Tony Blair is facing the threat of legal action over his decision to take Britain to war in Iraq, after the long-awaited Chilcot Report delivered a damning verdict on his government’s justification, planning and conduct of military intervention in 2003.

Families of some of the 179 military personnel killed in Iraq branded the former prime minister a “terrorist”, while Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn said the report made clear that the invasion was “an act of military aggression based on a false pretext”.

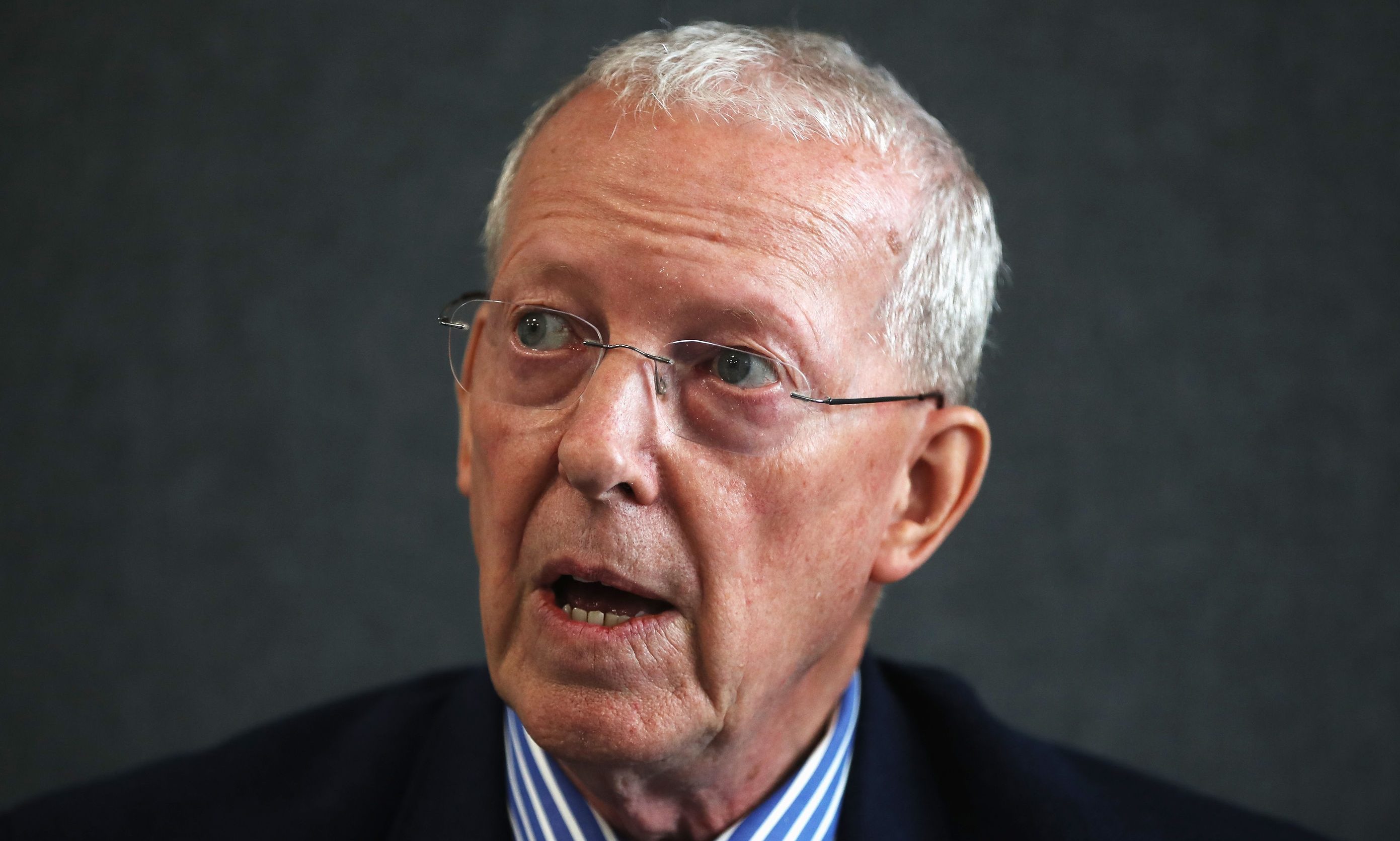

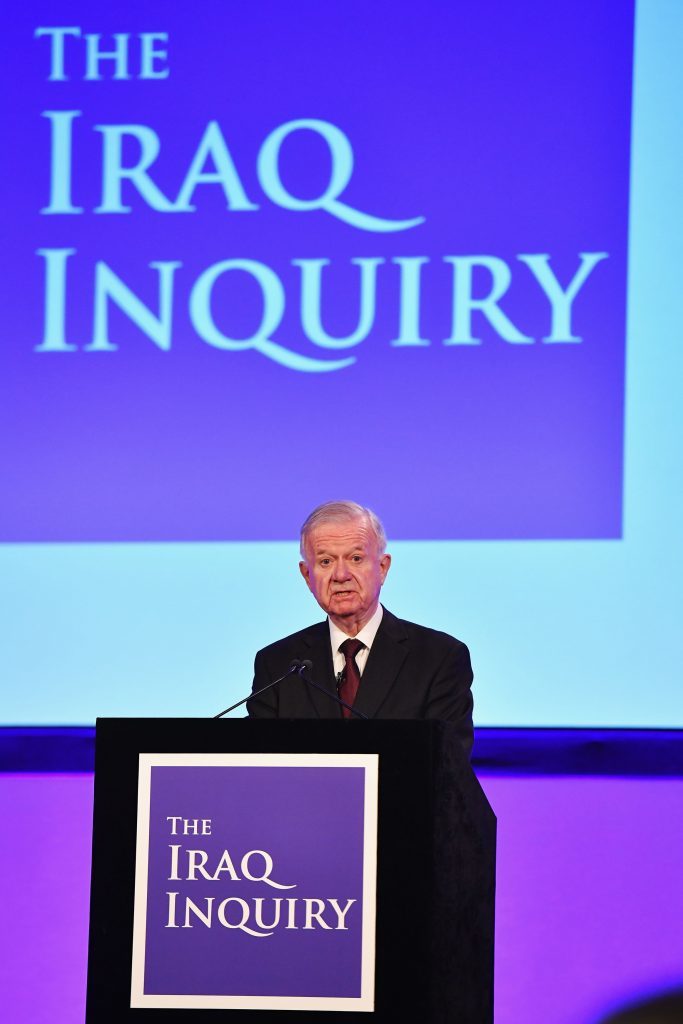

Unveiling his report into the UK’s most controversial military engagement since the end of the Second World War, Iraq Inquiry chairman Sir John Chilcot said the war “went badly wrong, with consequences to this day”.

He made no judgment on whether military action was legal, but found that then attorney general Lord Goldsmith’s decision that there was a legal basis for UK involvement in the US-led invasion was taken in a way which was “far from satisfactory”.

Key findings in the long-delayed report included:

»»The case for war was presented with “a certainty which was not justified”

»»It was based on “flawed” intelligence about the country’s supposed weapons of mass destruction (WMD) which was not challenged as it should have been

»»The use of force to remove dictator Saddam Hussein was undertaken at a time when he posed “no imminent threat” and in a way which undermined the authority of the United Nations Security Council

»»Planning for post-conflict Iraq was “wholly inadequate”, with shortfalls in armoured vehicles to protect UK troops which “should not have been tolerated”

The report did not support claims that Mr Blair agreed a deal “signed in blood” to topple Saddam at a key meeting with George Bush at his ranch in Crawford, Texas, in 2002.

But it revealed that in July that year – eight months before Parliament approved military action – the PM committed himself in writing to backing the US president over Iraq, telling him: “I will be with you whatever.”

Mr Blair acknowledged that the report contained “serious criticisms” and said he took “full responsibility for any mistakes, without exception or excuse”.

