It’s 65 years since passenger trains were withdrawn from the Dundee and Newtyle Railway. Gayle Ritchie looks at what happened to one of Scotland’s earliest railways

Turn back to the clock to 1830s Dundee and imagine you had never seen a train in action.

It was an exhilarating experience for Sandy Gall, an old Auchmithie fisherman who climbed the Law Hill to see the first locomotive on the newly created Dundee and Newtyle Railway line chugging off into the distance.

“It’s a humbug, a perfect humbug,” he declared.

“It puffed an’ it puffed, it cam’ an’ it cam’, and when it saw me it ran into a hole i’ the hull an’ hoded itsel!”

The first railway line in Dundee was opened for passengers in 1831 and led up to the slopes of the Law Hill, through a tunnel, across the Sidlaw Hills and on to Newtyle in the rich farming country of Strathmore.

As one of Scotland’s first very railways, it was a primitive effort.

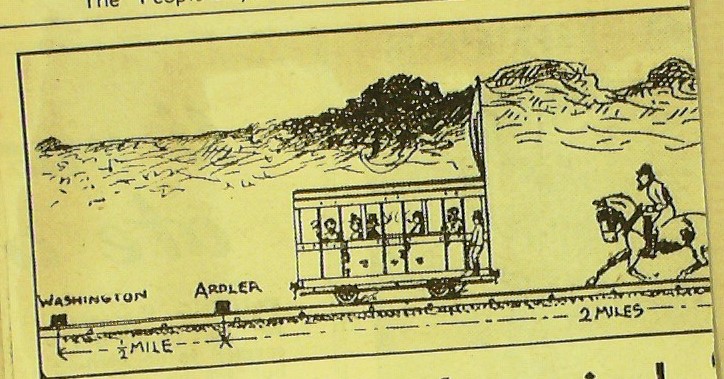

The train initially consisted of stationary engines positioned at three inclines which hauled the carriages uphill by ropes. On level ground, the carriages were drawn by horses.

Charges for a single trip were 1s 6d inside, and outside was 1s.

A concessionary charge of 9d was given to sheep shearers as there was a shortage of them in the Strathmore area.

The authorities issued the following warning: “Although passengers on the outside have a fine view of the countryside, they are in great peril when approaching bridges.”

William Whitelaw, the man in charge of the horse which took up haulage in the railway’s very early days, was an ingenious man.

He made a sail out of a wagon sheet and attached it to a pole on top of the carriage and set it to the favouring breeze. This helped speed things up to around 20mph and lightened the strain on the horse.

The sail helped him along wonderfully, but the locomotive engine made two years after the line was opened took the wind out of Willie’s sails.

First railway in northern Scotland

With the introduction of railways in the first half of the 19th century, small lines had sprung up all over the UK.

Their main purpose was usually the transportation of coal to nearby towns or industrial areas.

The Dundee and Newtyle Railway Company was formed in 1826 and in the following years tenders were invited for engineering works.

It was the first railway to be built in the north of Scotland and the first not to rely on coalfields for the bulk of its traffic.

“The Dundee and Newtyle Railway is one of the oldest railways in Scotland, authorised on the same day as lines in Glasgow and Edinburgh,” says Tayside rail enthusiast John Ruddy.

“However, the generous compensation offered to landowners and the difficulty of building the tunnel through Dundee Law meant it didn’t open until six years later.”

The construction of the railway was complicated by the decision to build a tunnel through Dundee Law, which was finally completed in 1829, allowing the 11-mile line to open to traffic on December 16 1831.

The railway was to offer a faster link between the manufacturing, industrial city of Dundee and the agricultural hinterland of Strathmore, having deduced that using horse and cart to deliver goods by road took too long.

The city was rapidly expanding with jute mills on the rise and rail was a cost-effective way of getting goods like coal and lime in to Strathmore and agricultural produce back out.

However, passengers soon provided the majority of the income.

The line terminated at Newtyle which, at that time, was little more than a mill and a few houses, unlike Forfar or larger Strathmore towns.

It was built with a 4 feet 6½ inches gauge, there being no accepted standard gauge at that time — and this led to problems connecting it with later lines coming in from Perth and Arbroath, which were different sizes.

