How has life as a 70-year-old changed between the post-First World War and post-Second World War generations? Michael Alexander looks at the statistics.

When the generation born after the Second World War was starting to make its way in the world, it was a time of relative and fairly effortless prosperity.

They were the first to benefit from 20th century developments such as ‘cradle to grave welfare’.

And they have lived through a period of unprecedented economic, social, cultural and technological change.

But with the so-called “Baby Boomer” generation now in its early 70s, how do their fortunes at that age compare with the generation that came before them – the baby boomers who were born at the end of the First World War?

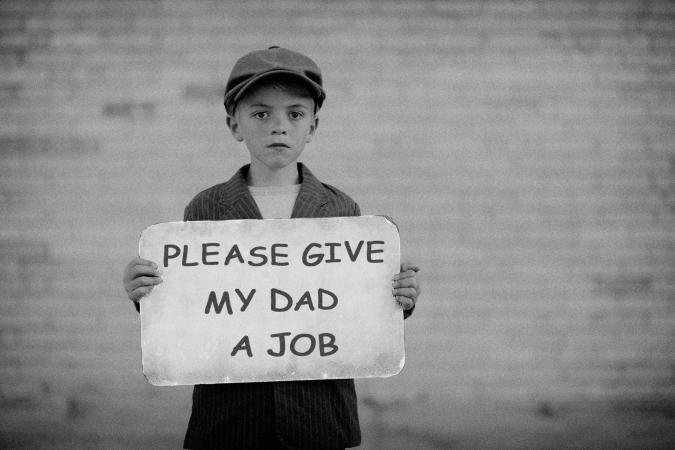

How do standards of living with the post-Second World War generation compare with the generation who lived through the Great Depression of the 1930s, who were young adults during the Second World War and who turned 70 in the early 1990s just as recession hit the UK?

According to statistics published this week by the Office for National Statistics, despite there being fewer than three decades between these generations, there are significant differences in life expectancy, marital status, childbearing, and employment.

The number of people in their 70s in the UK increased from four million to five million between 1990 and 2016.

Thanks to the creation of the NHS and cessation of European wars, survival was far better for the post-Second World War baby boom generation (born 1946) than those born following the First World War baby-boom (born 1920).

For example, only 58% of babies born in 1920 survived to age 70 in 1990, compared to 78% of babies born in 1946 who turned 70 in 2016.

With increases in survival have come increases in life expectancy.

Life expectancy at birth for women pushed through the 70 age barrier in 1950, while men had to wait until 1977.

Having got there, the figures suggest that today’s 70-year-olds are also more likely to live longer than their predecessors, particularly men.

Based on mortality patterns in 2016, and leaving regional variations aside, men aged 70 can now expect to live for a further 15.3 years, up from 11 years in 1990. For women this is 17.3 years, up from 14.3 years in 1990.

Increases in life expectancy have been linked to reductions in smoking and circulatory disease.

Meanwhile, increases in life expectancy between 1991 and 2016 mean that more men survived into their 70s.

“Only 30% of women in their 70s were widows in 2016, compared to 49% in 1991,” the report says.

“This may help explain the increase in the proportion of women who are married (from 40% to 55%), as well as a climb in the number of older people who are divorced; a three-fold increase to 9% of men and a four-fold increase to 12% of women.”

Marriage rates were higher for men aged 70 to 79 than their female counterparts, possibly because men tend to marry younger women. And marriage rates were higher for divorcees than single or widowed people.

The figures also reveal that today’s 70-year-old women are far less likely to be childless than the previous generation; childlessness halved from 21% to 9% of women between 1990 and 2015.

Higher levels of childlessness among women turning 70 in 1990 are thought to be associated with the relatively harsh times that they lived through.

They experienced the shortages of the Great Depression in childhood and hit fertility during the turmoil of the Second World War during which many young men died, resulting in a deficit of potential husbands.

As a result, today’s 70-year-old women are more likely to have children to support them in old age than a generation earlier.

While fewer women are childless at age 70, they are less likely to have large families (four or more children) than in the past, and more likely to have just two or three children.

Regardless of the reasons for increased employment, people in their 70s today also tend to be more financially secure than in the past.

The figures show that the employment rate for people aged 70-79 doubled between 1992 and 2017, from 4% to 8%

Some 82% of people in their 70s now report their financial situation as ‘doing alright’ or ‘living comfortably’ compared to 52% in 1991.

They benefitted from large discounts on council houses, resulting in a rapid expansion in home ownership; in the early 1980s.

This compares with people turning 70 in 1990 were in their early 60s at that time and would have found it more difficult to secure a mortgage.

But the improved fortunes of baby boomers have not been without controversy.

By contrast, the signs are that Millennials (those currently aged 20 to 35) face far greater economic challenges with less secure well paid employment, rising living costs, poorer pensions and fewer prospects.