Around three million Anderson shelters were erected across Britain during the Second World War. Some of the corrugated iron structures survive to this day – with some selling for around £1,000. Gayle Ritchie takes up the story.

With their rusting, corrugated iron panels crudely bolted together, Anderson shelters are regarded by some people as rather ugly edifices.

But, in truth, the tunnel-shaped structures are iconic symbols of Britain’s involvement in the Second World War.

Designed to protect families from bomb blasts, they were dug into back gardens the length and breadth of the country.

More than three million of the “easy-to-build” air raid shelters were produced and many survive to this day, often used as storage sheds in gardens, playhouses for children, or beautifully restored into relaxing spaces.

Others stand forlorn and unloved, rotting to the ground, while it’s thought many are submerged, awaiting discovery.

To some people, they are hot property, with Facebook groups such as “Anderson shelter in your garden” acting as a source of inspiration for those who have either bought or inherited them and wish to transform them into unique spaces.

And even some of the most rusty and dilapidated shelters are being sold for around £1,000…

Domestic battlefield

During the Second World War, Britain’s families found their homes on the front line.

People got used to “going without” and the domestic battlefield was littered with air raid shelters, blackout curtains, ration books, gas masks and stirrup pumps, used to extinguish bombs and fires.

The most widely used home shelter was the Anderson.

Officially called the “sectional steel shelter”, it was universally referred to as “the Anderson”, after Sir John Anderson, the architect of air raid protection before the war and the first wartime Home Secretary.

As the official name implied, the shelter was delivered in sections and had to be erected by householders.

The corrugated-steel arched shelter was partly buried in a hole up to four feet deep, then covered with soil.

It was erected in back gardens, and a standard shelter could accommodate six people.

The soil could be planted with flowers and veg, which often led to local, spirit-lifting “best-planted shelter” competitions.

The shelter was remarkably bomb-proof unless it suffered a direct hit but was cramped, draughty and tended to flood after rain, which made sheltering a chilly, rather miserable experience.

The first shelters issued were in Islington, London, on February 28 1939, but folk in Dundee had to wait until August that year.

The shelters cost £7 but were supplied free of charge to people earning less than £5 a week in danger zones.

Eerie sirens would scream like banshees to give people warning of approaching bombers and, later, sound the “all clear”.

Air raids on Britain began in September 1940. Night after night, cities across the country became targets.

A special space

Fairy lights dangle from the roof and a fire pumps out heat from one end of the brightly painted Anderson shelter on Dundee’s Tullideph Road.

It’s a peaceful and attractive space in which Kevin and Mary Findlay relax with a wee drink of an evening.

The couple inherited the Anderson shelter when they moved into their house in 2015.

Back then, it was a damp, rusty, rather ugly structure which stood forlornly at the bottom of their garden.

Now, painted bright red and boasting a table, chairs and chiminea, it’s a hideaway haven that the couple and their friends and family can enjoy.

“It was a right, filthy mess when we moved in – all tired and rusty,” says Kevin, 59.

“The two wooden ends were rotten and there was broken glass everywhere.

“The shelter had been painted brown decades before and the paint was all peeling off.”

The couple got rid of the wooden ends and saved the bottom of the shelter, which was rusting, by embedding it in concrete and spraying a waterproof layer on it.

Kevin, a health and safety adviser, suspects the shelter was used as a coal shed at one point because the ground, which is made of bricks, was black. After they gave it a good scrub, it came up gleaming.

When the couple first discovered the shelter, they had mixed feelings, but ultimately, they were glad the previous owners hadn’t got rid of it.

“We initially thought it was a bit of an eyesore but understood it was a piece of history and were glad it hadn’t just been dumped,” reflects Kevin.

“Now we’ve done it all up, we love to sit it in with a wee drink in front of the fire.”

Mary, 58, says the shelter is “just perfect” for the Scottish climate.

“We’ve often sat in here with friends and family when it’s night-time or raining and just had a little drink or a coffee.

“It’s very easy to maintain – we just sweep it out now and again.

“If we’d kept it the way it was, with the enclosed sides which were all rotten, it would’ve been a bit of a dark, damp space.

“But we’ve kept the basic structure and we enjoy it. We painted it a nice bright red colour and made it a bit of a feature.”

The couple kept the authenticity of the shelter’s interior – by not painting it at all.

“These shelters each have a stamp and a number inside, so there’s a wee bit of history there,” explains Mary.

“They’re quite rare so we do feel lucky to have one, and it’s no surprise to hear folk are selling them for around £1,000.

“We just hope the next people who have it think of it as well as we do.”

