They are two redoubtable old campaigners who have blazed different trails and been made MBEs, but they are now sharing the pages of a new book.

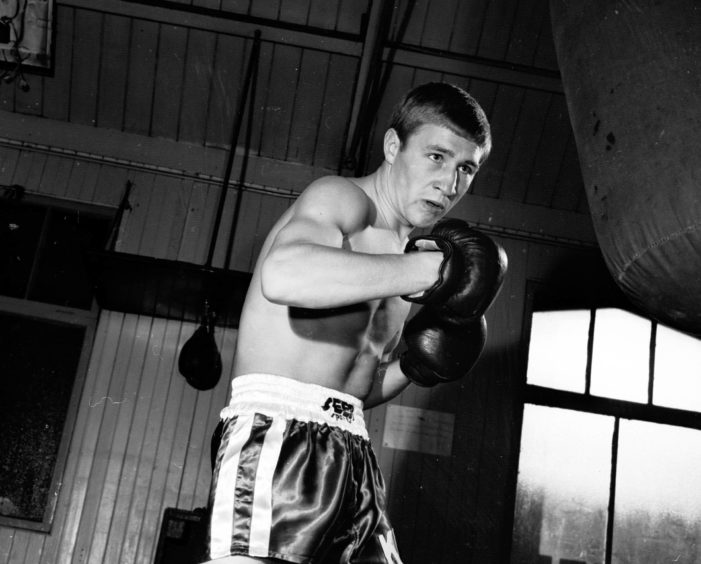

In one corner stands former world champion Ken Buchanan, widely regarded as Scotland’s greatest boxer, whose name features prominently in the sport’s International Hall of Fame.

In the other is Jock Mcinnes, a legendary fundraiser, who has amassed more than £5 million for charity through a remarkable collection of challenges, stretching all the way from Mount Kilimanjaro to the Gobi Desert and countless other places.

The Methil-born Black Watch veteran has written My Pal The Boxing Legend, which details the often beery camaraderie and sweaty comradeship which has developed between these two Scots.

But it also highlights the grievous toll of pain and privation suffered by Buchanan, a man with a million buddies whom he could fit into a phone box; and there is a melancholy climax in the closing pages which reveals how the 75-year-old fistic legend is now fighting dementia in an Edinburgh care home.

The book is a series of rounds – chapters – containing a giddy sequence of short stories with the author enjoying his companionship with Buchanan, even as they grapple with dodgy agents, shadowy backroom figures, the occasional gangster – ‘Mad’ Frankie Fraser makes a brief but pointed appearance – and some of the best boxers in the business.

But, while it is clear that Mr Mcinnes holds his compatriot in the loftiest regard, this is no starry-eyed tale of life with the rich and famous.

On the contrary, as the pair and their colleagues embark on gruelling tours round pubs, clubs, boxing gyms, book-signing sessions and occasional black-tie dinners, Buchanan and Mcinnes are never really sure whether they are on the verge of a windfall or a catastrophe.

Mr Mcinnes said: “I don’t have hundreds of photos of me and Ken together, but what I do have are thousands of happy memories.

“But, for all the time I have been honoured to know Ken, I thought he had one fault, his generosity. He could never ever say no. If he had a pound in his pocket, you would get 50p of it and he would even give you the shirt off his back.

“Yes, he enjoyed a wee drink, but people forgot he gave up his youth and teenage years to dedicate himself to his dream of becoming the world champion and while not many people can say they achieved their dream in life, Ken did.

“He is a very proud man, and especially when he talks about his family. He would always stand tall and tell anybody who would listen it was his dad, Tommy, who made him the boxing legend that he eventually became.

“We must always remember it is memories that are the real trophies in life, not possessions.

“I am lucky, I have lots of good memories of the man, but Ken will be remembered more when he is no longer with us.

“When the time comes, a lot of celebrities will all want to be seen and they will all talk highly of Ken, as they should.

“But where were they when Ken was in hospital? As somebody wrote in a previous interview: ‘If Edinburgh doesn’t want him, New York will take him and cherish him’.”

It’s a bleak conclusion from Mcinnes who was himself a talented boxer for St Francis ABC in Dundee, fought for many Midland district teams, and competed for his regiment during his decades in the Black Watch, as well as serving his country in and out of the ring.

But he’s right to focus on the two distinct strands in his confrere’s career: the plaudits-strewn chapter when Buchanan was in his pomp – and how things unravelled after retirement.

