Sixty years since Britain became a thermonuclear ‘superpower’, could the use of such weapons ever be justified? Michael Alexander looks at both sides of the debate.

Sixty years ago on the evening of November 8, 1957, a scientific test over a tiny atoll in the Pacific changed the course of British history.

At 5.47pm GMT, whirring high above Christmas Island in Kiribati, an RAF Valiant dropped a bomb 100 times more powerful than that which had devastated Hiroshima 12 years earlier.

The bomb, codenamed Grapple X, took 52 seconds to fall, and when it did, Britain’s first successful test of a megaton hydrogen bomb – coming five years after the UK’s first nuclear test in Australia – rendered the country a nuclear superpower for the first time.

Six decades on, and more than 25 years after the end of the Cold War, debate about nuclear weapons is as topical as ever in a week when US President Donald Trump has described North Korea’s nuclear missile program as a “threat” to the world.

Today, it’s thought nine countries together possess around 15,000 nuclear weapons.

The US and Russia maintain roughly 1800 of their nuclear weapons on high alert status – ready to be launched within minutes of a warning.

The UK is said to have a stockpile of around 215 thermonuclear warheads while somewhere in the North Atlantic at least one of Britain’s four nuclear, Vanguard-class submarines is always patrolling, ready to launch the £167 billion Trident nuclear weapons system if instructed by the Prime Minister.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ul8TbSbVGzY

But as debate about the alleged health effects of British nuclear testing in the Pacific continues amid an on-going legal battle, could the destructive power of the modern weapons system, capable of bringing Armageddon to the world, ever be justified?

