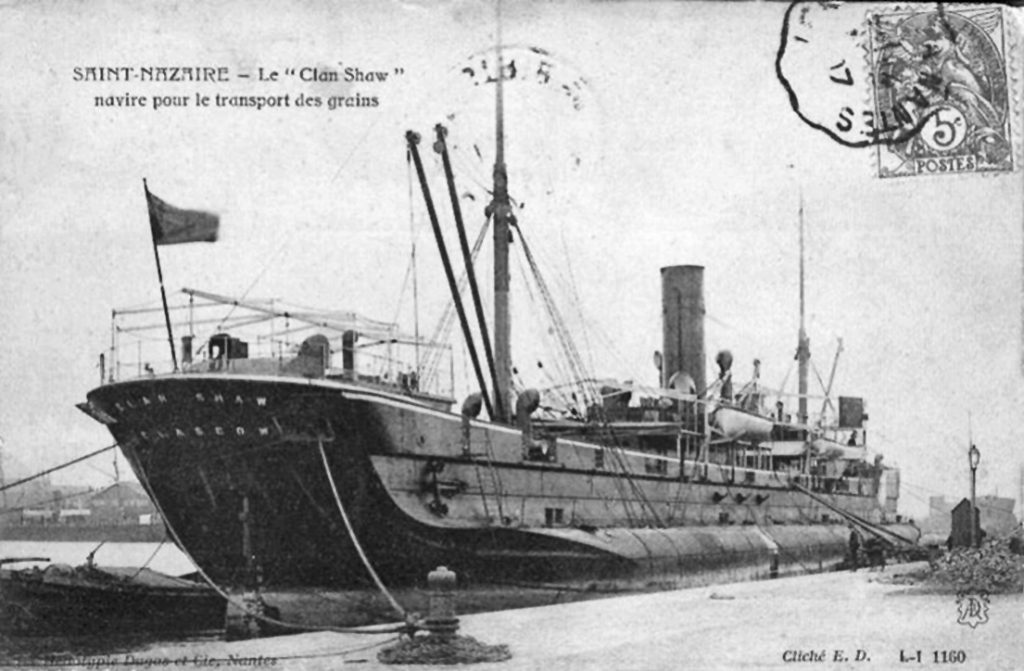

He is particularly fascinated, however, by the fate of the Clan Shaw – a jute liner mined by a German U-boat at the mouth of the Tay in 1917.

“Dundee lived with the consequences of that one for decades afterwards, “ he says, “with other ships striking the ill-marked wreck. There were huge damages claims against the Dundee Harbour Trust which almost bankrupted them. It was only through the intervention of the First Lord of the Admiralty, who happened to be then Dundee MP Winston Churchill, that the costs were reduced. But that didn’t stop Dundee kicking him out as MP a few years later!”

Steve Liscoe, Professional Assistant (Archaeology) with Fife Council said shipwrecks seem to be “topical and very popular” at the moment.

He has had a professional involvement in hydrographic and archaeological survey of shipwrecks in UK waters since the late 1970s, latterly working as part of a professional diving unit providing consultancy services to the UK Government.

He was also on staff at the Scottish Institute of Maritime Studies at St Andrews University.

He said: “To put the importance of Fife wrecks into context they account for about 12% of the marine archaeological resource for the whole of Scotland.

“With Fife having coastlines bounding two large river firths, both of which were major routes for maritime trade, the potential for earlier undiscovered wrecks, right back through the medieval period to the Roman occupation, is very real and exciting.”