NASA space scientist Dr Sue Lederer, who recently embarked on an educational visit to Fife, tells Michael Alexander why human-made space debris are a reminder of Earth’s fragility – and a potential hinder to longer-term human progress in space.

Ask an astronaut which Hollywood depiction of space has annoyed them most in recent years, and the chances are it’ll be Gravity.

It’s the unrealistic way the scenes are portrayed whereby rocks hit an astronaut, the astronaut flies off into the emptiness of space only to be saved by her commander who just happens to be George Clooney.

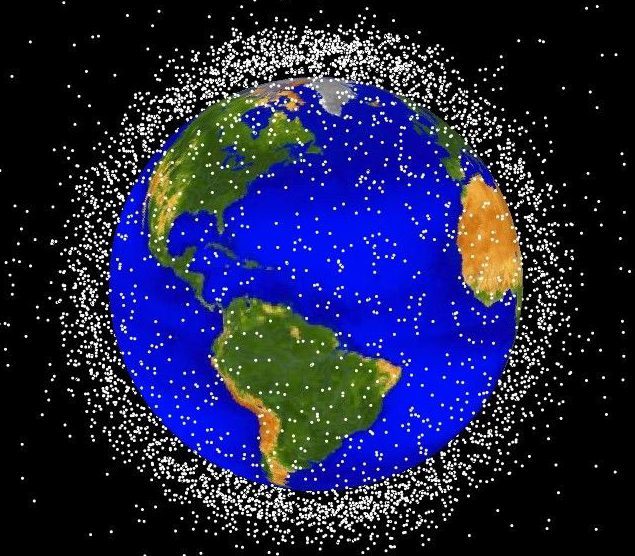

But what is realistic about the growing man-made debris field in orbit around Earth is that it can have a huge impact on every mission in space, as well as satellite activity.

It’s estimated that since the launch of the Soviet Union’s Sputnik satellite in 1957, space exploration has produced an estimated 170 million pieces of space junk that are currently in low Earth orbit – and this growing amount of space debris could lead to catastrophic collisions with satellites.

The debris in space can travel at speeds above 27,000kmh, which is fast enough for even a small fragment to damage or destroy satellites.

Just the other month it was announced that there’s now so much junk in orbit that the International Space Station (ISS) has been forced to install a sensor to detect when it gets hit with bits and pieces of artificial space junk.

The new sensor, which is called simply the Space Debris Sensor (or SDS for short), is designed to monitor any impacts caused by the smaller, untraceable bits of space junk that are simply too tiny for NASA to monitor.

The SDS is firmly mounted on the exterior of the International Space Station, where it will remain for up to three years, giving scientists an idea of just how much garbage is colliding with the orbiting laboratory on a regular basis.

A mission is also being prepared that will test different methods to clean up space junk.

The RemoveDebris spacecraft, assembled at Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL) in England, will attempt to snare a small satellite with a net and test whether a harpoon is an effective garbage grabber.

The probe will soon be packed up ready for blast off early in 2018.

Space scientist Susan Lederer, who is based at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, works in NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office.

She recently she spoke to Fife school children at St Andrews University about the scale of the space debris problem, and now, in an interview with The Courier, she explains why space needs to be kept clean for the sake of humanity.

“Each individual piece of debris is so small that they aren’t viewable in images of the Earth from space, just like one is unable to see all the floating plastic bottles and bits littering the oceans or even the boats when you take a photo of Earth from space,” she says.

“Rather, knowing how delicate the ocean’s ecosystem is to the pollutants created by humans is a reminder of how important, too, the shroud of space surrounding the Earth is –we must take care of space, too, if we are going to continue to be able to use this precious resource for humanity.”

Dr Lederer often travels to Chile to collect data with telescopes.

She is the Principle Investigator (PI) of the 1.3-meter MCAT telescope, which she helped build on Ascension Island (between Brazil and Africa) in 2015 for observing debris.

As a planetary scientist, she conducts hypervelocity impact experiments with the Experimental Impact Laboratory (EIL) at NASA JSC to study how collisions between asteroids and collisions between comets affect their surfaces.

She was involved in the Japanese spacecraft mission Hayabusa, which imaged and sampled the surface of asteroid Itokawa.

She was also part of an international team of scientists who studied Comet Tempel 1, the target of the Deep Impact Spacecraft mission, which successfully impacted the surface to create a crate.

She was also part of the team that discovered three Earth-sized planets around another very nearby, very small, red star called TRAPPIST-1, and one or more of those planets just might be suitable for life to form – maybe!

Like many of her colleagues, she too was excited by the recent 45th anniversary of the famous ‘Blue Marble’ photo of Earth taken by the crew of Apollo 17 on their way to the moon on December 7 1972.

However, she says lessons about the fragility of Earth must be learned.

She adds: “The early NASA photos of the Earth gave humanity a perspective unlike any before, creating a paradigm shift in how we see ourselves and our home planet in this vast universe – we are but one of many, and yet are sole survivors in this part of space.

“Seeing the Earth almost as though you could hold it gently in the palm of your hand, humans must understand that we are not invincible, that to survive, we must take care of our precious and delicate environment within the harsh vacuum of space if it is to continue to foster our own existence in the universe.”