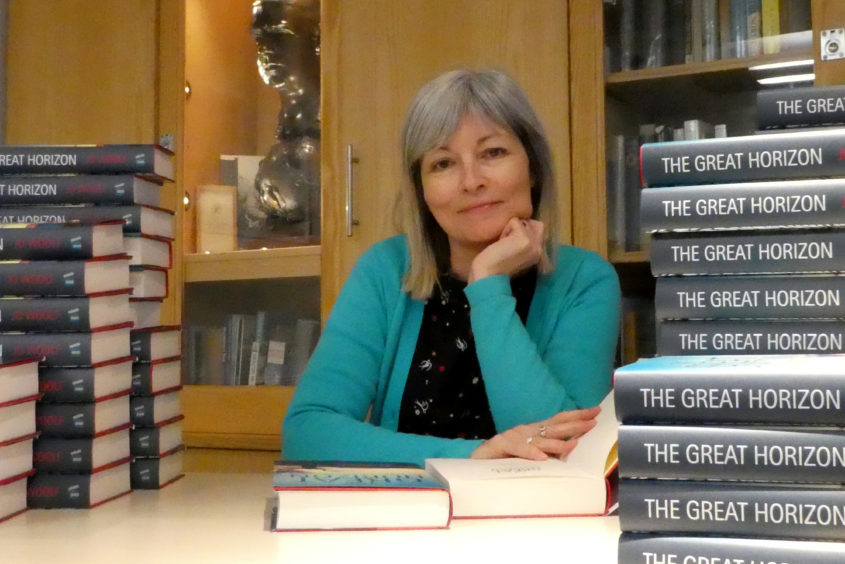

To mark the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landings, Jo Woolf – writer in residence at the Perth-based Royal Scottish Geographical Society – looks back at Neil Armstrong’s visit to Scotland in 1972.

Fifty years ago, on July 21 1969, Neil Armstrong made history by becoming the first human to set foot on the moon.

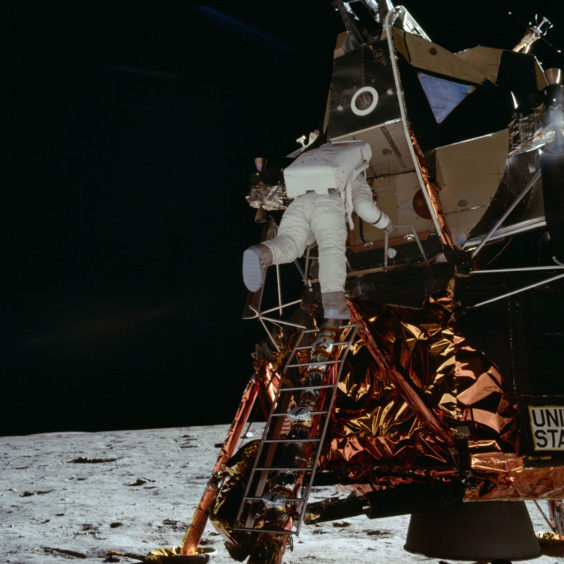

As the commander of NASA’s Apollo 11 mission, he climbed down the ladder from the lunar module Eagle, and was followed shortly afterwards by fellow astronaut Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin.

Around the world, millions of television viewers watched, mesmerised, as the pair appeared to skip lightly around the dusty landscape in their space suits; their bouncing gait was a result of the moon’s gravity, which is only one-sixth of that on Earth. Meanwhile, the third Apollo 11 crew member, Michael Collins, remained on board the Columbia spacecraft in orbit around the Moon.

When the astronauts returned to Earth, they were greeted with scenes of rapturous celebration.

Among the many honours that were awarded to Neil Armstrong was the Livingstone Medal of the Perth-based Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

The Scottish connection was particularly apt, as genealogists had revealed that Armstrong was directly descended from a Borders family: his ancestors emigrated to America in the mid-1700s.

