The days of waxworks and strongmen gave Dundee a glimpse into the world of the macabre.

Monarchs stood shoulder-to-shoulder with murderers in the waxwork show where admission was a penny at the Overgate.

Flair and showmanship

Another attraction was gentlemen who dined publicly on broken glass and candles which were washed down with draughts of paraffin.

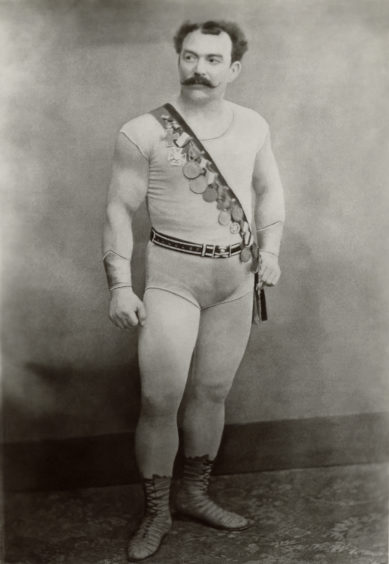

Strongmen, ventriloquists, conjurers, palmists, the Human Spider, a pig-faced lady and the laughing mirrors also brought the flair and showmanship of the fairground to Dundee.

There was also the Flying Lady who was wafted off the stage after being hypnotised and floated around in mid-air without visible means of support.

The waxworks and morbid curiosities were a never-failing source of delight to the rising generation including John Miln whose stories of his school days in the early 1900s were discovered again by his son Kenneth.

He said the stories took him back in time to his father’s “vibrant early life in Dundee”.

His late father had some of his stories published in newspapers in Dundee and India where he worked in the jute trade.

In one story he told how the Overgate waxwork show was more or less permanent but each week a new attraction was advertised on the bills in the windows flanking the entrances.

Murder most foul

“The situation of this exhibition was in one of the narrowest and noisiest parts of the street, a few doors east of Birrell’s shoe shop,” he wrote.

“Though the effigies included famous and worthy people, the infamous predominated.

“On entering we were greeted by John Lee, the Babbicombe murderer.

“He was the first in a row which included Neil Cream, Doctor Pritchard, William Burke and Hawley Harvey Crippen.

“Others present were Madeleine Smith, Mrs Maybrick and the principal character in a celebrated Angus murder, the Wife O’ Denside.

“There was a peculiar family resemblance about them, doubtless due to the fixed and glassy stares with which they regarded the audience.”

He wrote that on the first floor there was a tableau representing the murder of King James I at Perth in 1437 whose body was found in a stinking sewer below the monastery.

“On the landing of the stairs leading to the second floor were penny-in-the-slot peep-show machines, depicting execution methods in Britain, France and China,” he said.

“On the second floor was a dais or stage on which the ‘star turn’ appeared.

“Here I have watched the most life-like and entrancing marionette shows I have ever seen.

“Another attraction was the Human Spider.

“This consisted of a lady’s head which materialised in the centre of a mock spider’s body.

“The lady winked and told us the strange story of her life – but I knew the head was made to appear there by a trick involving light and reflections on a slanted piece of glass.

“So I was a disappointed spectator.”

The Man They Couldn’t Hang

An unusual performer was a glass blower and weaver who made beautiful galleons, ornaments and animals out of coloured glass.

Outstanding amongst the ‘amazing attractions’ was also the ‘Man They Couldn’t Hang’.

Mr Miln recalled: “As a warming up exercise he wrapped a clothes-line round his upper body and held it tight. Then he expanded his chest and the rope snapped.

“For the highlight of his performance he twisted another rope round his neck and persuaded five men to hold each end and pull.

“He urged them to do so slowly and steadily while he held a gully-knife ready in one hand to cut the rope ‘in case of accidents’.

“But again the rope broke and he was unscathed.”

He wrote that he saw him many times including once at Greenmarket which he described as the place for free shows.

