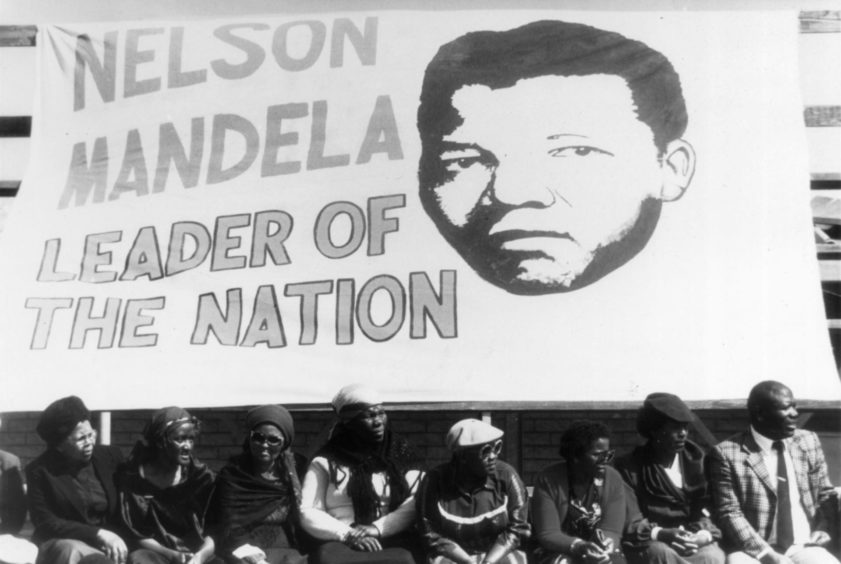

It was the historic night Dundee took a stand against apartheid and voted to give Nelson Mandela the keys to the city.

The move to bestow the Freedom of Dundee to Mandela 35 years ago on October 31 1985 was not without controversy and went through 29 votes to 13 while he languished in a cell in Pollsmoor Prison in South Africa.

While many saw Mandela as a freedom fighter, others felt he was a terrorist.

Glasgow was the first in the world to make him a freeman in 1981 and Dundee soon followed.

Petition

Labour group leader Ken Fagan moved that the freedom be granted to Mandela after 4,000 people in Dundee signed a petition which was backed by anti-apartheid protest rallies in the city.

The tide of support for Mandela helped convince Fagan to make the move and he said “there was no more distinguished person in the world than Mandela, who had become a symbol of hope and strength”.

Lord Provost Tom Mitchell said giving the freedom would help the council and Dundee people to better understand what was going on in South Africa where the white-ruled regime was an international pariah.

On a night of drama there were so many people who turned up to the meeting that hundreds were left outside and the vote went ahead against the backdrop of chanting and singing.

The historic summit saw Conservative councillor Andrew Lyall vote with Labour in favour of the award and immediately resign from the party after defying Tory standing orders while David Coutts from the SNP abstained after it emerged that 80% of his Hilltown constituents were opposed to the move.

The freedom was eventually granted “in recognition of his long years of imprisonment as a result of his fighting for freedom from apartheid for his fellow black citizens of South Africa; of the symbol which he has become throughout the world in the campaign to change the South African Government’s repressive and racist policies; and in testimony of the esteem in which he is held by the councillors and citizens”.

Central Library

Dundee also marked Mandela’s fight to free his fellow countrymen from apartheid with a plaque unveiled in 1997, in the Central Library.

Dr Matt Graham, senior lecturer in History at Dundee University, said the city played a key role in Scotland’s anti-apartheid movement.

“In the 1960s people would have heard of Mandela because he was a leading anti-apartheid leader put on trial and sent to prison,” he said.

“But his name disappeared from the media and from the public consciousness throughout the 1960s and for much of the 1970s.

“The anti-apartheid movement then started to grow and in Scotland the Scottish Committee of the Anti-Apartheid Movement (SAAM) formed in 1976 and the first meeting actually took place at Dundee University Students Union.

“The mid-1970s was the time that Dundonians therefore would have been getting a greater sense of the anti-apartheid struggle and the brutality of things which were happening in South Africa.

“This coincided with the Soweto Uprising where students were shot by the apartheid police which prompted international condemnation.

“Dundee as a city has quite a radical tradition and Dundonians have a long history of identifying or at least affiliating with causes around the world such as the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War.

“In the late 1970s and early 1980s that’s when things started to pick up for the AAM.

“The British Anti-Apartheid Movement took Mandela under its wing as their ‘cause celebre’ and that was when the crusade began to snowball, making him an important figure in the struggle against apartheid.”

Decisive stand

Dr Graham said Glasgow conferring Mandela the freedom of the city in 1981 was remarkable and evidence of “Scotland taking a decisive stand against apartheid”.

