A Canadian government agency is commemorating the loss of the last merchant ship sunk by Germany – off the coast of Fife – just minutes before the official end of the Second World War.

Pascale Guindon, National Programs Coordinator at the National Celebrations & Commemorations Branch of Parks Canada, told The Courier that he was researching the loss of the SS Avondale Park as part of a broader project called Home Port Heroes.

The initiative by Parks Canada – a federal agency which preserves and presents places of national cultural and ecological importance – honours the men and women who built the ships of Canada and Allied merchant navies, and those who sailed them through war zones for the cause of freedom.

Mr Guindon recently read The Courier’s article from May 2015 which reported the unveiling of a memorial in Anstruther.

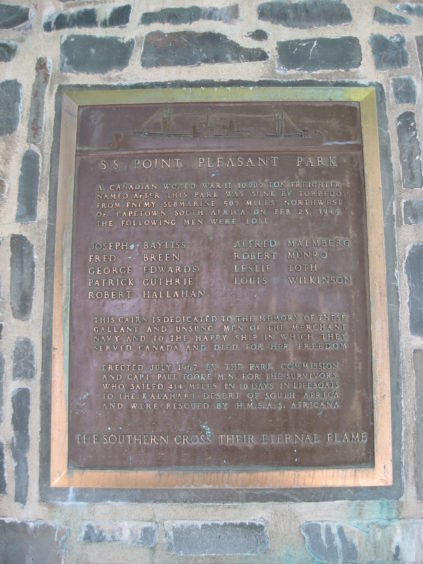

He said: “The memorial is very similar to one for another torpedoes ‘Park’ merchant ship, SS Point Pleasant Park.

“The memorial is located in its namesake park in the City of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

“Halifax was a significant Allied port where merchant convoys would gather before crossing the treacherous north Atlantic and the Province of Nova Scotia is where Avondale Park was built.

“I find these kind of intercontinental links fascinating – the Allied Merchant Navy travelling to just about every continent during the war.”

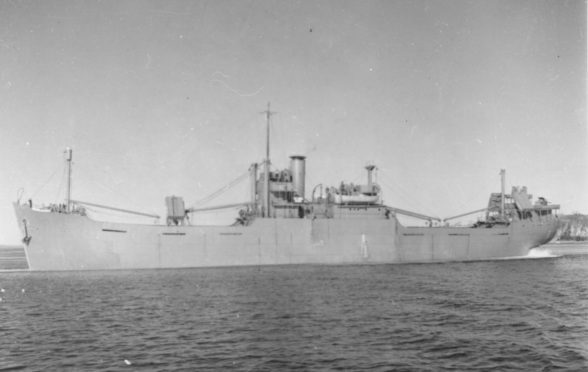

At 10.40pm on May 7, 1945, the cargo ship SS Avondale Park, built in Pictou Nova Scotia, and on passage from Hull to Belfast, was sunk in convoy 1.5 miles south east of the May Isle in the Firth of Forth.

The torpedo was fired by the Type XX111 German submarine U2336 commanded by Kapitanleutnant Emil Klusmeier.

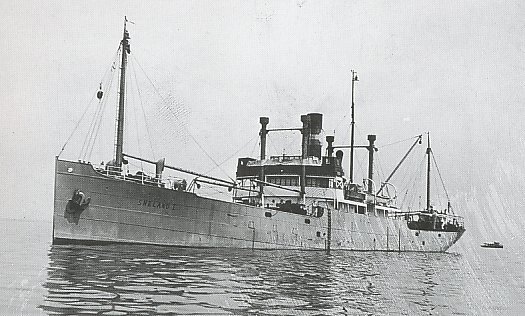

Another torpedo sank the Norwegian ship, Sneland1.

Within minutes, the war in Europe ended.

U2336 was depth charged by the convoy escort, but escaped in the early hours of VE Day, May 8, 1945.

Chief engineer George Anderson and engine room donkeyman William Harvey died when the torpedo struck the Avondale Park’s engine room.