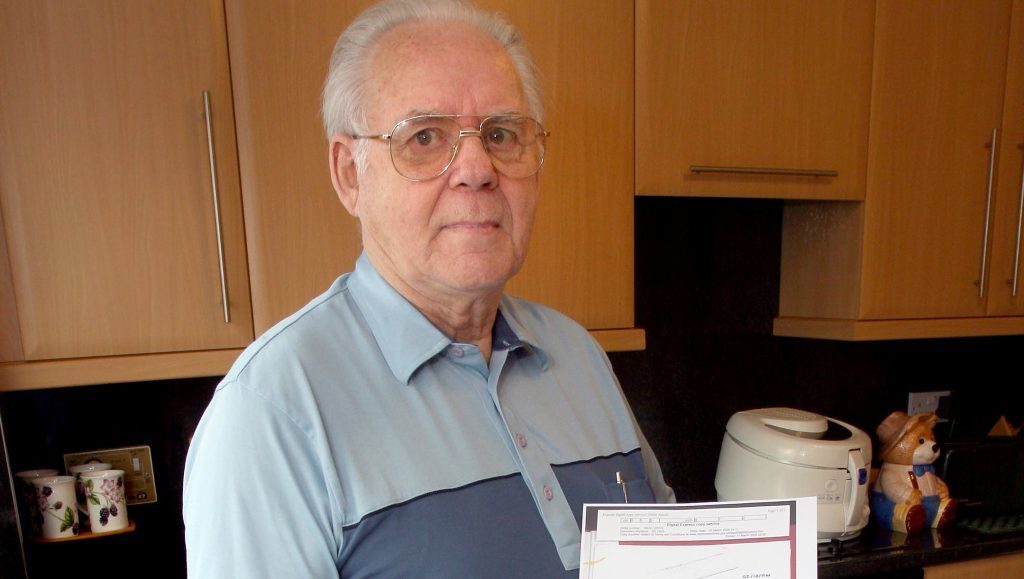

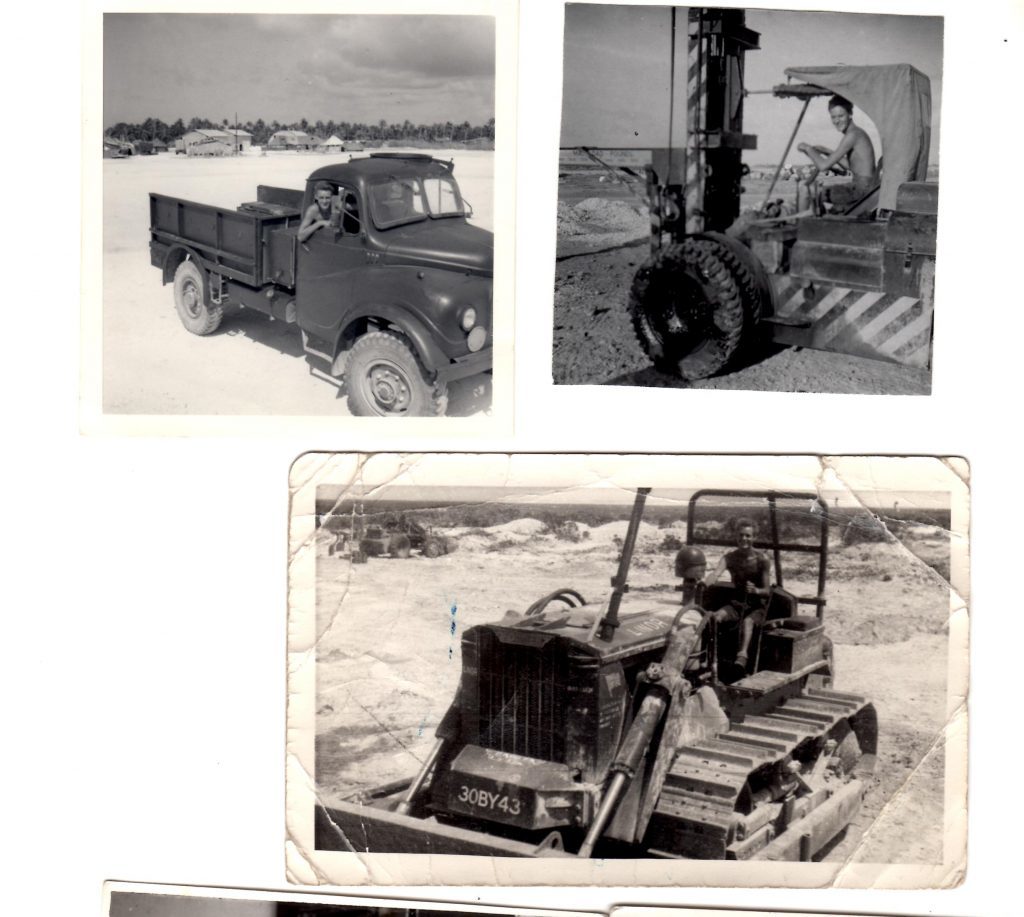

Fife pensioner Dave Whyte, 81, of Kirkcaldy, who claims he suffered sterility and genetic damage through radiation exposure during the British hydrogen and atomic bomb tests at Christmas Island in 1958, says the world is now “stuck” with nuclear weapons – and he fears “Armageddon” in future.

“I was not at Grapple ‘X’,” he said, “but did witness the hydrogen bombs Grapple ‘Y’, ‘Flagpole and Halliard. I also witnessed atomic bombs Pennant and Burgee in 1958.

“As a Sapper, I found the bombs very interesting. It was wonderful to view two suns shining in the sky at the same time, our usual golden sun and the red glow of fire from the nuclear bombs.

“It is said, by many, that nuclear bombs should be abandoned. Unfortunately, the technology is now available, and any ‘rogue’ state can develop their own nuclear weapons. North Korea is a good example, they have the weapons now, and will be prepared to use them.

“Great Britain has a nuclear arsenal, but at what cost? The veterans who helped in the nuclear experiments are cast aside, and are still waiting for a court to hear their case.

“They are denied legal aid to pursue their cause, whilst criminals, illegal immigrants etc get legal aid.

“There is a blood test which shows the level of radiation a person has received: Nuclear veterans are denied this test, even the offer of paying for the test is denied.

“Documents showing the true levels of radiation individuals received are hidden from view, and directions given by the judge to release them are ignored.

“Sadly, we have nuclear weapons and we cannot dispose of them now. I foresee an ‘Armageddon’ in the future.”

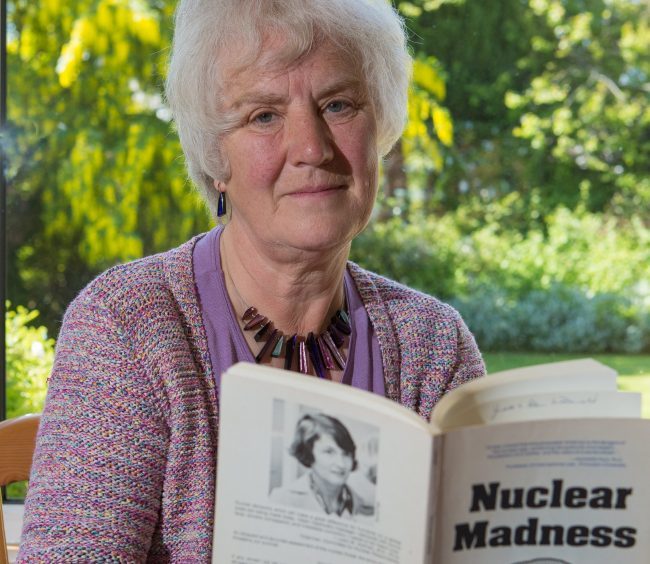

Former St Andrews woman Dr Judith McDonald has been at the forefront of Britain’s nuclear disarmament movement since the early 1980s.