But he said he still believed it was better to remove Saddam and insisted that the inquiry’s findings should “lay to rest allegations of bad faith, lies or deceit”.

His decision to send troops into action was taken “in good faith and in what I believed to be the best interests of the country”, he said.

Tearful families of some of the 179 UK military personnel who died in Iraq responded with fury to the details of shortcomings in planning and preparation uncovered by the seven-year inquiry.

Reg Keys, who was among relatives who came to London to have an early sight of the 2.6 million-word report, said it was clear that the prime minister “deliberately misled” the country over the threat from Saddam and that his military policeman son Tom “died in vain”.

Sarah O’Connor, whose brother Bob died when a military plane was shot down near Baghdad in 2005, branded Mr Blair a “terrorist”, while Roger Bacon, whose son Matthew was killed by a roadside bomb, said the families reserved the right “to call specific parties to answer for their actions in the courts”.

The families could not be “proud” of the way the government treated their loved ones, Mr Bacon said, adding: “Never again must so many mistakes be allowed to sacrifice British lives and lead to the destruction of a country for no positive end.”

Announcing a two-day parliamentary debate on the report next week, Prime Minister David Cameron – who voted for war in 2003 – told MPs: “The decision to go to war came to decision in this House. Members on all sides who voted for military action will have to take our fair share of the responsibility.

“We cannot turn the clock back but we can ensure that lessons are learned and acted on.”

The PM cautioned that the experience of Iraq should not prevent Britain from collaborating with its close ally the USA in future military action.

In a scathing assessment of Mr Blair’s actions over Iraq, Mr Corbyn – who opposed war from the start – said the invasion had been judged illegal by international authorities. But he stopped short of calling for his predecessor as Labour leader to be tried for war crimes, as some had expected.