It is one of the most memorable scenes in cinema history.

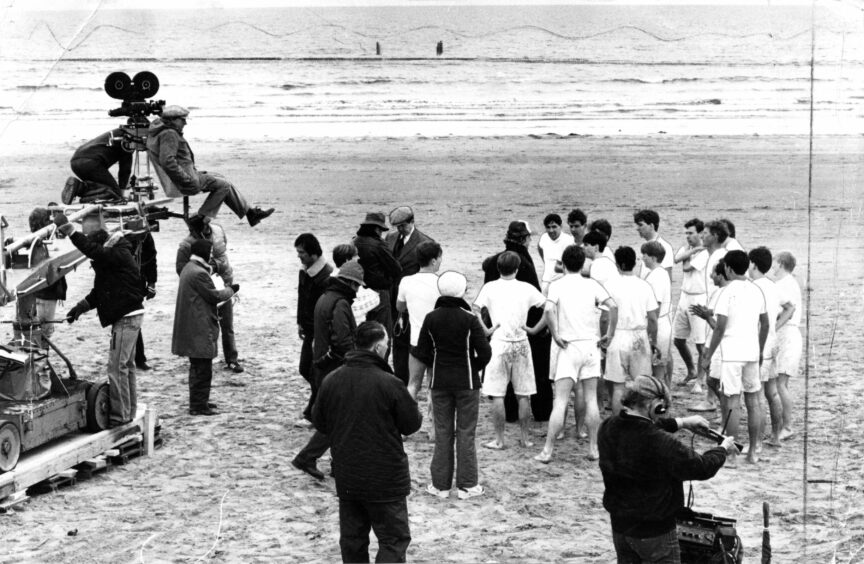

The famous slow-motion beach run from Chariots of Fire on the West Sands in St Andrews was filmed exactly 40 years ago on April 24 1980.

Featuring a parade of young men jogging through sand and surf, the sequence has made composer Vangelis’ piano-and-synth piece almost synonymous with the act of running.

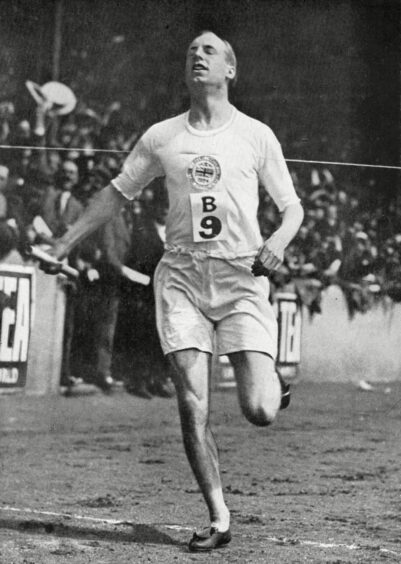

Chariots Of Fire told the story of Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams, who both won gold medals for Britain at the 1924 Paris Olympics.

It highlighted the Christian stance of Eric Liddell never to run on a Sunday and the anti-Semitism Abrahams had to endure during his life.

Liddell was a Scottish rugby international and sprinter who was dubbed “The Flying Scotsman” while at Oxford University.

He was all set for a showdown with Cambridge University’s Abrahams in the 100 metres until the discovery that the qualifying heats for the events would take place on a Sunday.

The new moderator of the Church of Scotland’s general assembly, Arbroath’s Rev Dr Martin Fair, said he loved the film and was a big fan of Liddell.

“I’m always inspired by people who stand on their principles – whether agreeing with them or not,” said Mr Fair.

“There aren’t many out there like Liddell who would put personal fame and fortune aside to do the right thing.

“As a Christian, I’m challenged daily to live as he did.”

St Andrews was chosen because it resembled Broadstairs, where Liddell did most of his training.

The auditions were held at the Royal and Ancient Golf Club in St Andrews and in Leven.

Hamilton Hall, a fine redstone student resident hall, overlooking the last green on the Old Course, was transformed into the Carlton Hotel.

The Carlton was used for outside scenes but Russack’s Hotel was used for interior scenes.

Training scenes were filmed on the West Sands and 1920s cars were brought in by the film makers to give background authenticity.

Despite the gorgeous backdrop the weather conditions were chilly.

After the run, the extras had lunch with the actors.

The film unit eventually moved to Crieff to shoot a Highland Gathering scene.

There are many connections locally to Chariots Of Fire including Dundee heavy games athlete Grant Anderson taking part in the Highland Games scene.

The church service in the following scene was shot at Amulree Church of Scotland.

VisitScotland has already acknowledged St Andrews is synonymous with Chariots of Fire, with the sequences on the West Sands beach now part of film legend.

However the filming at the time did anger some St Andrews residents.

Councillor Anthony Jackson told a meeting of Fife Regional Council that residents did not appreciate road closures for the “frivolous reason” of a company filming.

Councillor Robert Gough, convener, said the film company needed certain areas closed to modern traffic for their production on the great rivalry between Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams.

He said the filming operations were brief and traffic was not held up for more than 10 minutes at any one time.

He said the decision to let the film company go ahead was taken by the administration and “this was perfectly correct”.

A plaque was also put in place at West Sands to celebrate the filming of the Academy Award-winning movie Chariots of Fire.

