As the Bank of England marks its 325th anniversary, does cash have a future? Michael Alexander reports.

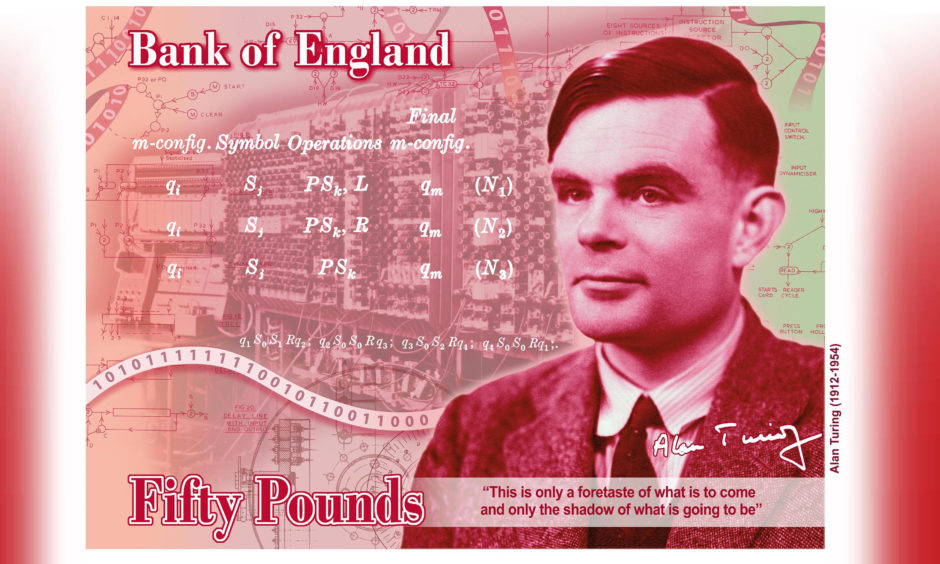

When the Bank of England announced recently that computer pioneer and codebreaker Alan Turing will feature on the new design of it’s £50 note, it was a celebration of his code-cracking work that proved vital to the Allies in the Second World War and an acknowledgement of his pardon following conviction under contemporary anti-homosexual laws in 1952.

The £50 note will be the last of the Bank of England collection to switch from paper to polymer when it enters circulation by the end of 2021.

But as the Bank of England marks it’s 325th anniversary on Saturday June 27, does cash have a future at all?

According to Sarah John, who is Chief Cashier at the Bank of England, there’s no doubt that cash is in decline.

In 2007 cash accounted for 61% of total transactions and by 2017 this had reduced to just 34%.

In 2017 debit cards became the most frequently used payment method, taking over from cash for the first time, with industry forecasts predicting that cash will account for just 16% of total payments by 2027.

But while the Chief Cashier admits she doesn’t have a crystal ball to see what’s going to happen to cash over the next decade, the future won’t be cashless, she claimed, with just over a third of payments (13 billion) in the UK still made in cash, 1.3 million people still without a bank account and 2.2 million people – or 4% of the population – relying predominantly on cash for everyday spending.

“How fast cash use actually declines in the UK will depend on a wide range of factors, including technological developments, consumer preferences and government policy,” she said.

“For example, in some countries, like Sweden and China, new peer-to-peer payment offerings have come to market that allow people to make small payments via messaging apps.

“The introduction of this technology appears to have contributed to the decline in cash usage.

“We therefore need to prepare for a world with less cash usage, without knowing exactly what path cash will follow, and be prepared to respond effectively and sensitively as society’s payment preferences change over the next few years.

“But beyond that, there are also significant numbers of people who want to choose to use cash. There’s a variety of reasons why people choose cash, including because it is a useful budgeting tool, it is quick, and it works when other payment methods do not.

“I therefore expect that cash will remain a critical part of the payments landscape for some time to come.”

It was Scottish trader Sir William Paterson – who later backed Scotland’s ill-fated Darien scheme to set up a colony in Central America – who first proposed the idea of the Bank of England – the second-oldest central bank in the world.

In 1694, Charles Montagu, Earl of Halifax, adopted his idea, founded the bank and was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer.

The Bank of England began as a private bank that would act as a banker to the government.

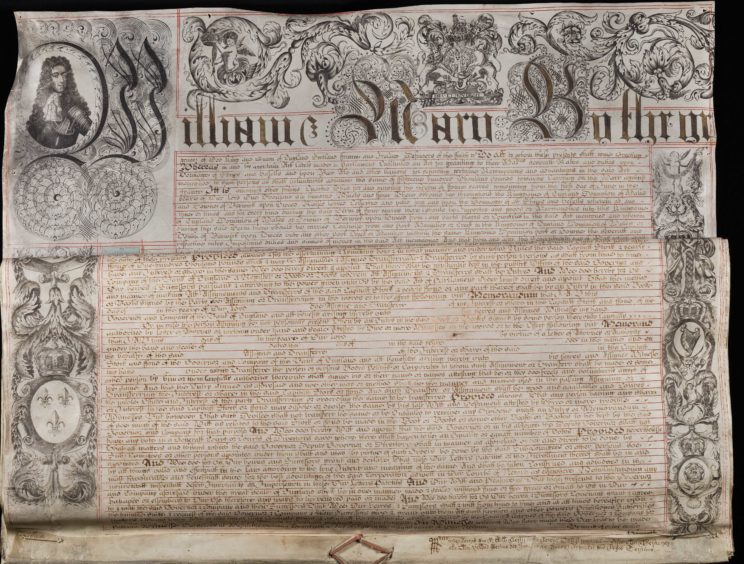

It was primarily founded to fund the war effort against France. The King and Queen of the time, William and Mary, were two of the original stockholders.

The original Royal Charter of 1694, signed by King William III, explained that the bank was founded to ‘promote the public Good and Benefit of our People’ – a sentiment still enshrined in today’s mission statement which says: ‘Promoting the good of the people of the United Kingdom by maintaining monetary and financial stability’.

Milestones in the 325 years since have included the ‘South Sea Bubble’ financial crash of 1720, the first denominated banknotes issued in 1725, the move to London’s Threadneedle Street in 1734 where the bank still stands today, the first branches opening in 1826, the first official employment of women in 1894, Nazi counterfeit note attempts during the Second World War, Queen Elizabeth II becoming the first monarch to appear on Bank of England banknotes in 1960, the UK’s crash out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992 and the release of the first polymer banknote – the £5 featuring Sir Winston Churchill – in 2016.

But there are plenty challenges on the horizon too. Looking to the future, the Bank of England recently warned that a ‘no-deal’ Brexit could trigger a material shock to the UK economy while causing widespread disruption for EU companies by cutting them off from London-based banks.

Stating that the risk of Britain crashing out without a deal had risen, the bank said the City of London was ready to withstand such a scenario and avoid banks failing, as they did in the 2008 financial crisis. However, there would still be major disruption for companies.

Beyond that, the bank’s governor Mark Carney has also stated that a ‘new finance’ is required to adapt to a new economy driven by changes in technology, demographics and the environment.

These priorities would ensure the bank can enable the new economy; ensure the resilience of the financial system; and support the UK’s transition to a carbon-neutral economy.