As the nation reflects on the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War on November 11 1918, prominent businessman Sir Michael Nairn tells Michael Alexander about the family tragedy that directly led to the gifting of Kirkcaldy Galleries and war memorial to the town.

It was the family firm that launched its floor cloth factory in 1847 before leading Kirkcaldy to become the linoleum capital of the world.

But 50 years after Michael Nairn and Co Ltd ended its association with the lino industry, a gift to the town born out of a Nairn family tragedy is being remembered this week as the country reflects on the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War.

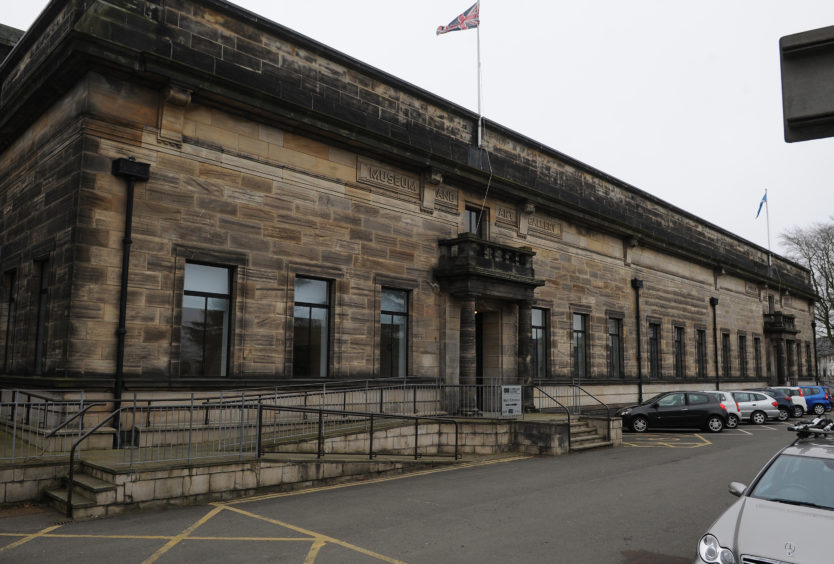

It’s 93 years since Kirkcaldy’s War Memorial and Museum & Art Gallery opened in 1925, with the library added in 1928.

They were gifted by the then chairman of the company John Nairn.

But that gift came at a tremendous personal loss.

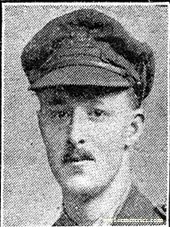

Along with the construction of the adjacent war memorial and memorial garden, the building was gifted in memory of his only son Ian who was killed aged 25 while serving in the First World War.

Ian died only two months before the war ended while serving with the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry at the Somme – mown down by a German machine gun.

The events were remembered at a special reception held at the Kirkcaldy Galleries on Wednesday – and they will be in the minds of many when the Armistice Day events take place this weekend.

“Ian was killed on September 2 1918,” said Dundee businessman Sir Michael Nairn, 80, – a direct descendent of the first Michael Nairn.

“We thought it would be better to mark this occasion in what is effectively Remembrance Week leading up to the Armistice on November 11.

“But in all likelihood without Ian’s death, Kirkcaldy would never have got its museum.

