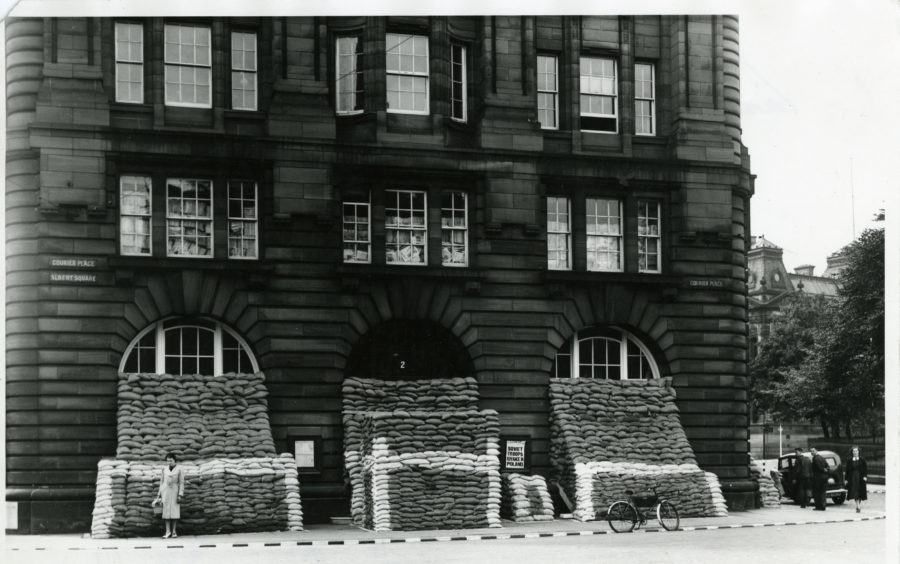

Eighty years after Britain declared war on Nazi Germany and entered the Second World War, Michael Alexander delves into The Courier archives to see how the build up to war was being reported and how, even before hostilities began, ordinary peoples’ lives were being affected.

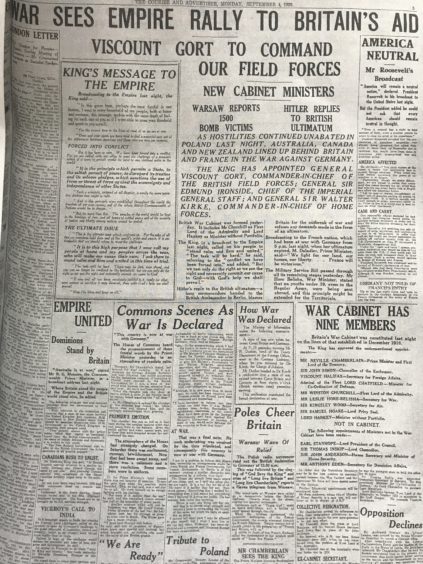

When Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain stood up in the House of Commons 80 years ago on September 3, 1939, and declared those fateful words ‘This country is now at war with Germany’, it was met with an atmosphere of “resolute calm” by MPs, according to The Courier’s report of Monday September 4, 1939.

Under the headline ‘War Sees Empire Rally to Britain’s Aid’, the page five report told how in response to Britain’s demands for the “immediate cessation” of hostilities by Germany in Poland, Hitler “blames Britain for the outbreak of war and refuses any demands made in the form of an ultimatum”.

In the end, it was a further six weeks before the first German air raid on Britain – the Battle of the River Forth when RAF Spitfires fought 12 Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 88 bombers attacking Rosyth naval base on October 16.

But with The Courier describing Hitler’s government as “gangsterism masquerading as statesmanship” and criticising the Fuhrer’s “criminally-minded trickery”, the build up to war at home had been evident in Courier Country and beyond for some time.

