As Halloween approaches, Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs talks about local efforts made to ward off ‘evil spirits’ in centuries gone by…

Have you ever found an old glove, a shoe or perhaps some broken pottery or rubbish under a floorboard?

Or perhaps you’ve noticed scratch marks on timbers when renovating an old house? Or what about small burn marks on rafters and beams, or even the occasional dried up old rat, bird or cat in a wall?

Such finds are common enough in older houses and at face value, they look like they must represent ordinary enough events – perhaps rubbish brushed out of sight by workmen and animals that have curled up in a quiet spot to die.

But according to Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs, these remains very often represent something much more sinister – something which, as Halloween approaches, may well capture the spirit of the season.

“What’s becoming increasingly apparent as more and more old buildings are studied is that these phenomena are not accidental,” said Mr Speirs.

“They’re actually part of a pattern and what they really represent are past measures to guard against evil.

“Indeed, it’s now clear, that from the 16th to the 19th century, the fear of evil spirits and the harm they could do was such a worry in Scotland that many, particularly in coastal communities, felt driven to take special measures; measures that employed magic to protect the home from evil.”

Mr Speirs explained that evil was considered to be everywhere in 16th and 17th century Scotland.

In fact, the problem was so bad that even King James VI felt moved to warn his subjects of the problem, penning his very own guide on the subject in 1597.

Daemonologie, as the work was known, is an evidence-based argument for the existence of evil and the widespread presence of witches.

The point was made clear in the opening sentence of the book, which read: ‘The fearefull aboundinge at this time in this countrie, of these detestable slaves of the Devil, the Witches or enchanters, hath moved me (beloved reader) to dispatch in post, this following treatise of mine to resolve the doubting both that such assaults of Satan are most certainly practised, and that the instrument thereof [witches] merits most severely to be punished.’

The Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 had of course made the use of witchcraft, sorcery and necromancy a capital offence. But now Daemonolgie served to remind doubters, that not only were witches ‘real’, but that they were everywhere and no one was safe!

So what to do about the problem?

“Of course the Scottish Church never condoned the practice,” said Mr Speirs, “but at the local level, the solution was to fight fire with fire, using sympathetic magic in the form of symbols to ward off evil.”

Known as apotropaic marks – from the Greek apotropaios, to ward off [evil] – Mr Speirs explained that the most common type of apotropaic symbol found in older houses in Fife are taper burns.

Appearing as tear-shaped scorch marks burned into timbers using a candle or taper (a fat-coated wick), the intention was to ‘innoculate’ the house against malignant fires by scorching taper burns (pseudo-fire marks) into weak points around the home, particularly around door jambs, window margins and mantle pieces.

“The reason,” said Mr Speirs, “is because these were the unguarded weak points in a house through which air-borne evil spirits could gain access to the home to set their malignant fires.

“Other common apotropaic symbols include mesh patterns and circular compass designs scratched on to timber or stone, intended to trap and pin evil spirits to the building in much the way as sticky paper traps and pins unwanted house flies.

“Again, these are mainly found at the ‘weak’ points in a building – around the doors, windows fireplaces and in the roof space.”

But Mr Speirs said of greatest interest are apotropaic deposits or ‘spiritual middens’.

These are caches of personal objects hidden in voids, usually in walls or fireplaces but sometimes under floorboards and in attic spaces – gloves, broken pottery, clothes, glass, clay pipes, bones area commonly found in such caches.

“Unlike the symbols that tended to ward off or trap evil spirits, the caches were intended to trick malevolent airborne spirits, the belief being that as if following a false scent, the spirits would latch on to the spiritual midden and not the living occupants of the house,” said the archaeologist.

“The archaeological interest of such deposits lies in our ability to date the objects, and what’s becoming increasingly clear is just how surprisingly late some of these deposits are”.

Mr Speirs said a 17th century house in Shore Street, Anstruther, for example, has yielded middens, symbols and taper burns.