On March 10, 1972, newspapers confirmed that Neil Armstrong and his wife, Janet, had arrived at Edinburgh Airport the day before.

Their flight had been uneventful, apparently, but from the air “he saw nothing of Scotland because of low cloud, and had a better view of the Moon when he brought down the lunar module.”

Nevertheless, a warm welcome was awaiting them at the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

After an informal dinner, Armstrong gave a talk in Edinburgh’s Usher Hall and was formally presented with the Livingstone Medal, an honour which he acknowledged with typical modesty.

Records show that he began his talk by repeating “a seemingly meaningless and wholly alien exchange between the lunar module and Mission Control, which nowadays has a much more familiar ring to it.”

It is interesting to speculate whether this was the now-iconic conversation immediately before touchdown, concluding with Armstrong’s famous words: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Communication featured strongly in Armstrong’s speech the following evening, when he delivered the Mountbatten Lecture at Edinburgh University.

Taking as his theme ‘Change in the Space Age’, he spoke with authority on the latest satellite technology, and predicted that “we will soon have the ability to transfer any amount of information from any point to any other at any time.”

In the early 1970s it was television that was attracting the attention of young people; Armstrong revealed that the average 17-year-old in the United States had accumulated more than 20,000 hours of TV viewing, nearly twice the number of hours spent in the classroom.

With advances in technology, he foresaw that “complete libraries of books, films and tapes may become available to the home receiver on request,” and that satellites would replace the postal service in business transactions.

But knowledge, he warned, was not equivalent to wisdom: “Wisdom requires understanding, and the key to understanding is communication.

“Communication is the common denominator necessary to reason, to logic, to explanation, to interpretation. It behoves us all to learn to know and use it well.”

After these prescient words, Armstrong was looking forward to a day in Dumfriesshire for his next engagement, on March 11.

His destination was Langholm, where he had been invited to become the town’s first Honorary Freeman.

Armstrongs, as he well knew, had haunted the area around Liddesdale and Eskdale for many centuries; they were notorious reivers, and in Langholm there was, in fact, a 400-year-old law decreeing that any Armstrong found in the town should be hanged.

At the civic reception, the splendidly ermine-cloaked Provost, James Grieve, must have had a twinkle in his eye when he reminded Armstrong that his ancestors were rogues; Armstrong smiled broadly in response and offered his polite view that the Armstrongs had been dreadfully misrepresented.

Cheering crowds thronged the streets as the couple waved happily from a horse-drawn carriage, preceded by a pipe band playing a specially-composed piece called ‘Commander Neil Armstrong’s Moonstep’.

In the Old Parish Church, Armstrong solemnly repeated an oath to be a “true and faithful burgess of the borough of Langholm” and then gave a short but sincere speech. He appeared to be moved by the occasion: “The most difficult place to be recognised,” he said, “is in one’s own home town – and I consider this, now, my home town.”

A specially-named ‘Lunar Tartan’ had been woven by Esk Valley Knitwear in Langholm, incorporating the black, brown and grey colours of the lunar landscape with a dash of bright red to represent rocket flame.

A swatch of this tartan was presented to the visitors, together with a mohair stole in the same pattern for Jean Armstrong.

The couple made a brief visit to Gilnockie Tower near Canonbie, the 16th century fortress of Border reiver Johnnie Armstrong, who was hanged by James V in 1530; and then they departed for Drumlanrig Castle, where they were the guests of the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch.

Next morning, in the grounds of the Castle, Armstrong planted a Red Oak tree to commemorate his stay.

No one who met Armstrong or witnessed his visit is ever likely to forget it; and it seems that the pleasure was mutual.

Shortly after his return to Ohio, where he was Professor of Aerospace Engineering at the University of Cincinnati, Armstrong penned an appreciative letter to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, thanking them for their hospitality and personal touches which, he said, would ensure “warm memories for years to come.”