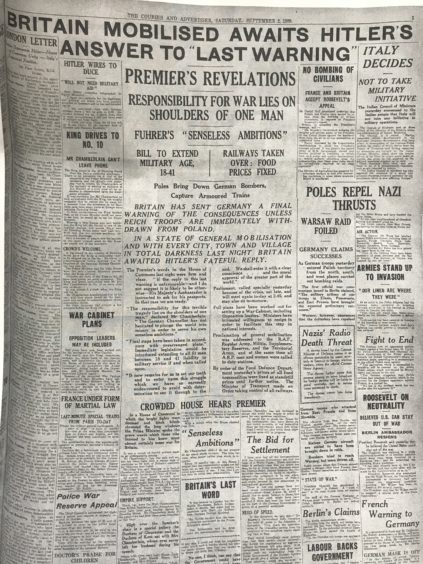

On September 1, 1939 – the day that Nazi Germany invaded Poland – The Courier told how three million mothers and children were scheduled for “precautionary evacuation” from Britain’s cities that day to the coast and countryside.

“The Ministry of Health stresses that it is a precautionary measure and does not mean that war is regarded as inevitable,” the report said.

“In Scotland it is estimated that about 250,000 persons, principally children, will have to be provided for.

“In Dundee, the education offices below the Caird Hall had been turned into a food-packinghouse as the staff of Mr John R. Cameron, evacuation officer, prepared for the evacuation of children.

“Under the scheme children are supposed to carry a day rations, but in case any parents are not able to afford food for the journey, the authorities are providing it.”

When the evacuation was announced, Mr Cameron’s staff, whose normal duties were clerking and secretarial “got down to it” and started the job of packing food into bags for the children.

“By six o’clock typewriters and filing cabinets had disappeared – their place there stood tables piled high with tins of milk, biscuits and “bully” beef and chocolate,” the report said.

There was still urgent need for blankets and, certain schools, helpers, The Courier reported at the time.

Subsequent reports told how the first day of evacuations went “without a hitch”. Observers were struck by the “calmness” of the Dundee children who carried their kit and wore their gas masks strung around their necks.

Meanwhile, in Fife, arrangements for the reception of evacuees were “practically complete”.

Approximately 4000 children, mothers, teachers, helpers and priority classes were being sent to the Cupar area. They would arrive from Edinburgh in four trains on September 2.

“In Cupar, burgh officials have been asked to supply accommodation for 1900 of whom about 800 were unaccompanied children,” The Courier said.

“Castlehill School will be the Cupar assembly point after the arrival of the children, and those who are to be taken to live in the landward area will be conveyed in buses to the schools and public halls in the areas, and from there distributed among the households where they are to have their temporary homes.”

Under the headline ‘Aberfeldy ready’, the first contingent of evacuated children arrived by special train at Aberfeldy on September 1 with more expected in the days that followed.

In Arbroath, 1871 children were expected from Dundee, and in the landward area, 1053.

“The children will be met by billeting officers and conducted to the high school,” the report said.

“Three trains will arrive at Montrose from shortly after three o’clock onwards, and tomorrow another four are due.

In St Andrews over 1800 children from Edinburgh arrived at the Burgh School and Madras College “where young children will be given a glass of milk, adults a cup of soup or tea, and school children a cup of cocoa. Each person will also receive two biscuits.

Proceedings didn’t always go according to plan, however.

On September 2, The Courier told how a train carrying evacuee children from Dundee to Fife was involved in an “alarming incident” at Leuchars Junction.

A luggage truck slipped off the platform onto the tracks shortly before a train carrying evacuee children was due to pass through.

“The train, travelling at about 40 mph, sent the wrecked truck catapulting along the platform for a distance of 30 yards,” the report said.

“Fortunately it struck nobody. The luggage contained a basket of carrier pigeons whose bodies were strewn along the line for more than 100 yards. Members of the station staff quickly disposed of birds which were not quite dead.

“Two or three suitcases were knocked to smithereens, and shirts, collars, coat hangers, boots, golf balls, & c, littered the permanent way.

The train drew up just beyond the station, but proceeded on its way after it had been ascertained that there was no damage to rolling stock.”

Then, on September 5, beneath a report on the torpedoed Athenia and a page of war weddings, a report detailed how a meeting of Angus County Council raised concerned about the “dirty condition” of Dundee children arriving in Angus.

“It was not fair to other people that they should have children coming into their homes infecting and contaminating them,” the report said.

At first, the football card was unaffected. ‘Football as usual’ was the headline on September 2.

However, by September 4, the official news was being reported that there would be “no football under further notice”.

The realities of what would be a six year war costing 85 million lives were only beginning to bite.