Michael Alexander digs deep to explore the folklore behind some of Fife and Tayside’s most famous caves.

Swirling haar obliterates the rocky shore as the sound of crashing waves betrays the presence of the sea a few metres beyond.

Screeching seagulls wheel through the sky as the faintest scent of warm yellow gorse blends with a hint of sea spray in the warm breeze.

Despite the absence of the normally spectacular views across the Forth on this early summer’s day, the seasonal ‘pea-souper’ is suitably atmospheric for the trickle of rucksack carrying walkers negotiating this section of the Fife Coastal Path.

But for volunteers from the Save Wemyss Ancient Caves Society (SWACS), picking their way along the base of the ancient red sandstone cliffs between East Wemyss and Buckhaven, the weather conditions are ultimately irrelevant as we prepare to head underground for a tour of the ancient Wemyss Caves.

It’s 8000 years since the former sea caves – now raised up and set back from the shore as a result of isostatic sea-level change – were created by wave action following the end of the last Ice Age.

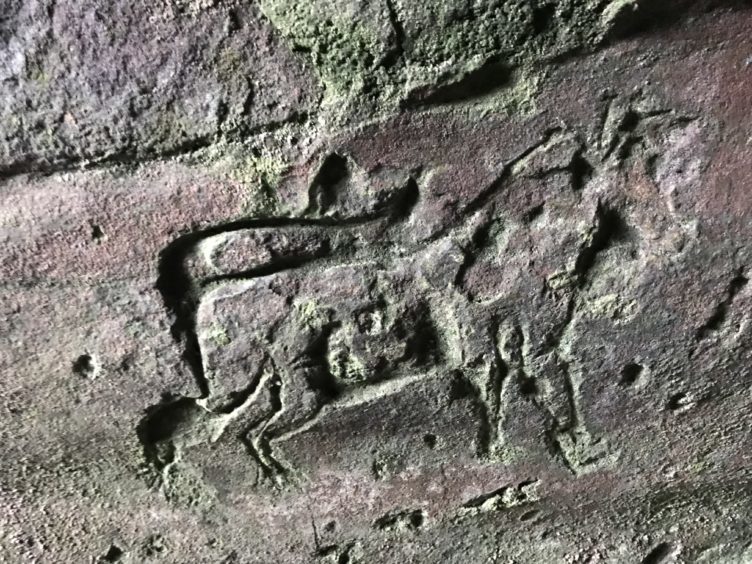

However, what makes them a nationally important heritage site is that they contain the largest unique collection of symbols carved 1500 years ago by people known as the Picts.

The caves along with the remains of Macduff’s Castle on the clifftop above are designated as a scheduled monument, and there is archaeological evidence of activity on and around the site for at least 4000 years.

However, despite being protected by law and despite ongoing efforts to safeguard their future, the caves remain under threat from coastal erosion and vandalism.

Escorting The Courier into the gloom of the Court Cave – so-called because local tradition says it was used as a court in the Middle Ages by the laird who lived in Macduff’s Castle – SWACS chair Mike Arrowsmith, 54, who works by day as a St Andrews University computer officer, explains that the society aims to secure the caves, carvings and other archaeological remains with ambitions to develop proper visitor centre facilities if the funding can be secured.

It follows the 4D Wemyss Caves Project which used the latest laser scanning and drone technology to record the coastline and caves in fine detail as they are now – and to allow visitors to digitally ‘step back in time’ to see the caves as they would have appeared to the Picts.

It’s difficult to see anything at first in the blackness.

But when Mike shines his flashlight onto one of the damp back walls – beyond a 1930s-built brick pillar helping to support the roof – he reveals 10 recorded Pictish carvings including mysterious midget cup marks in the shape of a cross which, while undoubtedly ancient, do not conform to typical Pictish symbolism.

From there we explore nearby Jonathan’s Cave. Nineteen early Christian crosses hidden at the rear suggest early Christian influence alongside carvings of five birds and a notable carving which, if Pictish, is the earliest depiction of a boat in Scotland.

Meanwhile, the Doo Cave was used as a doocot in the Middle Ages and still has pigeon boxes carved into the cave walls.

It was once linked to the West Doo Cave which contained 17 recorded Pictish carvings before collapsing under the weight of a heavy gun emplacement that was test fired in 1914.

Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs says the Kingdom has a “fantastic cave heritage” along its 186km of predominantly soft, sandstone coastline.

However, he says “no adequate explanation has yet been found to account for the wealth of Pictish carvings at the famous East Wemyss Cave complex.”