The Comrie-raised Aberdeen University medical graduate, who became a co-founder of the Medical Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (MECANWE), says there’s now never been a more important time to take a stand against the “madness” of nuclear weapons.

“There can be no doubt about the catastrophic humanitarian and environmental consequences of nuclear weapons,” said the former Cupar GP.

“Recent tensions between North Korea and the USA have reminded us that the risks of these weapons of mass destruction are still very much present. Sooner or later they will be used, either by accident or intent.

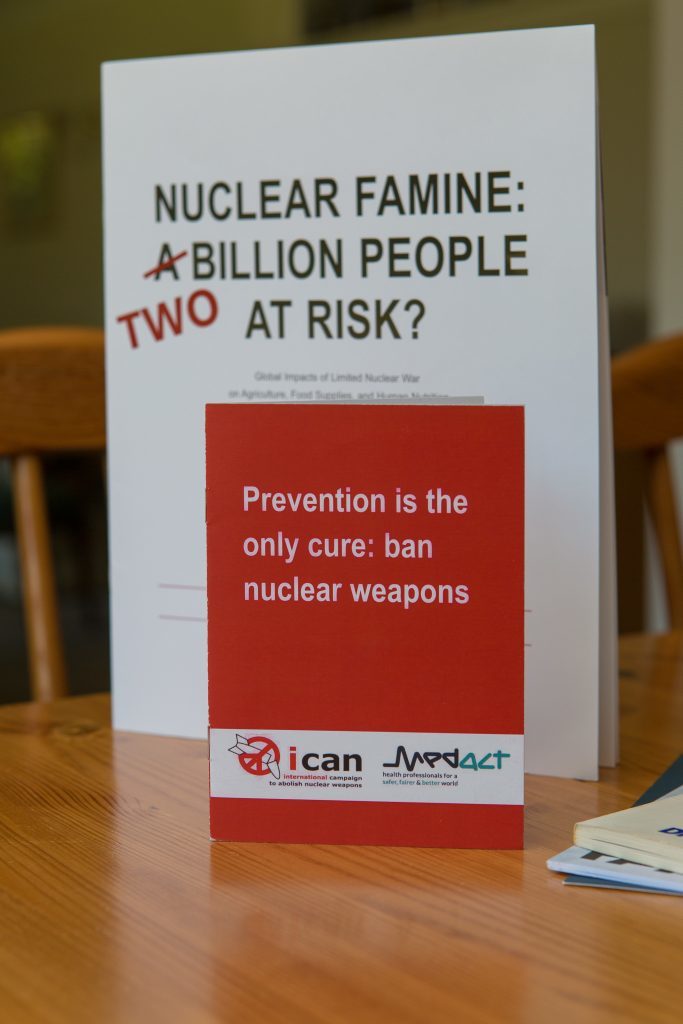

“2007 saw the launch of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), a global, civil society, grassroots movement working towards a ban on nuclear weapons.

“Central players in this have been the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) and the International Committee of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (ICRCRC) both of whom have made it clear that there could be no effective relief effort in the event of a nuclear war.

“On July 7 this year the United Nations adopted a Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons supported by 122 countries. This opened for signing on September 20.

“Most significantly, on October 6 of this year ICAN, which represents over 400 NGOs in 101 countries, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, which will be presented in Oslo on December 10.”

Earlier this year the then Defence Secretary Michael Fallon said the Prime Minister Theresa May would fire Britain’s nuclear weapons as a ‘first strike’ if necessary.

He said she was prepared to launch Trident in “the most extreme circumstances”, even if Britain itself was not under nuclear attack.

“Our retention of an independent centre of nuclear decision making makes clear to any adversary that the costs of an attack on UK vital interests will outweigh any benefits,” the Ministry of Defence states.

However, the MoD adds that the UK is a “responsible nuclear weapon state” and party to the Treaty on the Non Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

The UK also remains committed to the long term goal of a world without nuclear weapons, having reduced its own nuclear forces by over half from their Cold War peak in the late 1970s.

“By the mid-2020s, we will reduce the overall nuclear weapon stockpile to no more than 180 warheads, meeting the commitments set out in the 2010 Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR),” the MoD says.

Mid Scotland and Fife Conservative MSP Liz Smith said: “The successful test of Grapple X resulted in the UK becoming the world’s third nuclear power and was an important milestone during the early Cold War.

“It was an event that showcased British technological prowess and those involved in the project were amongst our best and brightest and it’s important that we commemorate their achievement.

“Since then, the UK has retained an active nuclear deterrent which has played an vital role in protecting our interests and citizens around the globe.

“In an uncertain world it is important that we retain and renew our nuclear deterrent and polls last year revealed that this was a view shared by the majority of people in the UK.”