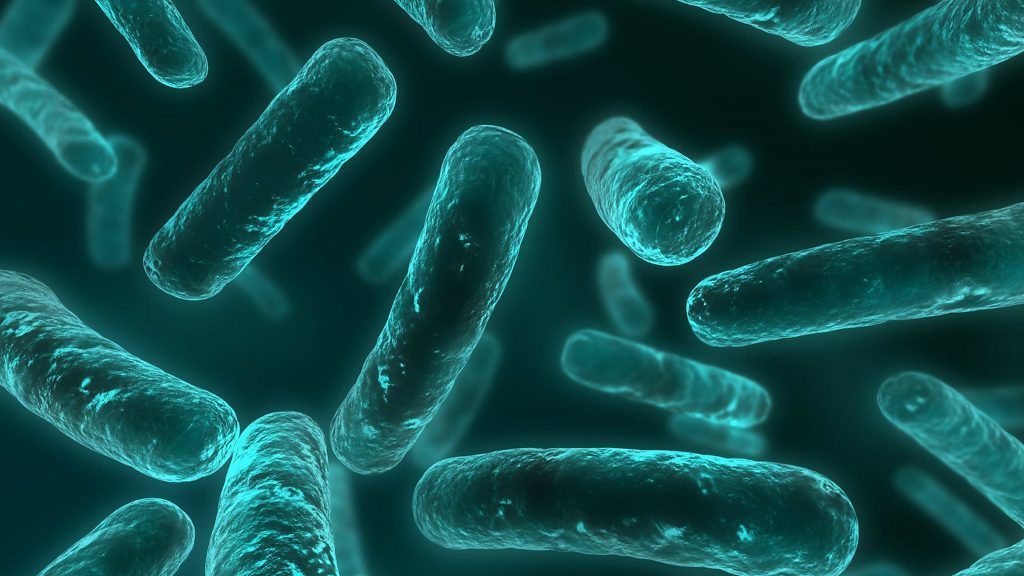

It has been described as an antibiotics apocalypse.

A world where a simple cut to your finger could leave you fighting for your life and where getting an appendix removed could prove deadly.

Childbirth could again become a dangerous moment in a woman’s life whilst cancer treatments and organ transplants could routinely kill you.

This might sound like the plot of a depressing science fiction novel, but it’s just three years since the World Health Organisation warned that the world is heading into a post-antibiotic era where these scenarios could be increasingly real.

Antimicrobial resistance to antibiotics will present a greater danger to humankind than cancer by the middle of the century, research warned, unless world leaders agree international action to tackle the threat.

Current estimates are that drug resistant infections already claim about 700,000 live per year globally.

And if we do not create new antibiotics, or prevent the loss of the ones we have, it is estimated that this will rise to more than 10 million deaths a year globally by 2050 with an additional global economic cost of £70 billion.

Ninewells Hospital-based Professor Dilip Nathwani – consultant in infectious diseases and honorary professor of infection at Dundee University – admits the figures are frightening.

A return to the era before Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin is potentially real – and already surgeons are “thinking more than twice” about hip replacement surgery for elderly patients prone to deep tissue infection.

But as he warns that the development has the potential to “unravel” all of the achievements by the NHS over the past 70 years, he is also optimistic about what can, and is, being done – with Dundee scientists at the forefront of world research to find a solution.

“I think that the public probably take for granted how antibiotics have transformed care in 50-60 years of modern health care,” said Professor Nathwani, who is chairman of the Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group and chair of the European Study Group on Antibiotic Policies.

“You don’t think twice now – you get a chest infection, a bacterial ear infection, you go for cancer surgery, your granny falls on the floor like my mum did when she came here and broke her hip –you get antibiotics to prevent infection.

“Now we are in a situation across the globe where many antibiotics are no longer effective and we are in very difficult situations where we are picking up bugs that are so resistant to antibiotics that they are virtually becoming untreatable.

“Thankfully in Scotland and the UK they are so far few and far between. But I’ve been in intensive care units in India, South Africa and elsewhere where it’s already a reality.”

Professor Nathwani said his “big topic” is “antibiotics stewardship” – trying to stop antibiotics’ use and for them to be used more prudently. He has produced a free e-book for clinicians which has been downloaded globally.

However, he also highlights the important work being carried out at Dundee’s Drug Discovery Unit to develop new antibiotics – which will also have to be used prudently and in turn will revolutionise the approach to health care. Important research is also being carried out by St Andrews University scientists.

He warned that antibiotic resistance has the potential to cause more deaths than diabetes and cancer put together within 30 years with a potentially devastating impact for the NHS.

But he is confident new drugs will continue to be developed by scientists. He added: “What we do need to do, however, is preserve what we’ve got for as long as we can.”

Professor Nathwani said another reason why new antibiotics have been slow to develop is because multi-national pharmaceutical companies did not generally see them as profitable.

A course of antibiotics taken over two weeks to fight an infection, for example, did not have the “net product value” or shareholders’ investment return of drugs taken by patients over the long term for “lifestyle” diseases such as obesity, diabetes or heart care.

It costs between £1 billion and £1.5 billion to bring a new antibiotic to market, and investors had to be sure of a return.

However, he said that discussions were taking place to make these companies realise that antibiotic investment was essential to humanity – as well as being essential to their own finances.

“We are convincing pharma that actually investing in these is essential for the greater good – and for their profits – because if they don’t their ability to treat cancer or to treat the fat person who gets an infection won’t be possible because there’s a good chance their customers will be dead,” the professor added.