An attractive garden feature

Partially submerged and encased in a stone wall, Jackie McKay’s Anderson shelter is an attractive garden feature.

“We moved here in 2004 and the shelter is pretty much as it was back then,” she says.

“We don’t want to get rid of it – it’s a piece of history. We don’t really use it for much, other than to store a few things, but we plan to tidy it up and do a few repairs over the summer.”

Jackie’s shelter, in Dundee’s Seymour Street, has a wall erected around it which she assumes was put up in 1939 – the same year the house was built.

It works to camouflage and strengthen the shelter, and it’s a lovely feature, with wildflowers and plants taking root in the cracks and crevices.

“We believe the house builder put the shelters in the gardens as part of the policy when building the house,” she says.

“There were other, bigger, communal shelters in the ‘backies’ in Hawkhill where my husband grew up.”

Superb shed

Ashley Keay has an Anderson shelter in her garden in Dundee’s Noran Avenue but it’s a big one – designed to accommodate 12 people.

These structures were produced at a later date, to allow more people to take refuge.

The paint on Ashley’s shelter was flaking off when she moved in in 2013, so she commissioned a mate to give it a makeover.

“My friend sanded it, primed it and painted it green and it instantly looked much better,” says Ashley.

“These days, I use it as my garden shed and to store things like bikes and furniture.”

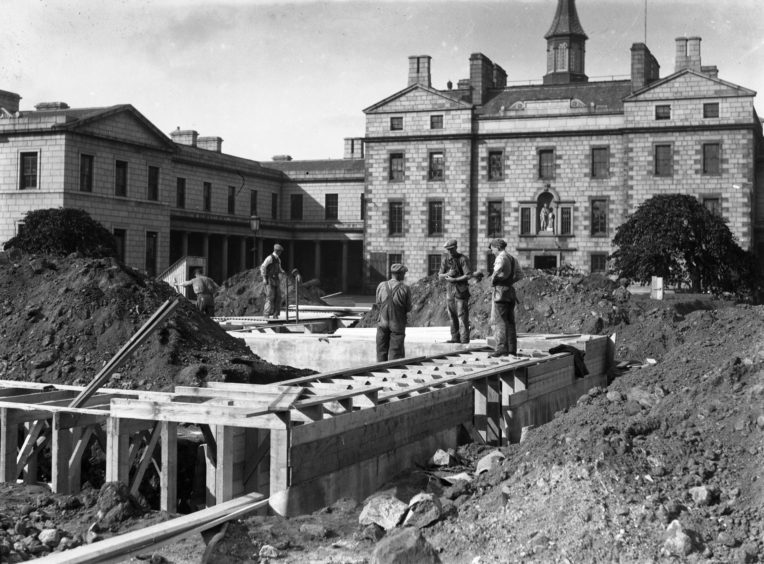

Public air-raid shelters

If people were unlucky enough to be out shopping, visiting relatives, or too far from home to dash into their Anderson shelters when a raid was detected, there were public shelters they could go to.

These ranged from trenches dug in local parks to brick blockhouses on street corners.

In London, at the peak of the Blitz, around 150,000 people were said to have sheltered nightly in underground stations.

For those living in tenements – where there was no garden space – an Anderson shelter was no use.

Building enough air-raid shelters was a huge task for Dundee City Council as it required the full cooperation of the city’s people.

In September 1940, the city engineer identified the basement at 26 Seagate for use as an air-raid shelter.

It would give shelter to people from an adjoining tenement as they had nowhere to go during an air raid.

Despite the urgent need for a shelter, the owner was reported to be: “unwilling to allow his premises to be used for this purpose”.

The proprietor said he felt there was a “great many of these abominations in this neighbourhood”, which were a “waste of money”.

Harsh words, devoid of empathy – and he would have been aware of the air raid 17 days earlier that killed two people at 19 Rosefield Street.

After much delay, the basement was finally requisitioned on January 28 1941.

