In an exclusive interview marking the 30th anniversary of the Lockerbie bombing, Michael Alexander speaks to an American terrorism expert whose university is marking the loss of 35 of its students in the attack – and hears the ‘hellish’ memories of several journalists who covered the aftermath.

Cruising at a height of 31,000 feet and packed with students embarking on the long journey home to America for Christmas, passengers on board New York-bound Pan Am flight 103 were just 38 minutes into their flight from London Heathrow when at 7.03pm on December 21, 1988, a bomb exploded on board as the Boeing 747 flew over the Scottish borders.

As well as killing all 259 people on the aircraft, the falling debris which hit the town of Lockerbie two minutes later, also wiped out 11 people on the ground.

As bodies, luggage and debris tumbled six miles through the sky, the most devastating carnage in the town came as the wings containing thousands of gallons of aviation fuel exploded on impact – gouging out a huge crater in Sherwood Crescent and obliterating two houses and their inhabitants with it.

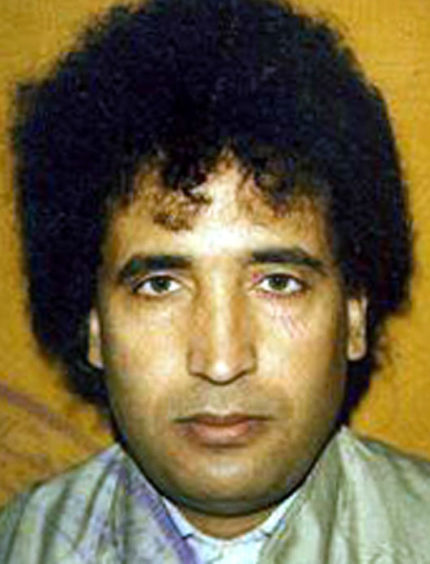

In 2001 Abdul Baset Ali al-Megrahi, a Libyan intelligence agent, was found guilty of the bombing.

After being diagnosed with prostate cancer, the Scottish Government released him on compassionate grounds on August 20, 2009 and he died on May 20, 2012, two years and nine months after his release.

However, 30 years after the atrocity – the worst civil aviation disaster in British history – there’s still a sense of justice having not been done.

As commemorations to mark the 30th anniversary take place in Lockerbie, special events are also being held at New York state’s Syracuse University.

Among the 179 Americans killed in the bombing were 35 of the university’s students who were returning home from a semester abroad in London and Florence, Italy.

It’s a chapter which is of particular interest to terrorism expert Dr Corri Zoli – Syracuse University’s director of research at the Institute for National Security and Counterterrorism, and a teaching professor of law.

In an exclusive interview with The Courier, she revealed she was recently briefed by the FBI and Scottish prosecutors on the ongoing criminal and civil cases against alleged co-conspirators.

While she knows there was controversy around al-Megrahi’s prosecution, she thinks there was “good strong evidence” for him being involved – particularly as the late Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi admitted his country’s involvement in 2003.

She’s confident that, despite the complications of a trans-national investigation and liaising with “unstable” countries like Libya, further prosecutions will take place.

“I had a briefing fairly recently from the FBI and the Scottish prosecutors on this,” she said.

“They talked about the various leads that they were pursuing in this long process.

“They actually were closer to finding information in part because there has been destabilisation in Libya.

“They were getting access to records they hadn’t been able to gain access to before. So I do think there will be that level of justice in terms of prosecuting people beyond those who have already been prosecuted.”

Dr Zoli, who has worked at Syracuse since 2009, said the bombing of Pan Am flight 103 was “shocking” in all the ways that terrorist attacks are shocking.

It was atypical in that hijackings were the most prevalent form of terrorism at the time and, some 13 years before 9/11, it was unusual in that it targeted Americans. It was also relatively rare for bombs to eliminate aircraft in flight.

However, the fact there were 35 American students on board from a single university was in itself “quite unprecedented”.

“I think the impact here (at Syracuse) has been we were on the direct frontline of a terrorist attack – again quite unusual for a university institution,” she said.

“I think it brought the community together. Folks were involved at every level. I know administrators called parents to reassure them.

“There were nearly 20,000 students at Syracuse University. I don’t think they called them all but they certainly called friends and roommates of the students who were on the flight.”

Dr Zoli said the legacy of Lockerbie at Syracuse included the establishment of 35 remembrance scholarships named after every student who died as well as two scholarships each year which give Lockerbie students the opportunity to study at Syracuse.

Commemorative events at Syracuse this week include tree planting on the south campus and a remembrance service coinciding with the exact moment of the tragedy.

This will coincide with a service at the Pan Am 103 memorial cairn at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington DC, organised by the Victims of Pan Am Flight 103 families group.

Syracuse is also hosting a special exhibition ‘We Remember Them: The Legacy of Pan Am Flight 103’.

However, while most Americans will remember Pam Am flight 103, Dr Zoli doesn’t know if the wider US public remember the details of the attack and the way it affected the US and Scotland. It certainly isn’t remembered in the way 9/11 has been since 2001.

“One of the most significant things to come from Lockerbie,” she said, “is that the families who came together on both sides of the Atlantic in the aftermath of the attack – The Victims of Pan Am Flight 103 families group – pushed for the transportation security and authority types of elements that we see today: Things we take for granted now like your luggage not being able to travel apart from you, and other elements such as enhanced luggage screening.

