As famine in Africa leads aid agencies to warn of potential starvation for 20 million people, three Courier Country humanitarian aid workers, with different experiences in Greece, Turkey and Sarajevo, tell Michael Alexander about life on the front lines.

The millions of refugees fleeing war, violence and persecution across Africa and the Middle East might not be making the headlines they did during 2015 and 2016 – and the numbers arriving are down considerably after Europe’s borders were effectively closed to new entrants last year.

But that doesn’t mean migrants are no longer taking their chances aboard unseaworthy boats and dinghies in a desperate bid to reach the continent.

By late March, more than 24,000 refugees had arrived by sea in Greece and Italy already this year – a vast reduction on the 362,376 in 2016 and 1.3 million the year before, but the fate which awaits them is every bit as wretched.

An estimated 62,000 of those who have chosen to make the perilous sea crossing from Turkey to Greek islands like Kos and Leros now find themselves stuck in “holding pens” after a treaty signed last year blocked their onward passage into the EU and Turkey closed its border behind them.

Fife man Chris Mitchell, 64, has gained first-hand experience of the plight facing many refugees after volunteering for the second year running with local relief organisations.

The grandfather-of-two, from Kinghorn, spent four weeks last spring on Kos after being moved by images he saw on TV.

The former Fife Council officer had been made redundant in 2011 but with 25 years’ experience as an RNLI and Coastguard volunteer in Kinghorn he felt well placed to help those in need and returned to Leros for three weeks in February and March.

He has been volunteering with Aegean Solidarity Network (ASN) Team UK but his support has also taken a more unusual turn in the form of music lessons.

Inspired by the Fife Ukulele Orchestra programme, which teaches the instrument to youngsters back home, he took 15 ukuleles and tuition packs to Leros so adults and children from the camps could spend time on an activity that took their minds off the squalor around them.

“Local people in groups like Leros Solidarity have made a huge humanitarian effort for many years,” says Chris.

“They provide food, shelter, and clothing to unaccompanied children, families and adults from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan and other war torn countries.

“They have relied on donations and volunteers along with collaboration with the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), larger NGOs like Save the Children and the Greek government.

“Through their efforts the basics to maintain life are largely met on Leros. But a stalled life in a camp, going nowhere is soul-less and damaging to mental health.”

And that’s where the ukulele comes in.

“The focus now is to provide education for the children, and language, training and other activities for all, as well as helping them integrate into the local community,” says Chris.

“Who knows how long they will be stuck for? Some of the refugees are teaching and others looking for ways to make life less sterile.”

The response to the crisis from most western governments shames him and he says it’s highly likely a fresh wave of migrants will emerge from Africa following the recent declaration of famine in South Sudan and on-going conflicts elsewhere.

Five hundred miles east of Leros, Gaziantep in south-east Turkey, has the feel of a modern city.

Yet this air of normality masks underlying dangers such as people smuggling and sex slave trading. If rumours are to be believed, it’s also a haven for operatives for the so-called Islamic State (IS).

The city lies just 97km north of the recently besieged Syrian city of Aleppo. And it’s to this strategically placed Turkish centre that Angus and Perthshire-raised aid worker Craig Cowan has journeyed twice over the past year while working for one of the world’s biggest aid agencies, Mercy Corps.

As an assistant project officer at the charity’s European headquarters in Edinburgh, his primary role is to support field teams across the Middle East.

But around 30% of his work is in the field and he has visited Gaziantep twice to help co-ordinate activities on the ground.

There’s no shortage of work to be done. According to the United Nations, 4.8 million people have fled from the war in Syria since 2011 with a further 6.6 million displaced within their own country.

“The situation facing thousands of refugees within Syria is dire,” explains Craig, 28, an Edinburgh University business studies graduate and former pupil of Blairgowrie High School who grew up on farms in Angus and Perthshire.

“Our job is working with refugees inside Syria – people displaced by fighting and helping them get back on their feet. Most of them are desperate to get back home. So it’s very frustrating when the bigger picture, over which we have no control, prevents this from happening.”

Aid work wasn’t Craig’s first choice of career – but it is the one he’s found most rewarding.

After graduating and travelling in South East Asia, he worked in Glasgow for financial consultant Deloitte.

The money was good but his heart wasn’t in the business world and he decided to do a masters’ degree in international development at Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

He went on to complete a TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) course in Bangkok, followed by a spell working with a United Nations agriculture project in Rome before securing his job at Mercy Corps in early 2016.