Care home woes are beyond our Ken in the Covid-19 era

Ken Buchanan has experienced plenty of tough challenges in his lifetime.

But, as Jock Mcinnes will testify, he has never been floored by any opponent – until Covid-19 arrived.

A few months ago, he received the message that his friend had taken to going out on his own and wandering the streets and gradually forgetting where he was.

The decision was taken to put him under medical care at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary.

But, as his confusion increased and it became obvious he was prone to hallucinations, he was moved into a local care home in Leith, which offers nursing and nursing medical care for those who are living with dementia.

Mr Mcinnes tries to visit him at least once a fortnight, although the current slew of restrictions make this a difficult pledge to keep.

As he said: “On Wednesday August 19, I got up at 7.30 and headed off to see Ken.

“I was a wee bit early arriving, so I sat outside reading a newspaper. Then, five minutes later, a care worker came out and said: ‘Ken is having a coffee and is ready for you now’.

“I was dressed in PPE, then took a seat in the garden under a gazebo and out popped the man. ‘Hi Jock,’ he said.

“At least he had recognised me.

“Then we sat down and caught up on life. During our chat, I asked him if he wouldn’t mind signing a glove for me. It was for a big fan up in Aberdeenshire, by the name of John Boyce.

“John actually travels to Manila to stay over and have (the only eight-division world champion in the history of boxing) Manny Pacquiao sign stuff for him.

“Straight away, Ken went into a Victor Meldrew impersonation, saying, ‘I don’t believe it’. Then he added: ‘Aye, no bother pal, it wouldn’t be a visit without you getting a couple of signatures’ and laughed to himself.

“During the visit, Ken said he was cold, so one of the carers put a wee blanket around him. The time had flown. However, I had already asked to come back for another visit and the senior career told me that would be fine.

“Ken gave me a fist pump to say goodbye. Normally, it would have been a big bear hug.

“But, as Bob Dylan said: ‘The times, they are a-changing’.”

Life was golden in the ring

There were some people who thought he might not be around to celebrate his 75th birthday, but Ken Buchanan has always been a resilient character, in and out of the boxing ring.

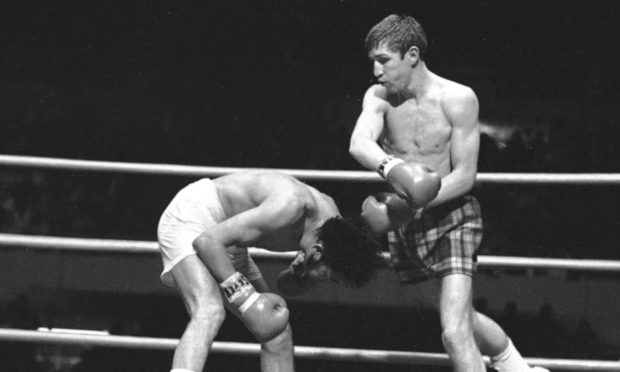

Five decades may have passed since the wiry, indefatigable competitor travelled to Puerto Rico, where he defeated Ismael Laguna, the world lightweight champion from Panama.

Yet although many experts believed San Juan’s warm weather would affect Buchanan, he always believed in his own abilities once the bell had tolled and beat Laguna in a brutal battle of wills to become the king of the world.

It was the crowning moment of a pugilistic career which began on a summer’s afternoon in 1953 when his father, Tommy, took him to see the Joe Louis Story at an Edinburgh cinema.

At eight years old and a mere three stone and two pounds, the kid was soon entreating his dad to buy him a pair of boxing gloves and his ceaseless cajoling eventually paid dividends.

He told me: “I would badger him and pester him, but he kept stalling, so I had to use a different strategy.

“I waited until one of his pals was talking to him in the garden, then I dashed up to him and shouted: ‘Dad, dad, are you going to teach me how to box?’

“He looked at me with irritation, and replied: ‘Aye, but just wait a while’.

“I answered back immediately: ‘No, no, you have to promise’, and out of sheer exasperation, he said: ‘Okay, I promise’ in front of another person.

“So that was me settled, and we went down to the Sparta Club in the next couple of days. I loved it, you know. Sure, I was a dunce at school, but once I had slipped the gloves on, I was an equal for anybody.”