Morrison air-raid shelters

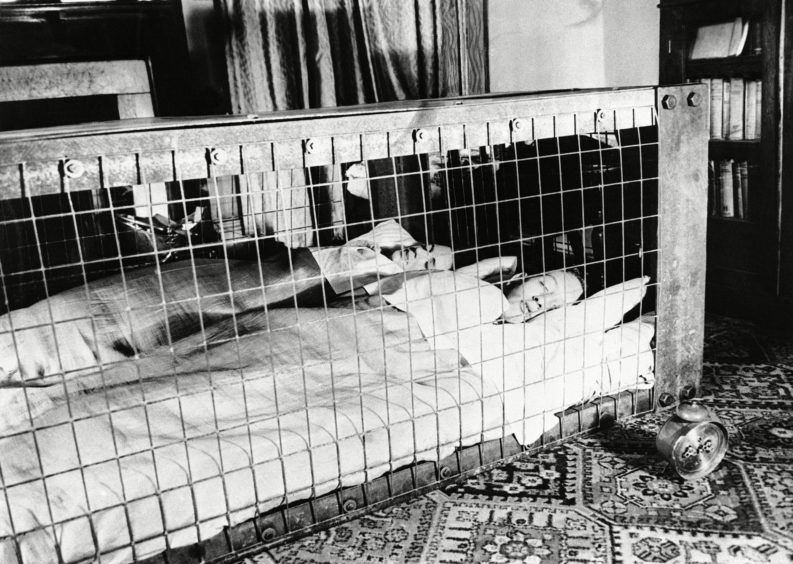

The Morrison “Table” Shelter was introduced in March 1941, for people without gardens.

It was an indoor alternative to the Anderson shelter, which was cold and leaky.

Made from heavy steel, the Morrison was effectively a large metal cage which could also be used as a table. It was named after the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison.

It had a hefty iron frame with a sheet steel ceiling screwed together with chunky nuts and bolts.

Underneath was a crude wire mattress. Like the Andersons, the Morrison shelters were supplied flat-packed for DIY assembly.

But with more than 300 parts, it wasn’t easy.

Around 500,000 Morrison shelters were used by the public.

Physical evidence of wartime Aberdeen

Bleak, gloomy and depressing – apt descriptions of the rectangular, grey edifice in a garden on Aberdeen’s Westburn Road.

Built in 1940, the reinforced concrete air-raid shelter is a rare survivor of the Second World War.

Step inside and you’ll find the original benches, tin plates and cups, and even the stove pipe.

It’s a fantastic resource for those who want to see physical evidence of wartime Aberdeen.

Allan Paterson, an expert on air-raid shelters, enjoys taking groups of school children to visit the building.

“It’s in good condition inside and out,” says Allan, a 68-year-old teacher and the manager of Aberdeen Urban Studies Trust.

“It’s a great place for pupils who are doing projects on the Second World War. Physical evidence is right here in the shelter.”

The shelter, which has two rooms, was built for 24 people – those living in the nine tenement flats of 81 and 83 Westburn Road.

During the Second World War, most tenements in the city had one.

“Staying in the flats during an air raid would have been very dangerous as, especially at the beginning of the war, the pilots often missed their targets,” explains Allan.

“If a 500lb bomb hit the building, it would have been totally destroyed, killing everyone inside.

“The shelter would not have survived a direct hit, but if a bomb landed a bit away, people inside would have been safe from the blast and accompanying shock wave.”

The shelter was listed as a scheduled moment in the 1990s by Historic Scotland. The body deemed it to be an “unusual” survivor, its form “apparently unaltered” since it was erected in 1940.

“The narrow entrance was to lessen the chance of bomb blast getting into the shelter,” explains Allan.

“People using the shelter went round a corner to enter the rooms inside, again, to lessen the chance of bomb blast getting to them.

“The square-shaped holes were for ventilation while the reinforcing material for the structure was metal rods.”

The major targets for bombing in Aberdeen were factories supplying materials for the war effort, the harbour area, ships, the airport, shipbuilding yards, power supplies and military bases.

“When the air-raid siren sounded, people would have made their way to the shelter as soon as they could,” says Allan.

“Many houses in the city were destroyed or badly damaged.”

Lost

On May 8 1945, Germany surrendered, so there was no longer any need for air-raid shelters.

Councils closed all public and communal air raid shelters while demolition followed over the next few years.

If you wanted to keep the shelter, or sell it on as scrap metal, you were charged a nominal fee of £1, around £35 in today’s money.

There were thought to have been 2,031 shelters in back greens and open spaces in Dundee and most of these were probably Anderson shelters. Just how many are left is unknown.

A survey in 1968 revealed there were around 1,700 shelters in Aberdeen.

Two years later, in December 1970, the Press and Journal reported that there was to be “another ‘blitz’ on Aberdeen’s old air-raid shelters, with 150 earmarked for demolition.

It stated: “Since 1968, about 100 have been knocked down, so the demolition of 150 more will leave more than 1,400 of the wartime relics standing.”

Still standing

The survival of Anderson shelters is not only due to their sturdy structure.

Millions of families took refuge in them during the war and told their stories to succeeding generations, keeping them alive in our collective, cultural imagination.

The have become iconic because so many people had, or have, them.

And they are one of the few wartime relics that can still be utilised.

- Do you have an Anderson shelter in your garden? Get in touch at gritchie@dctmedia.co.uk