So why does he do it?

For Craig, it’s a strong desire to fight poverty, injustice and make positive change in the world. He and his colleagues regularly need to come up with creative solutions to some of the world’s toughest problems and that’s a challenge he simply wouldn’t get in other lines of work.

“We give people the tools to help them bounce back,” he explains.

“We also run programmes that give them the skills and chances to become entrepreneurs and give their children a basic education.

“It’s very difficult when frontiers and access change. There wasn’t a lot we could do to help people inside Aleppo, for example. But a lot of people have told us that Mercy Corps is their only hope.”

The beheading of Perthshire aid worker David Haines by IS in 2014 was a harsh reminder of the potential risks facing those who trade their own comforts to help others.

Fife man David Hamilton, a serving Police Scotland sergeant who is vice chairman of the Scottish Police Federation, knows all about the potential dangers of delivering aid to the world’s trouble spots.

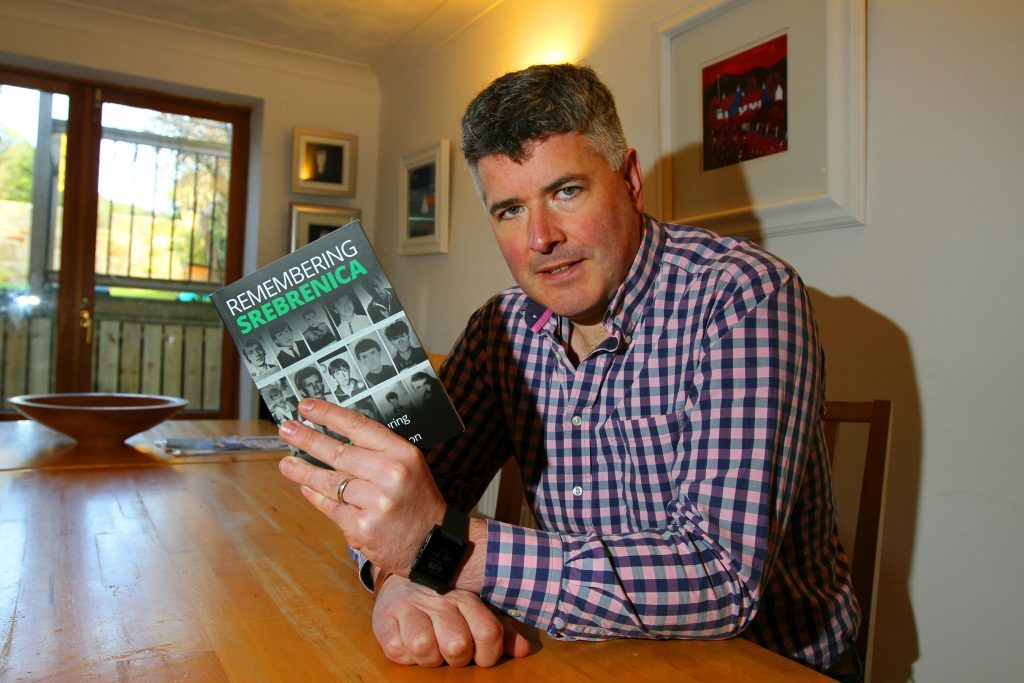

The founder of the charity Remembering Srebrenica Scotland, who sits on the committee of relief agency Edinburgh Direct Aid, drove relief lorries to Sarajevo during the four-year siege of the city by Bosnian Serb forces in the 1990s.

He and fellow volunteers often found themselves under heavy gun fire while “siege busting” to deliver food, clothes and medical supplies to civilians most in need.

David, 45, of Letham, remains shocked by the genocide that happened in Srebrenica 22 years ago and now leads high profile delegations to the Balkans to keep the massacre of thousands of innocents in the public eye.

For him, the crusade has deep personal roots. His mother-in-law Christine Witcutt was shot dead while leaving Sarajevo with an Edinburgh Aid convoy in 1993.

A memorial centre for children with special needs was created in her name in Sarajevo, and it was at the centre’s opening in 2001 that he first met Christine’s daughter Julie – now an occupational health nurse at Ninewells Hospital in Dundee – who went on to become his wife.

“My father-in-law Alan, who I knew through aid convoys, always says ‘Sarajevo is a place I lost my wife and gained a son in law’,” says David, who first volunteered as an aid convoy driver in 1994 after becoming disillusioned with a travelling salesman’s job aged 22.