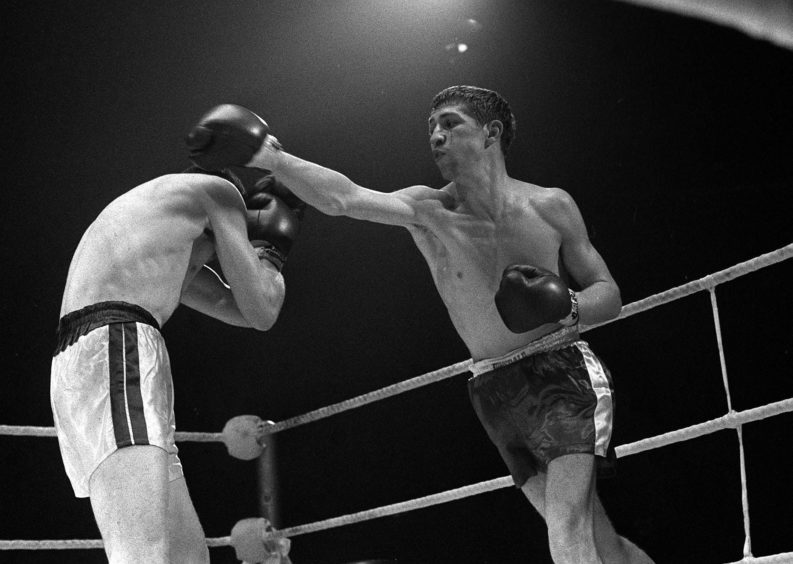

That much was unarguable during a halcyon period from 1970-75 when nothing, be it partisan officials, riotous foreign fans or dishonest antagonists, could prevent Buchanan from feasting on a rich diet of honours and baubles.

Whether overcoming midday temperatures in excess of 100 degrees to best Laguna, or trouncing Ruben Navarro in Los Angeles five months later, there was an unstinting dedication in his disposal of rivals such as Donato Paduano, Mando Ramos and Carlos Hernandez.

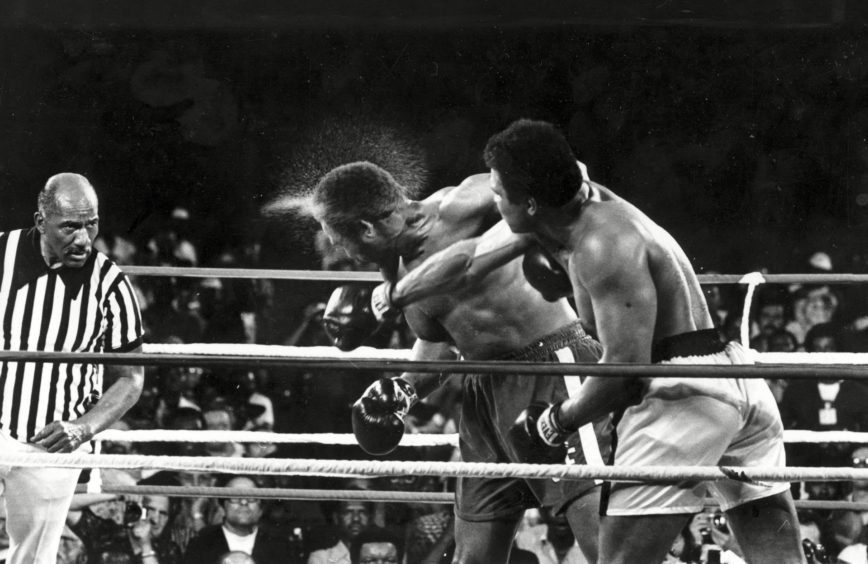

That was in the build-up to one of the most famous and notorious tussles in fistic history at Madison Square Garden, where Buchanan, pitted against the Panamanian Roberto Duran, nicknamed The Hands Of Stone, competed so perseveringly and courageously that the South American eventually rammed his knee into the groin of his adversary, leaving him unable to continue amid bedlam from all quarters.

To many of the throng, it was a blatant transgression, but Buchanan has grown accustomed to dealing with life’s slings and arrows and occasional low blows.

He added: “Ach, it’s a hell of a long time ago now, but it still hurts. It had been bloody hard graft seizing the world championship from Laguna in San Juan and holding on to it for two years, because don’t forget this was at a stage when any one of half-a-dozen guys would have been good enough to win a world title today.

“But, on the other hand, there were great times and a stack of tremendous stories to put next to the disappointments.