On Sneland 1, seven men were killed— Captain Johannes Laegland, Alf Berenson, Tormod Ringstad, Otto Skaugen, Simon Johanson, Nils Konradsen and William Ellis, aged 17, of Hull.

These were the last sinkings by a U-boat in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Those lost in this attack were amongst the most poignant and pointless casualties of all.

The order for U-boats to cease hostilities had been given three days earlier by Reichsadmiral Doenitz.

However, Kapitanleutnant Emil Klusmeier of U2336 claimed the ceasefire order had never been received.

Some 35000 British and allied merchant seamen lost their lives between the sinkings of the RMS Athenia in 1939, and the SS Avondale Park, in 1945.

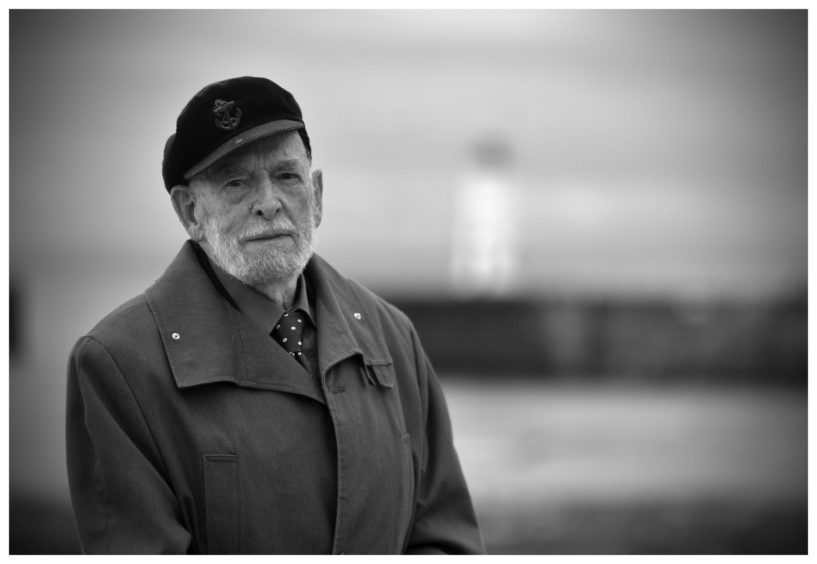

At the Anstruther plaque unveiling in 2015, 87-year-old Sydney Rapley of Dorking, Surrey, who was a 17-year-old cabin boy aboard the SS Avondale Park, told The Courier how he had forgiven the commander of the German vessel for the sinking.

In an exclusive interview, Mr Rapley, said: “We had sailed from Cardiff to Belfast. The first hold was full of coal, the second full of oil cake and the other two full of newsprint.

“We sailed to Loch Ewe and from there received orders to sail to Hull. There were five or six ships in convoy.

“We had come down through the Pentland Firth and on the evening of May 7 I took the helmsman a cup of cocoa and biscuits. They always let me take the wheel whilst they had a few minutes’ break.

“I went back to my cabin to sleep. I was reading the Readers’ Digest when the torpedo hit. I got blown up out of my bunk. I was on the top so hit the roof. I only had my underwear on! I grabbed my oil skin bag that had my ID and stuff in it and went on deck to get the lifeboat.

“I looked over the side and there was a massive hole with water gushing into the engine room. There was smoke and steam everywhere. I thought no one could survive that but the stokers got out.

“We got to the lifeboat and I always remember an able seaman appearing at a large port hole that was about to go under. He swam through it like a porpoise!

“We were picked up by a Royal Navy vessel 15 minutes later. There we did a headcount and realised two were missing.”

Sydney, who went on to work as a plasterer and raise a family after the war, said he had felt “very unhappy” about the tragedy for many years.

However, as time wore on, he forgave the German commander who claimed he never received orders from the authorities to ceasefire.

“It’s very sad really. It’s amazing to think my cabin and my old record player is still out there.”