A spacecraft on a historic mission to Jupiter is circling the planet as scientists prepare for their closest look ever at the mysterious gas giant.

The Juno probe is executing two wide orbits, each lasting 50 days, as vital systems and instruments are checked.

At the end of the 100-day waiting period, a blast from its rocket engine will send the craft on a new trajectory, swooping low over Jupiter’s equator every two weeks.

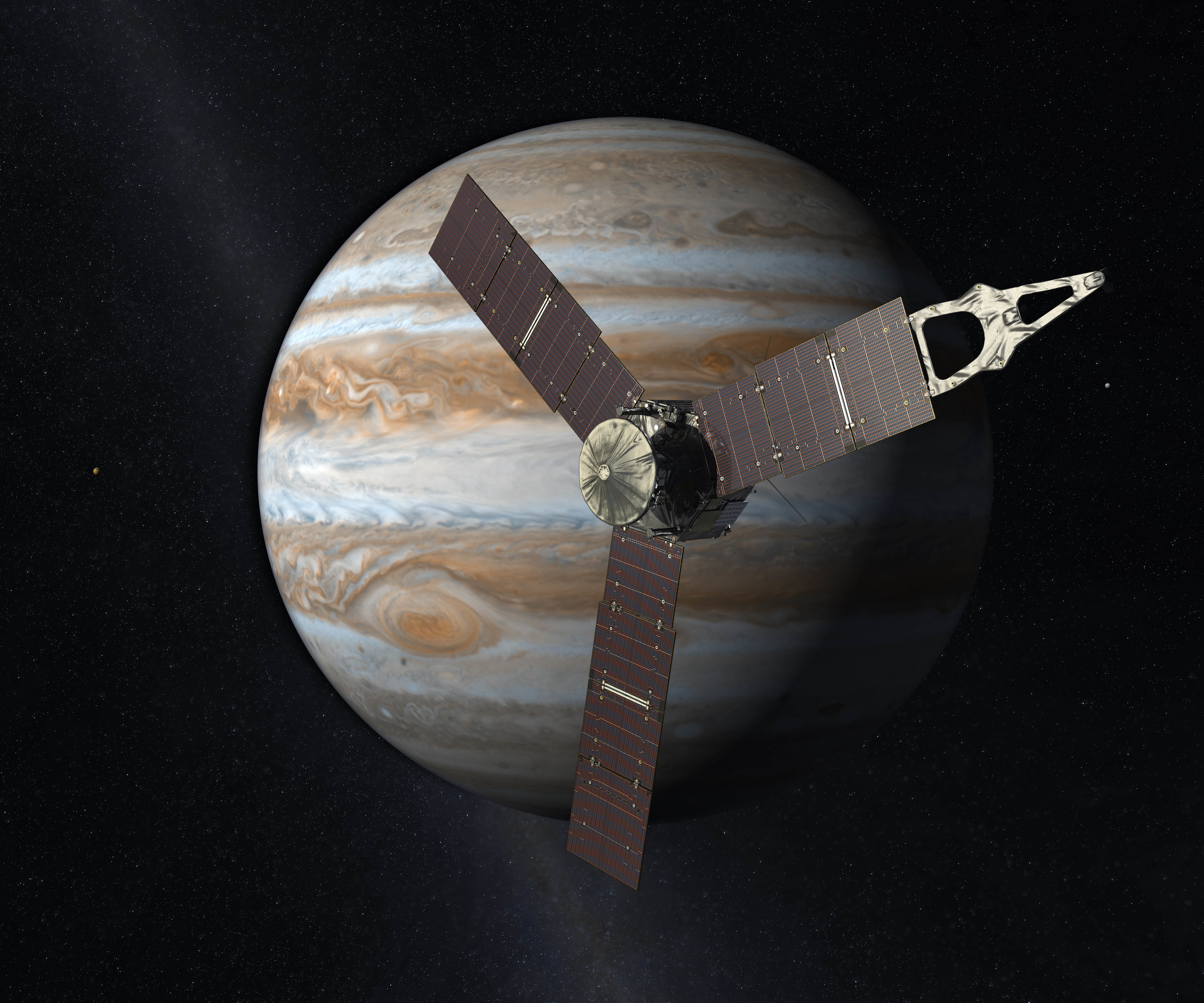

The spacecraft, powered by three huge solar panels, will fly to within 2,900 miles of Jupiter’s swirling cloud tops – closer than any man-made object has gone before.