The plaque was donated by Cinema 100 to celebrate the centenary of world cinema in 1996. It was received by the then Kingdom of Fife Tourist Board and passed on to Fife Council.

They finally put it up on a specially-sculpted grey sandstone plinth at the town’s Bruce Embankment, overlooking the beach, in November 1997.

The beach was also featured on a ”movie map” which encouraged film fans to visit 186 iconic film and TV locations across the UK.

The iconic scene was recreated in 2012 on the West Sands as the Olympic torch embarked on the second of a two-day journey through Fife (pictured above).

The honour of holding the torch went to 13-year-old athlete Joseph Forrester, who led a group of 20 pupils from Madras College in emulating one of cinema’s most famous scenes.

A new edition of the film was also made available to every school in the country for every schoolchild to learn about the achievements of “perhaps the most celebrated Scottish Olympian of all time”.

Chariots of Fire plot

The movie tells how Liddell was boarding a boat to the 1924 Paris Olympics when he discovered that the qualifying heats for his event, the 100-metre sprint, were scheduled for a Sunday.

A devout Christian, he refused to run on the Sabbath and was at the last minute switched to the 400 metres.

In truth, Liddell had known the schedule for months and had decided not to compete in the 100 metres, the 4×100-metre relay, or the 4×400-metre relay because they all required running on a Sunday.

The press called his decision unpatriotic, but Liddell devoted his training to the 200 metres and the 400 metres, races that would not require him to break the Sabbath.

He won a bronze medal in the 200 and won the 400 in a world-record time.

In the 200m he finished in front of Abrahams who had won gold in the 100m Liddell missed.

A crippling Paris heatwave didn’t help his tactics for the 400m.

Liddell said: “I run the first 200m as hard as I can.

“Then, with God’s help, I run harder.”

As he went to the blocks, an American team masseur slipped him a piece of paper with a Biblical quotation: “Those who honour me, I will honour.”

Liddell kept the message in his palm as he sprinted clear of American Horatio Fitch, who’d broken the world record in the semi-final.

As Fitch closed, Liddell threw his head back, opened his mouth, flailed his arms and won by six metres.

Once he took part in a meet knowing the race started 30 minutes before a ferry he had to catch.

A taxi was laid on with the engine running.

The plan was that Liddell would run the race, jump in the taxi and make the ferry.

After winning, Liddell kept going, waving as he ran to the car park.

But then the band struck up God Save The King.

Despite his hurry, courteous Liddell came to attention and stood counting the seconds.

Finally they stopped and he could set off again. But second place had gone to a Frenchman, so the band played La Marseillaise.

Liddell stopped and stood to attention once again.

He finally made the ferry, but only by leaping from the harbour as the boat pulled away.

Life after running

Liddell soon returned to China, where he had been born, to continue his family’s missionary work.

He died there in 1945 in a Japanese internment camp.

Under a prisoner-exchange deal he could have left the camp, but gave this up so a pregnant woman could go in his place.

Abrahams won the 100m, the last Brit to do so until Alan Wells took gold at the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

Abrahams suffered an injury in 1925 that ended his athletic career.

He later became an attorney, writer, radio broadcaster, and sports administrator, serving as chairman of the British Amateur Athletics Board from 1968 until shortly before his death in 1978.

Roger Ebert Chariots of Fire review

Award-winning American film critic Roger Ebert told how he was “so deeply moved” by the movie when it came out in 1981.

Mr Ebert was a film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013.

In 1975, he became the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism.

His review stated: “This is strange. I have no interest in running and am not a partisan in the British class system.

“Then why should I have been so deeply moved by “Chariots of Fire,” a British film that has running and class as its subjects?

“I’ve toyed with that question since I first saw this remarkable film in May 1981 at the Cannes Film Festival, and I believe the answer is rather simple: Like many great films, “Chariots of Fire” takes its nominal subjects as occasions for much larger statements about human nature.

“This is a movie that has a great many running scenes. It is also a movie about British class distinctions in the years after World War I, years in which the establishment was trying to piece itself back together after the carnage in France. It is about two outsiders, a Scot who is the son of missionaries in China, and a Jew whose father is an immigrant from Lithuania. And it is about how both of them use running as a means of asserting their dignity. But it is about more than them, and a lot of this film’s greatness is hard to put into words. “Chariots of Fire” creates deep feelings among many members of its audiences, and it does that not so much with its story or even its characters as with particular moments that are very sharply seen and heard.

“Seen, in photography that pays grave attention to the precise look of a human face during stress, pain, defeat, victory, and joy. Heard, in one of the most remarkable sound tracks of any film in a long time, with music by the Greek composer Vangelis Papathanassiou. His compositions for “Chariots of Fire” are as evocative, and as suited to the material, as the different but also perfectly matched scores of such films as “The Third Man” and “Zorba the Greek.” The music establishes the tone for the movie, which is one of nostalgia for a time when two young and naturally gifted British athletes ran fast enough to bring home medals from the 1924 Paris Olympics.

“The nostalgia is an important aspect of the film, which opens with a 1979 memorial service for one of the men, Harold Abrahams, and then flashes back sixty years to his first day at Cambridge University. We are soon introduced to the film’s other central character, the Scotsman Eric Liddell. The film’s underlying point of view is a poignant one: These men were once young and fast and strong, and they won glory on the sports field, but now they are dead and we see them as figures from long ago.”