A Second World War veteran who pulled bodies out of the River Tay after seven fully-laden paratroopers dropped to their deaths during an exercise 75 years ago has spoken of the “sadness” he experienced after the recovery operation.

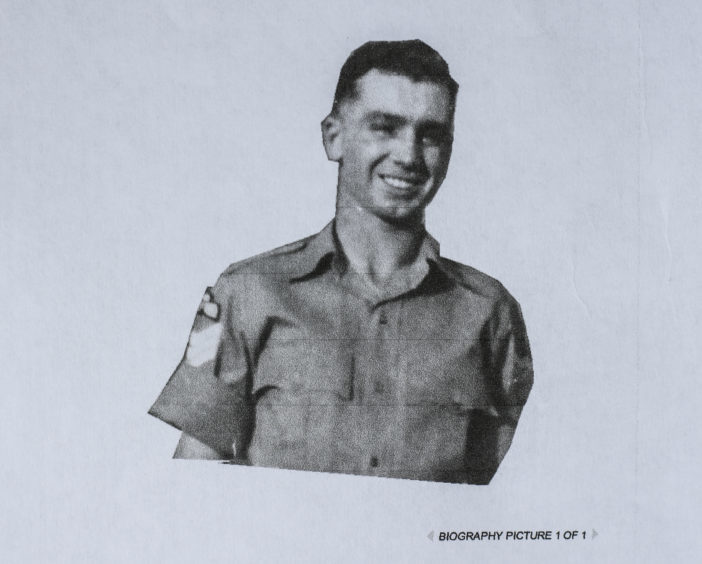

James Stewart, 97, of Dundee, was a senior aircraftsman with the RAF, stationed at Tayport, when, following the events of June 13, 1943 at Wormit Bay, he was tasked with launching his boat to recover several of the bodies that had been spotted flowing down river with the tide.

Mr Stewart was in charge of one of the RAF launches at Tayport when a message was received requesting his crew’s assistance to recover the bodies as they drifted towards the sea.

“It was one of the Fifie guys at Newport who got in touch,” said Mr Stewart, speaking from the sheltered housing complex where he now lives in Dundee.

“They had seen the bodies floating by but there wasn’t enough water for them to go out and recover them.

“So they contacted us situated down at Tayport. I was in charge of the RAF launches. I knew the area quite well and the Fifie guys had given us a good idea where the bodies were.”

Mr Stewart, who contacted The Courier after reading our 75th anniverary coverage this week, said they had no advance knowledge of the top secret exercise, which was preparing for D-Day.

However, working with the RNLI boat from Broughty Ferry, they knew immediately that they were dealing with a recovery rather than a rescue operation.

“Hitting the water with parachutes on at that speed, we knew they’d have broken their necks instantly,” he said.

“Some of us had to go into the water when we found the bodies to put ropes around them and pull them out. That was a difficult task given they were laden with kit and water. But we managed to get two out. Several of the others washed up over time.”

The Courier revealed on Wednesday how Anna Mulford – the late mother of Dundee-raised former Courier, STV reporter and RAF Public Relations Officer for Scotland Michael Mulford – witnessed the seven fully-laden paratroopers being dropped to their deaths during the exercise over Wormit Bay.

The men, training for the D-Day landings a year later, were supposed to be dropped 10 miles to the east at Tentsmuir as part of a top-secret exercise to see if paratrooper could be dropped into a tight space.

However, for reasons unknown, two of the 10 converted Whitley bombers that had flown from Salisbury Plain carrying 130 troops, veered around the coast towards Wormit and offloaded their men from an altitude of 800 feet into around 30 feet of water west of the Tay Rail Bridge.

The second aircraft over Wormit contained nine men from the 8th (Midlands) Battalion of the Parachute Regiment. Seven drowned, one refused to jump after seeing his colleagues’ fate and was court-martialled. The ninth, Regimental Sergeant Major Alan Parsons, landed on a narrow sandbank and made it ashore.

Another paratrooper died at Tentsmuir when he was struck during the jump by an ammunition box. Many others were injured.

Gauldry man Peter Carmichael told The Courier how his late father Peter rarely talked about his role in rescuing Sergeant Major Parsons from the sandbank in the Tay because it was a “taboo subject”.

Mr Carmichael told how his father, who lived in Balmerino, rescued Regimental Sergeant Major Parsons from a narrow sandbank – just yards from where seven of his paratrooper colleagues had drowned.

Water was up to the paratrooper’s neck when he was plucked to safety.

“My father who stayed in Balmerino at the time went out with another chap called Robert Collier,” Mr Carmichael said.

“I can remember my father saying that when he got to him the water was lapping at his neck.

“He rarely talked about it because it was very much a taboo subject.”

Meanwhile, jumping from an aircraft at 800 feet is still the standard drop height for static jumps by paratroopers on covert military operations, according to Retired Squadron Leader Keith Wardlaw, 70, of Perth – a former RAF parachute jumping instructor who was attached to the Parachute Regiment and Special Forces for 30 years.

Squadron Leader Wardlaw, who was charge of media and communications at RAF Leuchars for 12 years before retiring in 2012, told The Courier that parachute technology had changed during the intervening years.

However, the basic round canopy concept remained the same.

“Nowadays they’d use LLPs (Low Level Parachutes),” he said, “whereas at that time it was an X-type parachute which had a tendency to oscillate. They also jumped without reserve chutes in those days.”

Squadron Leader Wardlaw said an aircraft on such a mission today would fly below 200 feet to stay below radar. Then about two minutes from the drop zone, when it hit the “tactical approach point”, it would rise to 800 feet for the “run in”. At that point the troops in the back would prepare for the jump with the pilot or navigator controlling the red and green ‘jump’ lights.

“I can’t say too much about what happened back then,” he said, “but it suggests there must have been a navigational error.

“Nowadays when training takes place parachute instructors will fly with them, check their equipment, call action stations and jump with them.

“Today, they would also jump out the back or side of an aircraft rather than through a hole in the floor”.