He said: “Labour councillors in Glasgow and then Dundee really pushed this with the support of the AAM, the trade union movement and also some of the religious movements in Dundee as well.

“Apartheid was immoral and brutal and like-minded people decided to take a stand against this.

“I think this is something that Dundee should be very proud of.

“It was also part of an effort to rid racism and prejudice from Dundee itself.

“As a city we are still tackling these issues, but at the time, it was an opportunity to say: ‘Yes it might be an issue 6,000 miles away but by standing up against apartheid we also help change ourselves here in Dundee too’.

“The ANC and Mandela definitely split opinion. We must remember this was the time of Margaret Thatcher and a Conservative Government which openly supported the apartheid state, while the broader right-wing media were stridently against the ANC.

“A lot of people retrospectively will bask in the Mandela legacy and talk about what a wonderful person he was.

“Dundee actually did something when others didn’t.

“So Dundee has a lot to be proud of for taking that stance and making that choice.

“It shows that making a hard choice can often be the right one and by doing so it means that Dundee can look back proudly.”

Dr Graham is an expert on the topic and has put together with Dr Chris Fevre an exhibition on the anti-apartheid movement which will be staged soon and will explore Dundee’s connections to Mandela which is entitled Scotland, Global Solidarity and Mandela.

Over his 27 years of imprisonment, Mandela became the world’s best-known political prisoner.

Simple Minds

The efforts to free Mandela became mainstream with global pop stars such as Jim Kerr, from Glasgow band Simple Minds, writing songs and playing concerts in support of his freedom.

International pressure, in the form of sanctions against the South African regime, eventually led to Mandela’s release in 1990 at the age of 71.

In October 1993, Mandela received the freedom of nine cities, districts and boroughs in a special ceremony at Glasgow City Chambers, including the freedom of the City of Dundee which he acknowledged with his signature.

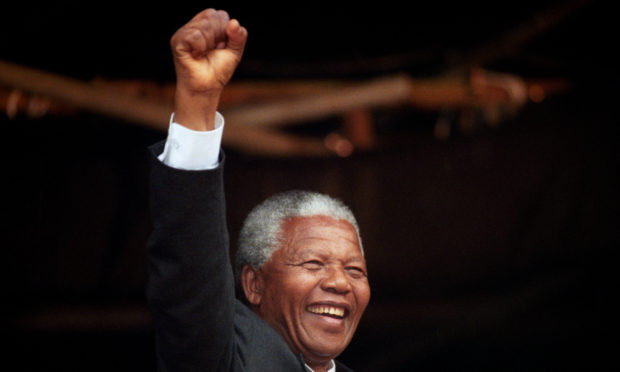

The event famously saw Mandela dancing on stage in George Square, to the delight of the crowd of 10,000 people who had come to see him.

He said: “Whilst we were physically denied our freedom in the country of our birth, a city, 6,000 miles away, and as renowned as Glasgow, refused to accept the legitimacy of the apartheid system and declared us to be free, you, the people of Glasgow, pledged that you would not relax until I was free to receive this honour in person.

“I am deeply grateful to you and the anti-apartheid movement in Scotland for all your efforts to this end.”

A year later Mandela was elected South Africa’s president.

He retired from politics in 1999, but remained a global advocate for peace and social justice.

Mandela returned to Glasgow in 2002, when he attended a press conference with Abdelbaset Al-Megrahi, the convicted Lockerbie bomber, at Barlinnie Prison.

He died in December 2013.

Freedom of Dundee through the decades

The Freedom of Dundee is an honorary title bestowed upon select individuals, who are given the title of “Burgess”.

Historically, the freedom of the city would grant holders of the title the right to vote, and gave honoured military units permission to march into the city with “drums beating, colours flying and bayonets fixed”.

Chief among those who received the Freedom of Dundee in the past were politicians.

They included Sir John Leng, MP for Dundee and founder of the Evening Telegraph, who was awarded the freedom of the city in 1902.

Dundee MP Thomas Johnston received the honour in 1947.

The roll also includes several past prime ministers. Herbert Henry Asquith received the honour in October 1912, while he was prime minister and MP for East Fife.

Other prime ministers given the honour included James Ramsay MacDonald and Stanley Baldwin, while the Queen Mother and the Black Watch were recognised in 1954.

American ambassador to the UK, Whitelaw Reid, became a Burgess in 1906 for, among other reasons, “testimony of the high regard entertained by the citizens of Dundee for the American people”.

Emma Grace Marryat, the half-sister of James Caird, was awarded the freedom of the city in 1918 for the gifts of the Caird Hall, Caird Park and Belmont Estate.

Other recipients include one-time Lord Provost Maurice McManus, who was given the title in 1981, Dundee Parish Church minister William Macmillan and former Dundee United manager and chairman Jim McLean.