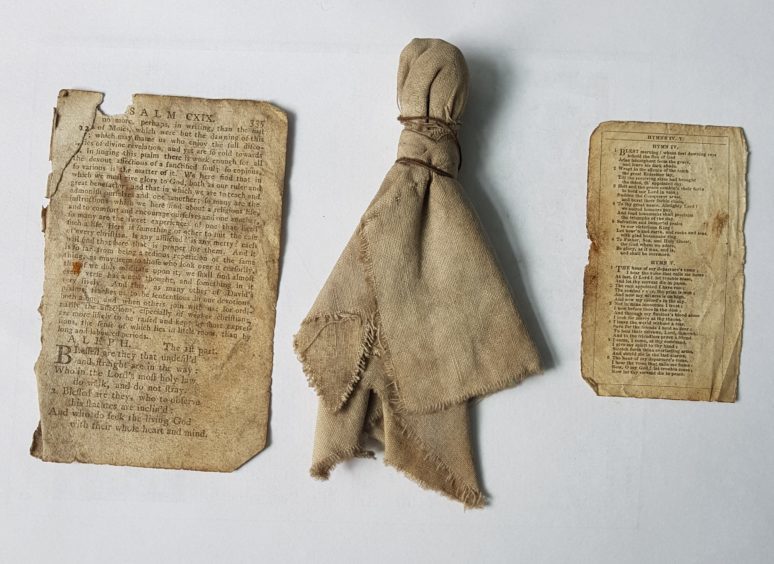

The earliest symbols and taper burns are 17th century in date but a spiritual midden found behind a lathe-and-plaster wall included pottery, a cloth doll, pages from a Bible, a George II half-penny, some ears of corn, dried peas and animal bones.

“Incredibly, it’s possible that this deposit was made as late as the 19th century,” added Mr Speirs.

Other local apotropaic finds include a table leg hidden in the wall of St Mary’s College, St Andrews and an early 17th century pointed shoe deliberately concealed below floorboards in a house on South Street, St Andrews.

Although he specialises in Fife, apotropaic markings and offerings would have been made Scotland-wide.

Mr Speirs, 48, who has been the Fife County archaeologist for 18 years, also now advises Dundee too.

He studied archaeology and medieval history at Glasgow and St Andrews universities.

He started off in commercial archaeology, worked a lot in England and abroad before becoming the Assistant Keeper (Research) Archaeology at Aberdeen in 1996.

He came to Fife in 2000 where he has been ever since, primarily advising on development and archaeology although he’s involved in every aspect of managing change in the historic environment. His specialist area is medieval archaeology – particularly the archaeology of medieval towns.

Asked why he became involved in archaeology, he laughed: “I can’t remember if it was the low wages or the poor career prospects that first attracted me but it’s good to know that by the Government’s new financial measure of skills, I’m barely out of the low-skilled category!”

But he is involved more generally in every aspect of the archaeology and medieval history of Fife.

At this time of year, and with the “witching season” approaching, it’s his favourite Halloween tales that Mr Speirs is often asked about.

One of the most poignant, he said, is the case of Lilias Adie – a poor woman accused of witchcraft who died in custody in Torryburn, West Fife, in 1704.

After she confessed to being a witch and having sex with the devil, she died in prison before she could be tried, sentenced and burned.

So the God-fearing locals buried her deep in the sticky, sopping wet mud of the foreshore – between the high tide and low tide mark – and they put a heavy flat stone over her.

“Her story would be lost amongst the hundreds of similar cases in 17th/18th century Scotland if it were not for the fact that she was buried in the inter-tidal zone under a big slab of sandstone,” said Mr Speirs.

“Why? To prevent Satan from re-animating her dead corpse. The minister was keen to prevent her from climbing out of her grave and terrorising him and the local community who condemned her to death.

“This is Scotland’s only known revenant (‘to return’) grave. Lilias’ story was made popular recently by (i) the discovery of her grave, and (ii) the facial reconstruction produced by BBC Scotland last year.

“This case perfectly illustrates the character of most Scottish witchcraft cases – petty village squabbles and the victimisation of the vulnerable being legitimised by a theologically misguided clergy only too willing to use violence to create their vision of a Godly society.”