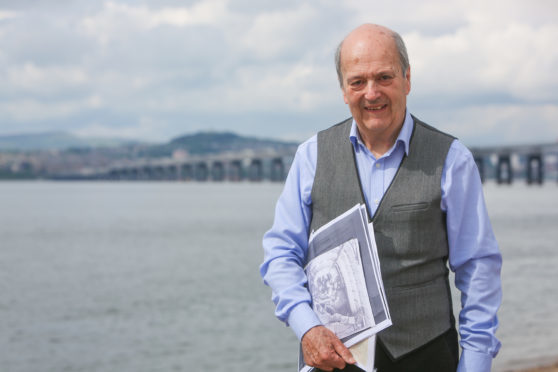

A former journalist has thanked Courier readers for helping him solve the mystery of a wartime parachute tragedy “cover up” that happened on the River Tay 75 years ago.

Michael Mulford, 71, a Dundee-raised former Courier and STV reporter who finished his career as RAF Public Relations Officer for Scotland, said an appeal through this newspaper’s Craigie column had helped him trace information about the drowning of seven fully-laden paratroopers who were dropped to their deaths during an exercise over Wormit Bay.

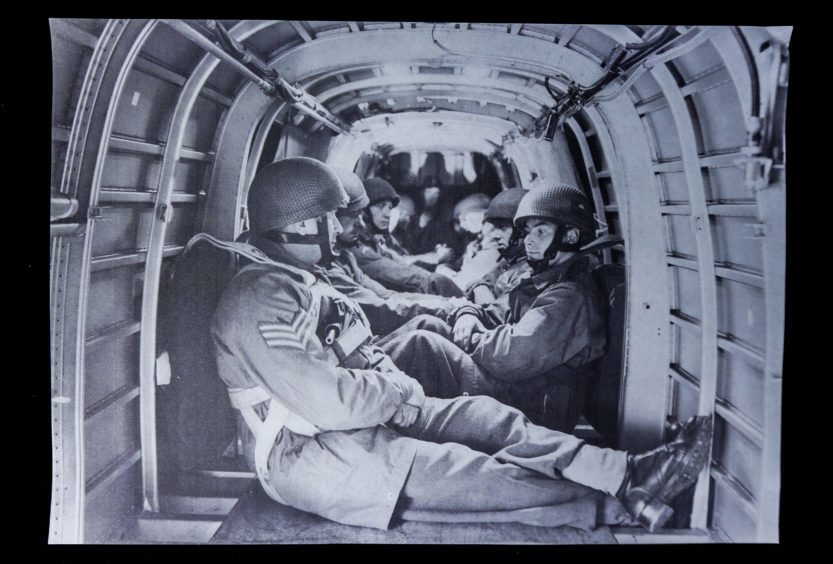

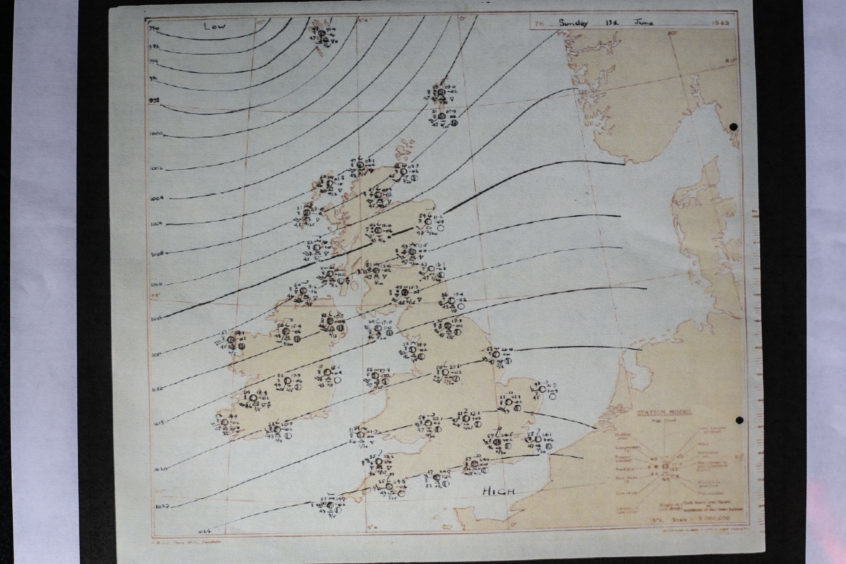

The men, training for the D-Day landings a year later, were supposed to be dropped 10 miles to the east at Tentsmuir as part of a top-secret exercise to see if paratroopers could be dropped into a tight space.

However, for reasons unknown, two of the 10 converted Whitley bombers that had flown from Salisbury Plain carrying 130 troops, veered around the coast towards Wormit and offloaded their men from an altitude of 800 feet into around 30 feet of water west of the Tay Rail Bridge.

