Michael Alexander speaks to Courier Country Germans and a St Andrews University academic about the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the lessons learned – on both sides.

It is one of the most famous moments in recent European history.

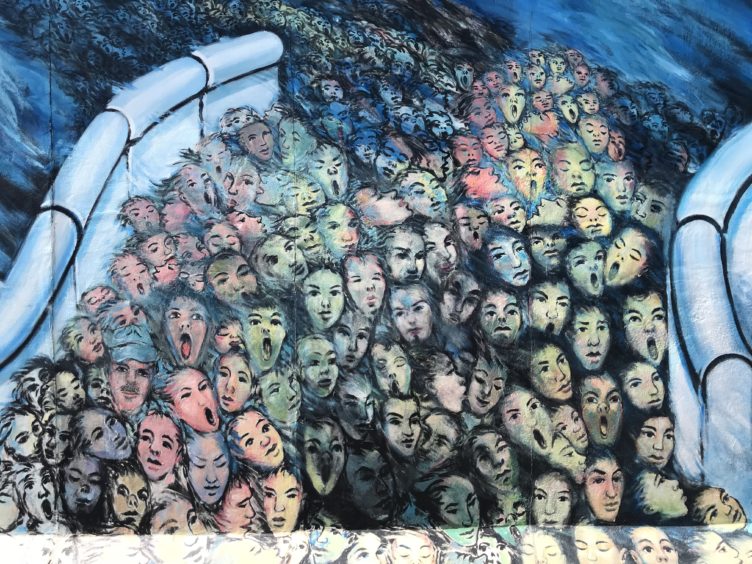

On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall which had kept East and West Berliners divided for almost 30 years, was breached by jubilant Berliners.

The fall of the almost 90-mile barrier, which was built by the East German regime in 1961 to prevent East Berliners fleeing to the West, came amid a wave of revolutions that left the Soviet-led communist bloc teetering on the brink of collapse and helped define a new world order.

But as the anniversary is commemorated with a special concert in front of the Brandenburg Gate on the evening of the 30th anniversary, Tom Smith, a German lecturer at St Andrews University said that despite modern Berlin coming to terms with its complicated layers of 20th century history, the legacy of its Cold War divisions live on.

“I think it’s the experience of the wall disappearing that interests me the most,” said Tom, 32, who first visited Berlin on holiday as a child and who now specialises in the experiences of minorities around 1989 and in the music scene that sprung up afterwards.

“It was such a huge shift in the lives of millions of people who suddenly found their entire identity different because quite literally the boundary that defined their lives disappeared. They suddenly had to negotiate what their life and their sense of self looked like in this new world and in this new system.

“That’s what’s so fascinating. It’s this rupture in peoples’ lives that doesn’t really have an equivalent anywhere else in the world.”

While many nightclubs and record labels opened up in the abandoned spaces left by the wall, Tom said assumptions are still often made about what it meant to be from the East or West. Political voting patterns often still reflect those past experiences and the socio-economic legacy.

However, what’s really struck Tom through his research is how different the experiences were for people of colour in Berlin when the wall came down.

“The history of the wall is often about people coming together and new opportunities and unity,” he said.

“But also what you get at this time is a really sharp increase in racially motivated violence.

“There’s this sudden moment with the wall coming down of people asking what it means to be German, this also leads to an increase in right-wing violence.

It was by no means a uniform story of people coming together.”

Perth-based chartered civil engineer Tanja Waaser, 46, who lives in Meigle, Perthshire, grew up in Meerbusch in the Lower Rhine region of West Germany.

As a child of communist parents and grandparents, she had a “different perspective” of the East and a “bit of a difficult relationship” with the West.

“West Germany’s attitude towards the left-wing intellectuals was critical and many were blacklisted and could not work in their professions,” she said.

“Kids in school tried to bully me for having communist parents, probably jealous of our yacht and their parents not being able to understand that communists can be well off.

“Not all was great in the West or the East, it was just different.”

During Baltic Sea holidays in the East, where there was “less bling and life was probably harder”, she remembers local surfers being disappointed that her dad’s ‘western’ surfboard was no different from the ‘eastern’ boards.