“It’s a strange place. It has a lot of mixed memories for us all. When I was there we were getting shot at, bombed, there was no water or electricity. Every time I go back now, it’s really odd.”

Now a father to Holly, 8, and Rory, 6, he has remarkable stories of aid convoys being shot-up in an area of Bosnia known as the “shooting gallery”.

He recalls the defiance of civilians who were under siege, including the residents of one town who took all the washing machines out of their houses and put them on rafts in the river to inversely generate electricity.

The purpose was to power the street lights so that locals could “promenade” at night. “They had no food or nothing. But for them promenading was the most important act of defiance, to keep their spirits up,” he says.

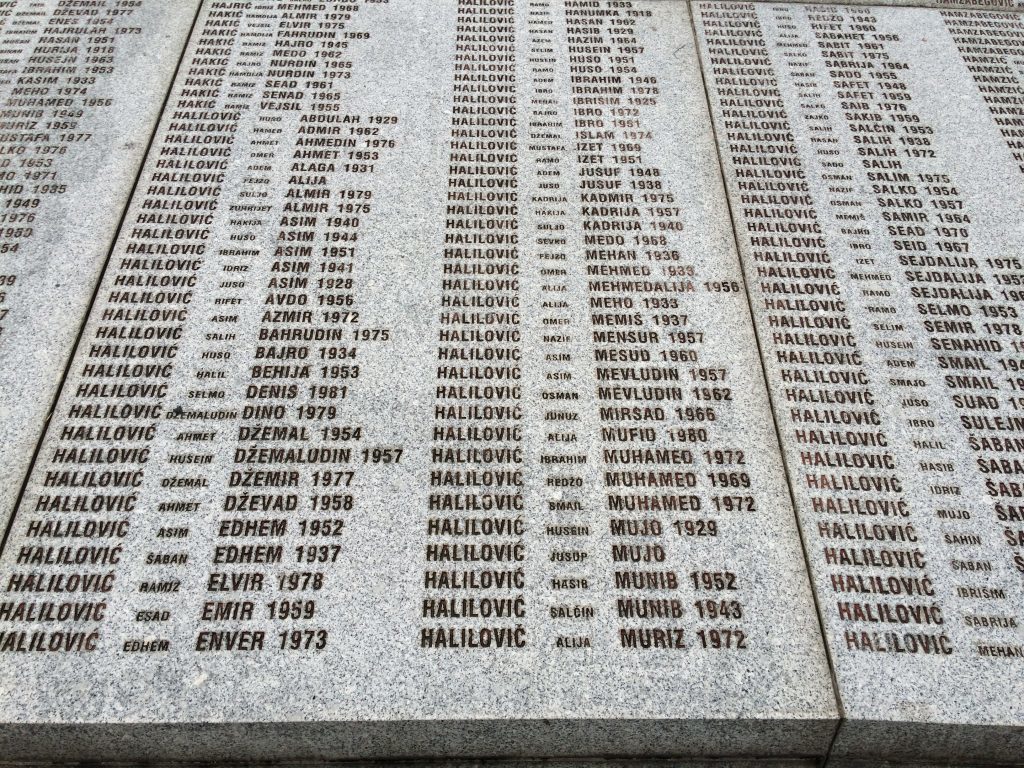

It was only years later that the full extent of the summer 1995 genocide became apparent when General Ratko Mladić and his Bosnian Serb forces marched into the town of Srebrenica and systematically murdered 8372 Bosnian Muslim men and boys.

Since then, efforts have been made to bring perpetrators of war crimes to justice and an incredible amount of rebuilding has taken place thanks largely to European Union money.

David has helped repatriate refugees who, just years earlier, had been thrown out by their machine gun-wielding neighbours and sent to concentration camps.

He remains worried about the future. Survivors tell him that centuries-old ethnic tensions are again on the rise against a backdrop of chronic unemployment, corruption and a failing economy.

Hate speak in the Balkans is being “normalised” and he has deep concerns about the anti-refugee rhetoric now prevalent across Europe and the USA.

“Somehow we don’t seem to learn our lesson,” he says.

“The Brexit stuff here was awful – absolutely disgraceful – and it fuelled a latent, narrow-minded view among many people who don’t know any better.

“The message from Remembering Srebrenica is that it’s not alright to think that. That’s the challenge for us in this charity, and that’s why we are going into schools to help pupils think about these issues. Genocide was never meant to happen again but it did. We need to do what we can to ensure history doesn’t repeat itself.”