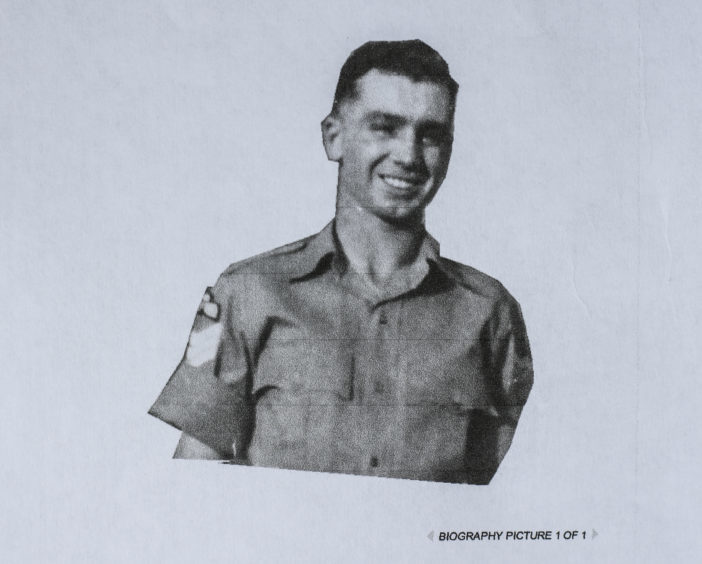

The second aircraft over Wormit contained nine men from the 8th (Midlands) Battalion of the Parachute Regiment.

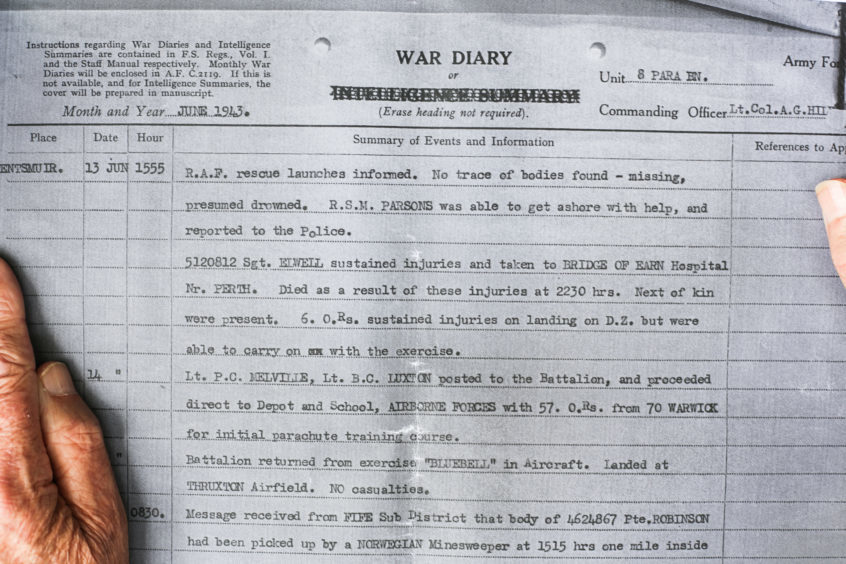

Seven drowned, one refused to jump after seeing his colleagues’ fate and was court-martialled.

The ninth, Regimental Sergeant Major Alan Parsons, landed on a narrow sandbank and made it ashore.

Another paratrooper died at Tentsmuir when he was struck during the jump by an ammunition box. Many others were injured.

Michael’s interest in the events of June 13, 1943, was sparked by his late mother Anna Mulford telling him over the years how she disbelievingly witnessed the whole episode as she stood on the beach at Wormit Bay while heavily pregnant.

Michael, of Cupar, said: “As a Royal Navy wife my mother knew that for many of the soldiers, if not indeed all of them, their last moments in this world would be the dreadful realisation that their circular parachutes had no control and that the only way from 800 feet was down to a watery grave.”

The rescue operation involved RAF Air-Sea rescue launches and the RNLI lifeboat from Broughty Ferry across the river east of Dundee.

A Polish officer who arrived told Michael’s mum “They are all ok.” However, she knew it could not be true. In fact, he was reporting correctly that 10 Polish troops had landed in the shallows and made it ashore.

When Michael started training as a reporter on The Courier in the mid-1960s, his mum implored him to ask the senior reporters who were on the paper in 1943 what had really happened.

However, they said they had never heard of anything of the sort.

Mr Mulford tried many times over the years to find out more about what happened but got nowhere.

Even as his mother neared her passing in 1994, aged 92, she was still asking.

However, six years ago, with the help of an appeal in The Courier, he traced Mr James Lindsay from Angus who had been a young boy in his family holiday cottage at Balmerino overlooking the scene.

He remembered not just the gold strands on his bedroom being illuminated by searchlights but also walking the beach the next morning and finding parachutes, helmets and kit strewn along the shore. Then an elderly ex RAF man got in touch saying he had been one of the airmen on the rescue launches.

Mr Lindsay recalled the authorities coming round insisting on a complete news clampdown.

It also emerged that the exercise had been taking place under the gaze of Lord Alanbrooke, the Chief of the General Staff of the Army and many of his top brass colleagues, who were assessing whether an airborne element to D-Day would work.

Michael added: “Digging deeper I established that the RNLI records had been heavily censored and that the log-books of the RAF launches held at the National Archives at Kew contained no references.

“What, then was the need for such total secrecy? The answer is this was a top-secret proving trial to see whether paratroops could be landed in a tight space. Their DZ (drop zone) that day was Tentsmuir on the west side of St Andrews Bay.

“The cover-up was deemed vital to prevent the Nazis getting any intelligence on which they could try to work out any details of D-Day.

“The details of the tragedy are briefly mentioned in the War Diary of the 8th Battalion, a document kept secret for decades after the war.

“My mum understood the need for secrecy.

“I doubt if she would have accepted the brutal sacrifice of lives to prove a point.

“She will be watching from a better place but will not have forgotten witnessing the tragedy on the Tay.”