An extract from The Courier at the time stated: “The Railway betwixt this town and Newtyle has at length been opened. On Friday last (16th) carriages started for the first time for the conveyance of goods and passengers. The distance from Newtyle to the temporary place of starting (it would later move from Dundee’s Ward Road to the harbour) is nearly 11 miles, and was gone over in about an hour-and-a-quarter, conveying along with it about 40 passengers.”

Up and over

The railway had several unusual features in its journey across the considerable heights of the Sidlaw hills.

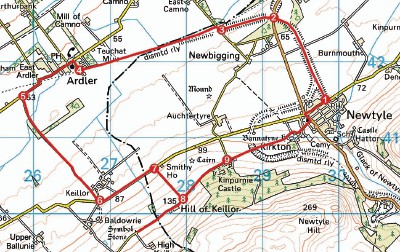

Rather than going round them, engineer Charles Landale decided on a policy of “up and over”, and this resulted in three inclines, at the Law, Balbeuchly and Hatton.

The inclines were worked by stationary steam engines while coaches and wagons were pulled by horses over level stretches of line.

Later, steam locomotives – the first in Scotland – were used although horses provided back-up if they broke down.

Wheezing and spluttering

In September 1833, two steam locomotives, the Earl of Airlie and Lord Wharncliffe, replaced the horses and made their first trip on the line.

Built in Dundee by James and George Carmichael, the locomotives were the first to run in Scotland. The brothers became widely known for their genius as engineers and helped to cement Dundee’s reputation as an engineering centre.

The first engine to run was the Earl of Airlie although it got off to a bad start. To test the engine’s powers, 20 wagons, each laden with six tonnes of coal, were lined up.

There were cheers when the long train moved off with relative ease but then it wheezed and spluttered and came to a dead stop. The load was reduced allowing it to steam triumphantly out of sight.

There were cheers when the long train moved off with relative ease but then it wheezed and spluttered and came to a dead stop.”

In 1834, a third locomotive was acquired, the Trotter.

Its derailment at Pitpointie on June 15 1834, resulted in the death of John Anderson, the miller at Auchterhouse.

Two years later, in 1836, a fourth engine known as John Bull from the great locomotive works of Robert Stephenson & Co, was bought.

Three or four passenger trains ran each way daily, according to season. Goods transported included cinders, hay, iron, flax, coal, lime, potatoes, grain, manure, stone and slate as well as ale, silks and gold plate.

Standard gauge was adopted in 1849 and during the 1860s deviation lines were opened to avoid the three inclines which fell into disuse.

The station at Ward Street in Dundee, where the British Telecom building now stands, was closed.

The line was absorbed by the Scottish Central Railway Company in 1863, which in turn was taken over by the giant Caledonian Railway Company in 1865.

The line was extended in 1861 from Newtyle to Meigle to join the Scottish Central Railway running from Perth through Coupar Angus and Forfar to Aberdeen.

Branch lines connected Alyth (from Meigle at the Alyth Junction) and Blairgowrie (from Coupar Angus).

This train transported soft fruit grown locally to Covent Garden in London.

Smoking on trains – “almost insufferable”

Remember the days when people could smoke on public transport? Even in 1832 it cause some offence on the Dundee and Newtyle Railway route!

A note sent to The Courier in June 1981 from Christopher Dingwall of Dundee Museums and Art Galleries tackled the subject of smoking and included an extract from a letter written by a cousin of the Kinloch family who had been travelling on the line, on her way to Kinloch House in 1832.

She wrote: “After passing through the tunnel, a dandy waved his hand indicating his intention to take a seat – in his hand a fishing rod and in his cheek a cigar. He tripped lightly to his seat, and though snug himself, annoyed me with the fumes of his tobacco.

“A labourer sat behind him with a cutty-pipe stuffed with pig-tail. The smoke and smell was almost insufferable, and I was almost choked.”

Petticoats

These days, boarding a train is fairly easy (unless it’s packed), and unlikely to compromise a lady’s dignity. But back in the 1830s, it was a different story, as Iain Buick notes in his book, Newtyle Through The Ages.