“These are very basic protective mechanisms. A no brainer in a way. Low hanging fruit. But this group really was responsible for initiating these policy changes.

“It’s quite unusual in that we’ve had other tragedies and attacks where the affected communities and families did not get together and become a policy force. In this case the group should be commended.”

Lockerbie is a strong community that will always remember the victims of the bombing with respect and sadness.

However, the town does not simply want to be defined by what happened that night 30 years ago.

That is the view of former ITN journalist, and regular Courier Weekend magazine columnist Fiona Armstrong who, as Lord Lieutenant of Dumfries, will be laying the first wreath at a remembrance service at Lockerbie cemetery on Friday December 21 and will be reading out a message on behalf of the Queen.

Fiona, who now lives near Lockerbie, has covered stories on the disaster on and off for the last 35 years for ITV Border.

On the night of December 21, 1988, she was sent up to the disaster scene from London as a reporter with ITN.

Not surprisingly after three decades, it’s a night she still remembers with “great clarity”.

“Arriving in the small market town it was what I imagine it must have been like after the blitz in Glasgow or London,” she told The Courier.

“The darkness, a smell of burning rubber and petrol, a pall of thick smoke over the town, small fires burning in the streets – and despite the work of the emergency services, strangely an eerie silence.”

Fiona explained that the people of Lockerbie had wanted a low-key event this year.

They had thought that the 25th anniversary would be the last ‘big’ memorial event.

However, it has emerged that because so many people want to come ranging from former Pan Am employees and American families to two busloads of military veterans from Glasgow who helped in the search for bodies in the days after the disaster, it is unlikely to be quiet after all.

Fiona acknowledges that before the bombing, Lockerbie was a small Scottish market town that probably few had heard of.

However, the name ‘Lockerbie’ has become synonymous as ‘the town the plane fell on’ – and she knows of local people who, for some years after, would say they were from ‘near Dumfries or Gretna’ if asked because saying Lockerbie caused an inevitable reaction.

Fiona added: “The plane could have fallen anywhere, but this terrible thing happened to Lockerbie – and Lockerbie folk showed what they were made of.

“Helping with searches, providing food, comforting victims’ families, offering friendship and accommodation to American relatives.

“Lockerbie women washed the clothes of those who died on the plane so they could be sent back to grieving relatives.

“But the town’s motto is ‘Forward Lockerbie’ and whilst never forgetting it now has to be able to move on.

“This is a strong community. It pulled together and whilst it will always remember the victims with respect and sadness, it does not simply want to be defined by what happened that night three decades ago.”

Meanwhile, a retired DC Thomson & Co Ltd journalist has recalled how reporting from Lockerbie on the night of the disaster was like gazing into the “bowels of hell”.

Campbell Gunn, a former political editor who went on to serve as special advisor to two Scottish First Ministers, was the newly-appointed chief reporter of the Sunday Post’s then Edinburgh office when news broke on December 21, 1988, and he rounded up two colleagues to attend the scene.

Campbell admits that they used “some subterfuge” to get near the town, as the motorway was closed and there were long tailbacks on the approach roads.

However, even from a few miles distant, the smell of burning fuel was heavy in the air, and in the distance they could see a glow in the sky.

“Police officers were obviously tied up in the town, and it was left to an AA man to direct traffic away from the motorway,” he said.

“I showed him my press card and lied to him that the police had told us to come this way. He waved us on to the motorway with a warning: “Drive south on the northbound carriageway. There shouldn’t be anything coming the other way, but put on full beam just in case.’

“The result was that a few minutes later we were standing gazing into what looked like the bowels of hell, on the edge of the huge crater at the side of the motorway where the fuel-laden wings had landed, exploded and were still burning.

“The rest of the night was spent speaking with witnesses, attending press conferences in the town and sending regular updates to head office from a telephone box – no mobiles in those days, remember – before heading home at seven in the morning.”

Campbell explained that in the years that followed, Lockerbie became a major part of his journalistic life.

He attended the press conference where the then-Lord Advocate announced the charges against Megrahi and his co-accused, Khalifa Fhimah.

He was at Camp Zeist in Holland when the two accused flew in for trial, and he was at Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill’s press conference when he announced he was to release Megrahi.

In between these events were a number of interesting asides. He knew the late MP Tam Dalyell, who campaigned long and vociferously that Megrahi was innocent.

On one occasion, after there were reports in the American media containing details of documents relevant to the inquiry which were available under US freedom of information, but which were unavailable in Scotland, he asked Tam if there was anyone he knew who could help.

He was put in touch with the ‘First Secretary at the US embassy’ – whose real job was head of the CIA in Europe – and, after a long face-to-face chat, had all the American documents forwarded to him by the US State Department.

Campbell has been reflecting on his own coverage this week.

However, most importantly he’s reflecting on the fact that not one of the main players in the attack, whether in Iran, Syria or Libya, has ever been brought to justice – nor at this distance in time are they ever likely to face a criminal court in Scotland.

That, he says, is a “tragedy for the Scottish, UK and American justice systems” – although he hopes justice will eventually prevail.