When the Berlin Wall came down while she was on a school trip to London, however, she remembers how it was a “great surprise, so unexpected and totally surreal” as she watched developments unfold on TV.

“What came afterwards was a big injustice and shame for everyone in the West and in the East,” she said.

“The East was just annexed by the West.

“Companies flooded into the East to buy cheap assets, get government grants and then close down factories, making loads of money, leaving people without a job and hope behind.

“In the West there was no need to keep standards high because the East was gone so no need to live up to expectations.

“To this day people in the East still get a lower salary and there is a higher unemployment rate. With the West taken over the East, Germany has never managed to grow together in all these years which is a shame as we are all one people.

“The unification could have healed all these years that separated Germany and I hope we have not missed our chance.”

Fife maths teacher Till Soltesz, 49, who lives in Cupar, was very aware of his country’s separation growing up in the university city of Freiburg in south-west Germany’s Black Forest.

The son of a former East German who moved to the West aged 12 before the border was closed, the ‘East’ was ‘other’ when he was growing up.

“They were part of the Warsaw Pact and on the other side of the Iron Curtain,” he said.

“We spied on them, they spied on us, we competed against them at the Olympic Games or at football. There wasn’t much connection. You didn’t cheer when the GDR bobsleigh won a medal.

“Yes, we felt sorry for the people living there, because they weren’t allowed lots of things and they couldn’t buy as much as we could. But East Germany was a different world. They had a bad government.”

Till explained, however, how all those feelings and views were “gone in a millisecond” the moment the wall opened on November 9, 1989.

“Suddenly we were one country, one people,” he said.

“The bad suppressing government was gone, the poor people were freed.

“Ok, it didn’t really come as a surprise. There was a big build up. There were all the Monday demonstrations, which grew bigger and bigger.

“It was clear they (the East German Government) couldn’t hold it together. Lots of people also fled before November 9 via Hungary.

“However, seeing happy people running through the borders and climbing over the wall, it was a great realisation.

“I like to believe that many Germans felt the same at this point – the big relief that an era of separation is over. And I do remember my parents being very excited and emotional.”

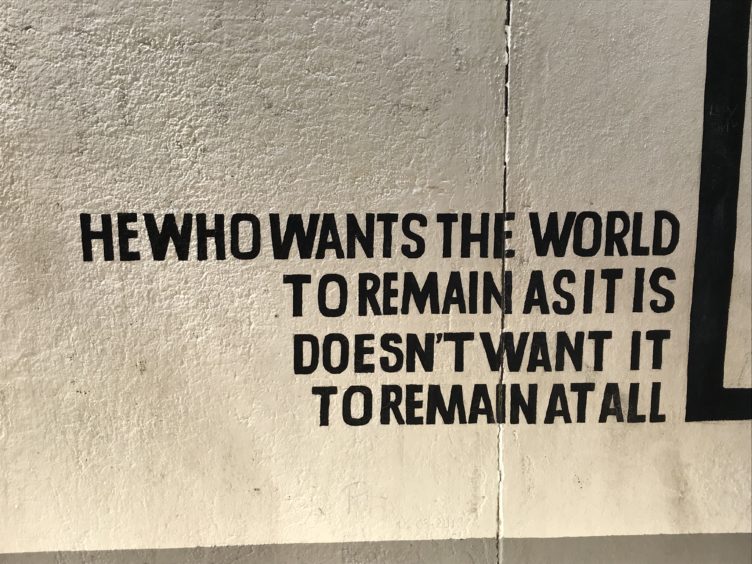

Till said the lessons from the Berlin Wall should be that “separation is something which creates bad feelings and makes it much more difficult to see things the way they are.”

However, the more he’s learned about the GDR, the more he’s realised that not everything was bad in Eastern Germany.

He added: “For me personally one other thing stands out. As a German, there are not many things I can be proud of when I look at our history, but I am proud of these protesters from the Monday Demonstrations, proud of the people of the GDR.

“They proved that a revolution – the downfall of a government – can be achieved in a peaceful way without any violence. I think that is something we can learn from.”