In it, he quotes from a letter penned by one of the first passengers on May 28 1832 to her cousin: “You can’t think how delighted I was last week with the ride from Dundee to Newtyle on the Railway Coach. The bustle at taking my seat. By the by, neat ladders should be furnished by which to ascend the coach instead of compelling the ladies to scramble by long strides, and coming off the coach is worse for one’s petticoats are entangled and the inconvenience is so bad as you can’t imagine.”

Snowed in

During the Great Freeze of winter 1947, a passenger train was snowed in for over a week near Auchterhouse.

In his book, The Dundee and Newtyle Railway, Niall Ferguson recalled: “Passengers made their way to the village where they were put up in various houses including Auchterhouse Smiddy, where five schoolboys on their way home from Dundee spent the night before finishing their journey home to Newtyle on foot through the snow.”

Accidents

Accidents were common on the line as the trains were pulled up the inclines by a rope just 2.5 inches in diameter.

On one occasion, the train was descending the slopes of the Law towards the city when the rope frayed and broke, causing the carriage to rush downhill at great speed.

It dashed into the station on Ward Road and was brought to a standstill at such force that passengers were said to have been “thrown” onto the platform.

“Compensation for these accidents was just one additional expense which meant that the original shareholders never received a dividend until 1844,” says John Ruddy.

Tragedies

In September 1833, William Carr was killed by a runaway train on the Hatton incline and the railway company paid £1 3s 6d for a coffin.

Isobella Simpson and her daughter were killed on the Law incline by a runaway train in September 1835 and the railway company paid £7 10s funeral expenses.

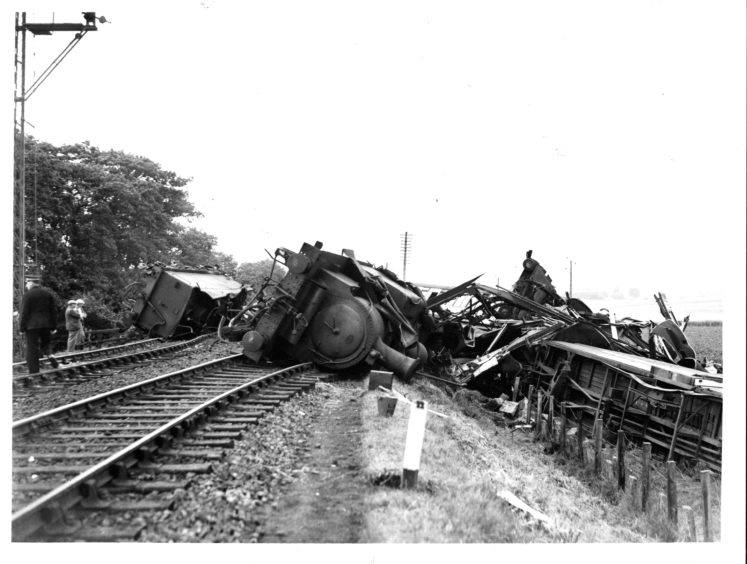

On July 17 1948, the Crewe-built Swiftsure was hauling the Aberdeen to Glasgow express, four postal sorting vans and seven passenger coaches.

As it thundered past Meigle towards Ardler Junction, where two lines gradually converged, the crew were unaware that the smaller and slower Dundee to Newtyle train was approaching the same stretch of track, also west bound.

For it to have been allowed onto the main line was a catastrophic error.

As the two trains came together, the 321-ton express smashed into the trundling tank engine.

The Swiftsure was spun like a toy and its coaches piled headlong into fields. The first few carriages, unmanned, were reduced to splintered wood and twisted steel. The Dundee tank engine was launched along the tracks and landed with its wheels in the air.

Express driver David Nutt had been thrown clear and went searching for his crew-mate – but fireman James Smith was trapped beneath the tender and grievously injured. He died in Dundee Royal Infirmary that night.

Meanwhile, in the cab of the tank engine, fireman Robert Nixon lay stricken with a smashed leg and driver John Laing had been hurled against the controls. He, too, died later in Dundee Royal Infirmary while Nixon lost his leg.

