The Gaiety brought the glamour of the flesh-and-blood theatre to Dundee at the beginning of the 20th century.

The atmosphere of this “new world” was filled with bonhomie, the odour of stale beer, black tobacco, jute mill stoor and fish and chips.

The Gaiety held 1,600 people and the young generation who made for the cheap seats included the late John Miln, whose stories of his school days in the early 1900s were recently rediscovered by his son Kenneth.

In one story, Mr Miln, who died in 1979, told how he spent “many a tuppence” on the “fish supper seats” in the Gaiety in the days around World War One.

“With another tuppence in my pockets a real treat was assured in a bar of chocolate and a bottle of fizz, or, if it was a cold night, a fish supper on the way home,” he wrote.

“There was first however, a process of anticipation and long drawn-out pleasure.

“The bills that decorated the windows of pubs and street hoardings had to be read carefully and full details of the performance digested.

“The more sensational these lurid-coloured posters, the keener was my anticipation.

“Something to chill my marrow was what I wanted.

“Often the name of the play itself was enough – ‘Maria Marten or the Murder in the Red Barn’, ‘The Dumb Man of Manchester’, ‘The Face at the Window’, ‘The Ticket-or-Leave-Man’, ‘Within a Mile O’ Edinburgh Toon’, and ‘Man to Man’.

“I recall the slogan that beckoned me to the last-named play – ‘Along the line the signal ran, there is no play like Man to Man’.

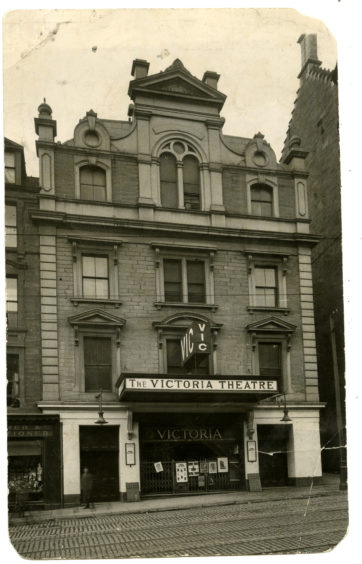

The Victoria Hall was opened in 1876 before it was rebuilt and reopened its doors as the Gaiety Theatre in 1903.

The Gaiety had a luxurious entrance.

From it a cascade of light spilled across Victoria Road and spread its magic from the Wellgate Steps to Cotton Road.

Mr Miln said the foyer was a miniature Crystal Palace and the glittering glass-panelled pay-box housed a fairy which was guarded by “the most flamboyant sentry I have ever seen”.

“He wore a gold peaked cap, gold striped trousers, a military frock coat that scintillated with gold buttons and gold braid and lanyards,” he wrote.

“Into one of his golden epaulettes was tucked a pair of immaculate white gloves.

“As well as guarding the fairy in the pay-box, he paraded in front shouting: ‘Early doors this way! Early doors for pit, stalls and gallery! All seats guaranteed! Early doors now open!’

“While I might stand on the pavement and be thrilled by this splendour, my tuppence did not permit me to enter there.

“The presence too, of the manager Mr Percival – all dignity and authority in his white tie, shirt-front and tails – was enough to deter me.

“So contenting myself with a couple of lungfuls of cigarette smoke and attar-of-roses I wheeled into the alley at the side of the theatre and made for the gallery entrance.

“There sat the cashier, receiving tuppences and pressing a button which flicked a zinc washer, with a hole in the centre, on to the brass slab in front of the tiny window.

“The washer was my passport to wonderland.

“With it in my hand I climbed the umpteen flights of dingy grey stairs that led to the gallery.

“On each landing burned a miserable gas-jet in a bowl-shaped wire cage.

“But, when, ultimately the gallery was reached the effects of the dismal climb soon faded.

“Up there it was warm and cosy.”

Mr Miln, who went to Morgan Academy, said the audience chatted while the orchestra filed into the trench.

“Then, as the house lights dimmed and the footlights went up, the overture began and we fell silent, hushed and expectant,” he wrote.

“As the last notes of ‘Zampa’ or ‘Poet and Peasant’ died away the red velvet curtain rose slowly and we entered a new world.

“Whether it was ‘Svengali’ or ‘The Passing of the Third Floor Back’, whether it was Herbert Mansfield or WAB Kingston with Dora Hammersley, we lapped it up and asked for more.

“The companies usually came for a season. We got to know them and recognise them in the street and (at a later age) to welcome the privilege of standing the hero or villain a quick beer in the interval.

“To have knocked back a pint with Mr Wu (in oriental robes) is something to tell your grandchildren.”

Mr Miln said the Gaiety gallery knew all about audience participation in 1914 as they cheered the hero’s defiant speeches and booed the villain’s threats.

“I remember one play where, after a long suspenseful scene, the hero drank a glass of wine, which everyone on the stage and in the house knew was poisoned,” he said.

“One keyed-up playgoer able to restrain himself no longer shouted into the tragic stillness: ‘Ye stupid ass! Ye’ve pushont yersel!’

“We knew every convention and naturally expected the villain to be black-moustached, sallow, addicted to cigars, and generally dressed in an evening suit.

“The culmination of his crimes took place on the stage bathed in green moonlight.

“I know of no film that had an ending like a live play, where the whole cast took a final curtain.

“Then the hero and heroine to thunderous applause took another final curtain.

“Then finally the hero himself took a final curtain call and thanked us for our attendance and our attention.

“So to the National Anthem followed by the clamber over the steep and hard wooden benches, littered with orange peel, sweetie-pokes, discarded programmes, and empty fizz-bottles, the noisy, clattering rush down flights of stairs and out into the night and reality.”

Mr Miln’s son Kenneth said he found his late father’s collection of memories while moving house after returning from Africa with his wife.

“Having quite forgotten where his papers had been stored for some 50 years, it was indeed thrilling to rediscover my dad’s memories of his boyhood days in old Dundee.

“There are times when I imagine joining my dad during some of his many expeditions to a number of Dundee’s long forgotten yet, at the time, exciting and vibrant places.

“He recorded his experiences with such a degree of clarity and detail that I, and hopefully many others are drawn, albeit in the mind’s eye, into his memories of old Dundee.

“Reading through his tales I can almost feel, taste, hear and taste something of the city’s old and vibrant atmosphere.

“Perhaps it may, some day, be possible through an appropriate medium, to recreate what it was like to live in my dad’s native city.”

The Gaiety continued staging variety and major revues until 1935 when it became a full-time cinema.

Following a relatively minor fire in 1989 the building was found to have suffered severe structural damage and was later demolished.

Conversation