It will send scientists on Earth a treasure trove of data about Jupiter’s composition, gravity, magnetic field and the source of its raging 384mph winds.

A panoramic camera will return colour photographs that promise to be breathtaking.

Travelling at 150,000mph, Juno reached Jupiter at 4.18am UK time on Tuesday after a five-year 1.8 billion-mile journey through space.

A 35-minute engine burn reduced the spacecraft’s speed by 1,212mph and sent it into orbit.

Cheers and applause erupted in mission control at the American space agency Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California when a signal confirming completion of the burn was received at around 4.54am.

A 10-strong team of scientists from the University of Leicester is playing a key role in the mission, which aims to find clues to Jupiter and the solar system’s formation.

The British researchers will analyse data on Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field, its spectacular auroras, and its dynamic atmosphere. They will combine information from Juno with that from ground-based telescopes on Earth.

Dr Leigh Fletcher, from the university’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, said: “What Juno is really trying to do is get down really deep, deeper than we’ve ever been able to look before.

“From the ground we can look at the high level stuff and combine it with the deeper data from Juno to produce a 3D picture of the atmosphere.”

A key part of the mission will measure Jupiter’s internal density from the way the planet’s gravity slightly disturbs Juno’s orbit.

“If we detect a core that will allow us to understand how the planet formed in the first place,” said Dr Fletcher.

“That really is at the heart of the Juno mission. Does Jupiter have some sort of solid rocky core or not? It could have formed with a core, from an embryo of rock and ice, or in a similar way to a star, without a core.”

Studying Jupiter is of great importance to astronomers because of the way its enormous gravity influences the “architecture of the solar system”, said Dr Fletcher.

He added: “It causes material to be flung about and we believe it migrated inwards and outwards during the early stages of the solar system’s formation.

“In other solar systems we’ve seen gas giants close to their stars, and maybe they’ve migrated in. If Jupiter had done that, we wouldn’t be having this conversation now.”

Juno has been strengthened to withstand the circuit-frying radiation around Jupiter. Its vital flight computer is housed in an armoured vault made of titanium and weighing almost 400lb.

At the end of its 20-month mission it will be sent on a one-way plunge into the planet’s thick atmosphere.

Dubbed the “biggest, baddest planet in the solar system” by the Juno team, Jupiter is surrounded by a field of high radiation streaked with particles energised by its immensely strong magnetic field.

It also has a ring of dust and rock similar to its neighbour, Saturn, posing a further threat to the probe.

The previous record for a close approach to Jupiter was set by Nasa’s Pioneer 11 spacecraft which passed by the planet at a distance of 27,000 miles in 1974.

Only one previous spacecraft, Galileo, which visited Jupiter and its moons from 1995 to 2003, has orbited the planet.

Juno was launched into space by an Atlas V rocket from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on August 5 2011.

The mission is part of Nasa’s New Frontiers programme of robotic space missions which last year saw the New Horizons craft obtain close-up views of dwarf planet Pluto.

Unusually for a robotic space mission, Juno is carrying passengers – three Lego figures depicting the 17th century Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, the Roman god Jupiter, and the deity’s wife, after whom the probe is named.

Lego made the figures out of aluminium rather than the usual plastic so they could withstand the extreme conditions of space flight.

A plaque dedicated to Galileo and provided by the Italian Space Agency is also on board.

Measuring 2.8in across, it shows a portrait of Galileo and a text written by the astronomer in January 1610 while observing Jupiter’s four largest moons – later to be known as the Galilean moons.