Death knell

Following damage caused by the Second World War, in 1948 the UK’s railways were nationalised, and the line became part of British Railways.

As motor transport developed and roads improved, the need for rail in certain areas decreased.

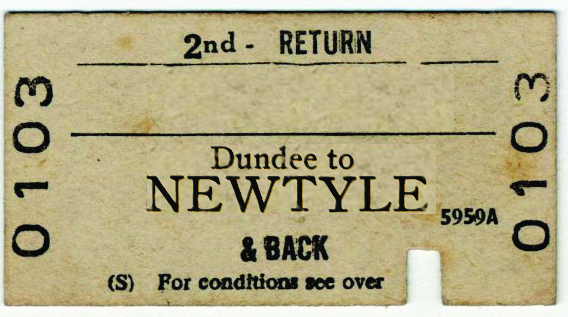

Mobility was changing and by the mid-1950s, the Dundee to Newtyle Railway was no longer economical and passenger services were withdrawn on January 10 1955.

Freight services continued, but the Auchterhouse to Newtyle section closed in 1958, and the remaining route to Dundee ceased operation on April 5 1965.

The yard at Lochee and the goods sidings at Maryfield were finally shut on November 6 1967.

Still standing

“One station that formed part of the Dundee and Newtyle Railway is still standing,” says John Ruddy. “And it is one of the oldest railway buildings in Scotland.

“Originally called ‘Offset at the Back of Law’, a derelict building in the grounds of Kings Cross Hospital is all that remains of this line in Dundee.”

The fate of Newtyle station and railway line

In Newtyle, the old station and a goods shed survives on Commercial Street, and along the lines remain various cuttings, embankments and signal houses.

On March 17 1980, the Press and Journal reported that Angus council officials were keen to restore and preserve Newtyle railway station as a tourist attraction.

It was hoped a collection of railway artefacts could be housed somewhere in the village, perhaps with a shop and cafe attached.

Alas, nothing came of this and it’s not known what happened to the artefacts although suspicions were raised that many were dumped in a skip, deemed to be a load of old junk. However, this has not been confirmed.

For a while in the 80s, the station and goods shed were used by Newtyle Bulb and Farming Company as a store.

In 1981, the company applied to demolish part of the disused station which elicited strong objections from local groups.

An application to transform the building into an office and storage rooms in 2015 was successful, but was never acted upon.

In January this year, railway history buffs celebrated after plans to turn the abandoned station into housing went off-track.

Developers proposed converting the derelict category B former railway buildings in Newtyle into four family homes.

The project stalled after it was criticised by Historic Environment Scotland staff for diminishing “the listed building’s architectural and historic interest”.

However the architect behind the scheme signalled the plans are likely to re-emerge with changes to the design.

Claire Herbert, of Aberdeenshire Council’s archaeology service, said the former railway buildings were among the earliest surviving examples in Scotland and recommended that planners ensure a historic record of the building was made for inclusion in the National Record before any work began.

Path Network

A dedicated local group founded the Newtyle Path Network to take advantage of the abandoned rail tracks.

Much of the line is now seeing a new lease of life as walking and cycling routes – the Newtyle Path Network, Sidlaw Path Network and Dundee’s Green Circular.

The landscape along the routes is packed with historical interest; its hills, burns, cottages and farmsteads, dykes and ditches, woods, factories, monuments, castles, echo the past.

“Many walkers come from far and wide to enjoy exploring Strathmore,” says Newtyle and Eassie community councillor Dudley Treffry.

“There have been two recent developments: pursuing the idea of linking the network to the Sidlaw Path Network by opening up the line of the Newtyle to Dundee Railway where it runs through the Glack of Newtyle, and consideration being given to making a feature of the turntable site at the end of the park.”

The old turntable is currently covered in earth and weeds and most people are unaware of its existence.

“The turntable idea has been around before and it remains to be seen if there is the necessary determination to see such a project to fruition,” adds Dudley.

Evidently, much has changed since the line opened almost two centuries ago, but it hasn’t been entirely abandoned to dereliction.

It seems people care enough about this part of their heritage to want it to continue to play a role in their future.