Big potato

One performer he saw there threw a cannonball high up in the air and caught it in a leather bucket which was strapped to his forehead.

He also threw up a big potato and let it smash into fragments on his brow.

Born in 1900 in Dundee, Mr Miln was educated at Stobswell Primary and Morgan Academy.

He trained with the army in Stirling, Edinburgh and Aldershot, which was followed by a year spent in Egypt.

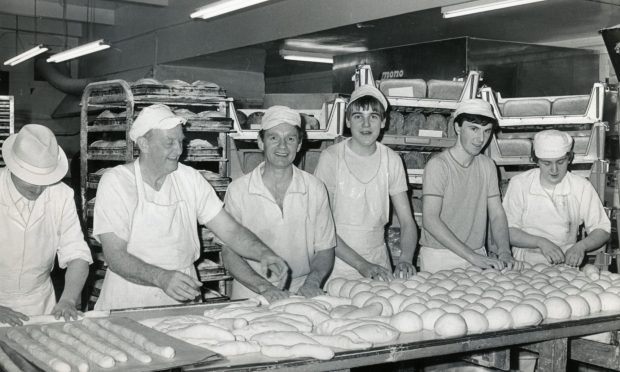

On his return to Dundee, he worked as a spinning department overseer at a Dundee jute mill before signing on for overseas service at Megna Jute Mills, West Bengal, India, where he remained for 33 years.

He married Elisabeth (Betty) in 1928 who lived in India for some 26 years.

The couple eventually retired from India in 1956 and settled back in Broughty Ferry, where they lived for the remainder of their lives.

During his time in India he became very interested in Tibet and Tibetan culture.

He got to know David MacDonald the eminent author who spent two decades in Tibet as the British Trade Agent.

Mr Miln frequently visited him at his home in Kalimpong near Darjeeling and became fluent in Hindi, Bengali and was good at spoken French.

Stalwart gentleman

While in India he wrote many articles for the Calcutta Statesman newspaper and during his retirement he was a regular contributor to the Courier and Evening Telegraph.

A very well read man, he was always with a copy of the complete works of William Shakespeare at hand.

He died in 1979.

Son Kenneth said: “My late father was one of those stalwart gentlemen who, through mainly their own efforts, made a success of their careers while still giving good quality time to family life.

“He was always ready to chat and could talk to, and with, anyone at any time – a rare ability.

“I am very proud of my ‘old man’.

“Indeed, he was a better man than I.

“My late father’s stories of his school days in Dundee serves to remind me of his very interesting and vibrant early life in his native Dundee.”

Long history of death and wax

The link between wax images and death has a very long history.

The Romans made a public display in their homes of wax effigies of long departed ancestors.

Other cultures also commemorated the dead using effigies, sometimes using clay instead of wax.

The museum of Westminster Abbey in London has a collection of British royal wax effigies going back to that of Edward III of England who died in 1377.

Madame Tussaud

Philippe Curtius, waxwork modeller to the French court, opened his Cabinet de Cire as a tourist attraction in Paris in 1770, which remained open until 1802.

He bequeathed his collection to his protege Marie Tussaud, who during the French Revolution made death masks of the executed royals.

In 1835 Madame Tussaud established her first permanent exhibition in London’s Baker Street.

By the late 19th century most large cities had some kind of commercial wax museum, like the Musée Grévin in Paris or the Panoptikum Hamburg, and for a century these remained highly popular.

Waxwork exhibitions were equally as popular in the United States and could be found both in amusement parks such as Coney Island and in dime museums.

New York rival

One of the most famous was the Eden Musee in New York, which presented waxworks displays to rival that of Tussaud’s in London.

Exhibitions which emphasised aspects of the naked body, also featured on fairgrounds, penny gaffs and side shows in the Victorian era.

In line with other types of shows such as the fat lady and tattooed women, the emphasis was on the display and exhibition of the body under the guise of the living statue.