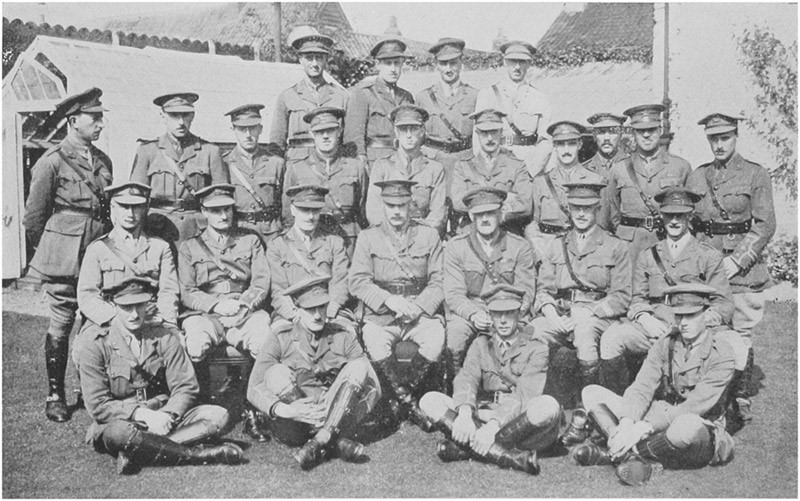

“It is right also to remind ourselves that 600 employees of the company including Ian and Robert, Robert Spencer-Nairn’s grandfather, left to fight in one or other of the services. Of those, over 80, leaving grieving families at home, did not return.”

The Nairn business was started in 1847 by the first Michael Nairn who came from a sail making background.

By putting sail cloth on the floor and painting it, it became a floor covering. Linoleum, as a much more substantial product, was invented 30 years later.

Michael Nairn’s son Michael Barker Nairn built the business and took it all over the world – developing factories in America, France, and Germany, as well as in Kirkcaldy where at one time they employed over 2000 people.

It was when he died in 1915, however, that his younger brother John took over as chairman – leading, just three years later, to the personal tragedy of war.

“John Nairn lost his only son,” said today’s Sir Michael, “and at the end of the war, like most towns in Britain, Kirkcaldy wanted to create a war memorial.

“Very generously John said as part of the war memorial he would contribute the cost of the building to house a museum and art gallery.

“Rather than just a plinth – which is the common thing with the names of the sons that were killed – Kirkcaldy got not only the memorial but this lovely building.”

Sir Michael explained that John Nairn was quite an art collector himself and contributed not only the building but a good part of the founding collection of art.

At a time when Kirkcaldy had developed as an industrial centre, the addition of a gallery and library to the town was a vital addition to its fabric.

“It just so happened that John Nairn – whatever genes were in him – they came out and he was very artistic,” added Sir Michael.

“When he was chairman of the business it was well recorded that one of his major contributions in a business sense was choosing designs of linoleum that would look good on the floor and sell well to the public in what was a competitive world to make the business a success.

“His contribution was more in the arts side than as a businessman. He was also a very retiring type. He wasn’t a self-publicist. He was a very shy man who preferred to be behind the scenes but was a very generous person who supported good causes in Fife and Kirkcaldy in particular.”

The son of the then chairman, Sir Michael, who served in the Black Watch, left to join the Michael Nairn company as it still was then in 1959 – working there for seven years.

Then in 1967 when the directors decided to sell the business to Unilever – leading to the company that continues operating today as Forbo Nairn – Sir Michael took himself off to the European Business School in France where he did an MBA in business management, going on to work for industry in London and Australia.

In 1978 he started his own business in Dundee called Rautomed – a metallurgical engineering company based at Wester Gourdie that builds electric furnaces for melting copper, gold and silver.

With the 40th anniversary of his own company and 100th anniversary of the ending of the Great War, he feels matters have gone “full circle” in more ways than one.

So how important is it to be marking the centenary of the Armistice?

“I’ve been thinking about that – it depends how old you are,” said Sir Michael.

“I’m 80. My generation was born between 10 and 20 years after the Armistice. To us it’s all very poignant. We had grandfathers and fathers who fought in the First World War, so for us it isn’t really history.

“It’s closer than that. For the younger generation growing up now. They get taught history at school.

“If they are seriously interested they can read about it. It hasn’t got the same relevancy or poignancy as it does for our generation. It depends how old you are.

“But three years ago a few of us went on a tour of Flanders and Northern France. I was struck by how beautifully kept the war graves are. The other strung that struck me was how many young people were visiting them.

“I think it is important to remember. And at least a proportion of young people are seriously interested.”