“What we can say,” he said, “is that Wemyss Caves, and indeed all of Fife’s caves, are archaeological treasure troves, literally time capsules waiting to be explored.”

Folklore is certainly at the heart of many stories surrounding Fife’s caves.

Constantine’s Cave at Fife Ness, for example, is reputedly the place where King Constantine was reputedly killed during a battle with the Danes in the 870s, although there is no direct evidence for his demise happening here.

Further along the coast towards St Andrews, Smugglers Cave – obscured half way up a cliff on the Kinkell Braes and only accessible by scrambling up a steep muddy track – conjures up images of a mysterious, potentially illicit past.

One of several caves below the Scores in St Andrews is fabled to be the final resting place of ‘The Smothered Piper of the West Cliffs.’ The legend, perpetuated by early 20th century writer WT Linskill, tells how a piper went into one of the caves for a dare and never returned.

Legend also has it that 8th century Greek monk St Regulus (later known as St Rule) took shelter in a long since collapsed cave between today’s St Andrews castle and harbour after being shipwrecked whilst transporting the relics of Saint Andrew “to the ends of the earth”.

After being taken in by the local Picts, the precursor for St Andrews Cathedral was built as a shrine to house the relics of Scotland’s future patron saint as a result.

“Many caves were used as important Christian retreats during the medieval period,” said Mr Speirs who contrasted the former Glass Cave at West Wemyss – Scotland’s biggest centre of 17th century glass production – to medieval devotional caves like St Margaret’s Cave in Dunfermline – the private devotional retreat of pious Queen Margaret, Scotland’s only canonised saint.

“Dysart, for example, takes its name from the Latin desertum which was borrowed into Old Irish by the 7th century and coined into place-names in Gaelic speaking Scotland (Alba) from the 8th to 12th centuries.

“The name means a place of solitude ie a religious retreat or hermitage and at Dysart we can be sure this site was St Serf’s Cave, still to be found in the grounds of Dysart’s modern Carmelite retirement home.”

Mr Speirs said pilgrimage sites like St Fillan’s Cave, below Pittenweem Priory, were important as was St Monans’ Cave, which was dedicated to the 6th century Irish saint, Moenu of Clonfert.

This cave was even known to have attracted kings with David II endowing the church there in the 1360s after his prayers were answered on a visit to the cave shrine and an old arrow wound, sustained at the Battle of Neville’s Cross in 1346, was miraculously cured – the arrow barb that had long troubled him, apparently popped out and his headaches ceased.

Andrew Wyntoun, the great 15th century Scottish historian, even compared Fife’s Caiplie Caves to the incredible troglodytic landscape and cave shrines of Cappodocia in Annatolia (Turkey), Mr Speirs added.

Caves, rock shelters and rock arches have also captured the imagination on the Angus coastline from Arbroath to the north end of Lunan Bay.

For example, Smugglers Cave at Carlingheugh Bay (commonly known in Arbroath as The Flairs) is located to the north east of Arbroath at the northern end of the Seaton Cliffs Nature Trail.

More mysteriously, national headlines were made 10 years ago when lifeboat crews discovered a mysterious house built into a cliff face near Arbroath while searching a stretch of coastline.

The home within a cave, a possible drinking den only accessible at low tide, was complete with wooden floor, seats, painted walls and tea tree lights.

Meanwhile, in Highland Perthshire, MacGregor’s Cave, near Kinloch Rannoch, was reputedly once a hideout for members of the outlawed clan.

In Victorian times the cave was ‘improved’ to become a picturesque spot for a walk and picnic.

In 2013, there was excitement when two Perth men rediscovered historic local cave the Dragon’s Hole hundreds of feet up the steeply wooded slopes of Kinnoull Hill.

Had they ventured there centuries ago, however, they risked a heavy fine – and incurring the wrath of the church.

In mediaeval times in May, according to records at the AK Bell Reference Library, local people celebrated pagan festivals at the cave and supposedly indulged in superstitious games, debauchery and “filthiness”.

But of course one of the most well-known Perthshire caves isn’t really a cave at all.

Ossian’s Cave at The Hermitage, near Dunkeld, was artificially constructed in 1785 after the poet James Macpherson published a series of ‘discovered’ ancient poems said to have been originally written in Gaelic by Ossian, son of Fingal.

The Hermitage was quickly ‘re-branded’ to exploit the mythology of Ossian – and the area continues being a popular tourist attraction to this day.