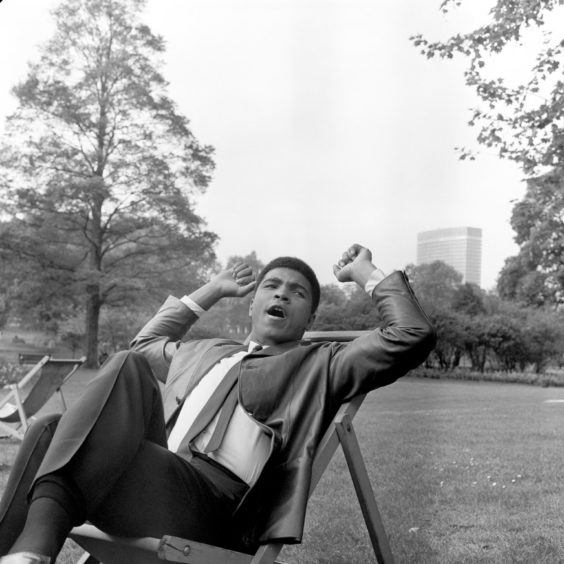

“I mean, there was one occasion when I met Muhammad Ali in New York in 1970, and we shared a room together before the fight. You know how? Well, whilst we were at the weigh-in, Angelo Dundee came up to me and said: ‘Ken, is it okay if Ali shares your dressing-room?’

“Think about it. Here was me, this wee laddie from Dalkeith, and I’m getting asked for a favour by the trainer of the greatest fighter who has ever lived.

“I said to Dundee: ‘You’re only kidding, right?’ But no, he was deadly serious, and Ali and I swapped banter and jokes and warmed up together prior to our contests.

“Memories are made of these moments.

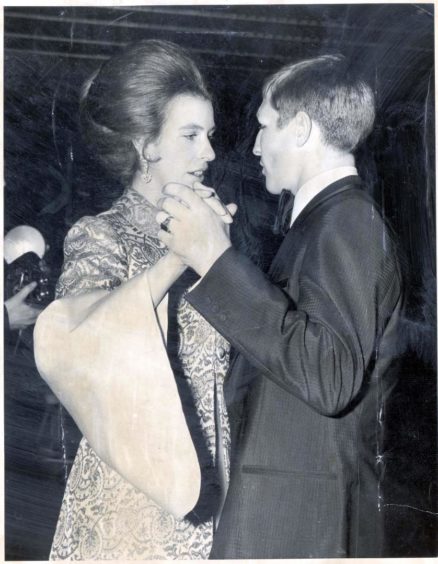

“There was also one night in 1971 when I was named the British Sportsman of the Year – Princess Anne collected the women’s award – and the pair of us had to dance together.

“Anyhow, I’d gone to lessons for three months – my dad was a terrific dancer – and I thought I would be a natural, but I wasn’t. In fact, I was more nervous than I had ever been before walking on to the floor.

“But, like a fool, I found myself telling the princess: ‘Don’t worry, hen, dancing is in my blood’. Well, after a couple of minutes shuffling around with not a shred of co-ordination, she spoke through clenched teeth: ‘You must have a circulation problem then because it hasn’t reached your feet’.”

In these balmy yesterdays, cash was flowing into Buchanan’s coffers and vanishing with equal speed. His buddies, the kind of shysters who would steal the ornaments off their granny’s mantelpiece, slapped him on the back and supped deep on his largesse and naivete.

On and on it rolled, this giddy gravy train, until the inevitable decline commenced. Buchanan lost a fraction of his sharpness and gradually, inexorably, his lustre vanished along with his supposed drinking acquaintances.

He once told me, with a quiet twinge of regret: “There’s no question about it, if I could change things, I would do so, but there’s no use dwelling on what might have been.

“By the end of the 1970s, the papers regularly carried pieces claiming that I was a washed-up has-been, down on my luck, and I reached the point where I would tell the journalists: ‘Ach, write what you want. If you believe I’m a down-and-out, stick it all down’.

“At least I didn’t wind up like Ali. I’d heard stories that his illness was really bad, but when I watched this giant of a man reduced to shambling into the Waterstones shop (in Edinburgh in the early 1990s) with no idea where he was, it was more than I could stand.

“I had to leave the store and dash away because I was greetin’ my eyes out at the state he was in. It dragged me back to that scrap he had with George Foreman (in 1974), where he took punch after punch on the ropes.

“It was the sort of fight the authorities shouldn’t have permitted to continue – and was pummelled beyond any reasonable bounds. (Even though Ali finally triumphed).

“He was a human punch bag and it must have taken its toll. He was a magnificent boxer and a marvellous personality, but he was just human like the rest of us.

“I’m just glad I had the opportunity to meet him and become friends with him when he was one of the coolest people on the planet.”