Forgotten memories from three Black Watch soldiers have captured the excitement felt when the guns fell silent on the battlefield in 1918.

The fighting had defied expectations and the correspondence reveals how each of the men got the news of the German surrender which marked the final day of the four-year conflict.

The regiment raised 25 battalions during the course of World War One and mainly fought in France and Flanders.

By the time of the Armistice in November, 8,000 members of the regiment had lost their lives.

Ian Shepherd

Major Ian Watson Wardlaw Shepherd was born on January 8 1893 at Tayview in East Newport, Fife.

His parents were John Watson Shepherd, a jute merchant, and Margaret Annan Scott MacKay.

He was one of three children and the electoral register for Fife in 1914-15 listed Shepherd’s profession as clerk.

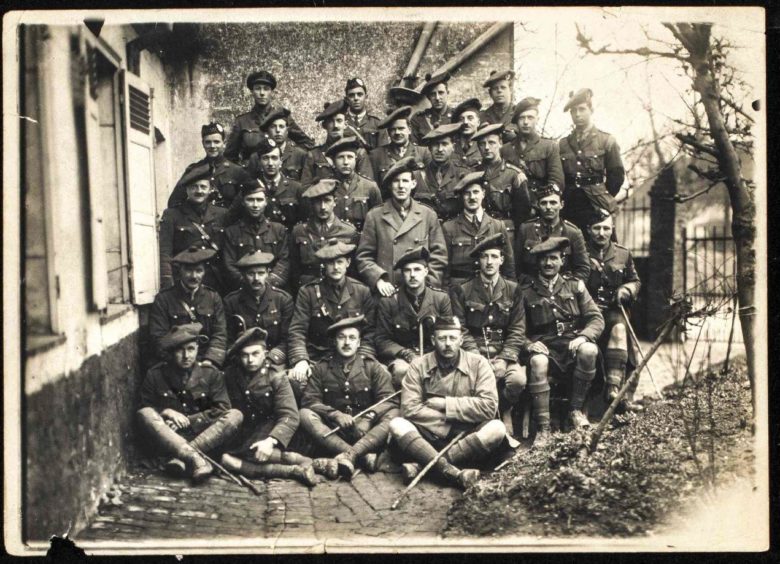

With the outbreak of war, aged 21, he joined the 4th Black Watch in August 1914 as a 2nd Lieutenant.

From May 1915 to February 1916 he was Staff Captain for the Black Watch Territorial Brigade.

He then moved to the 4th Black Watch Reserve Battalion until October 1916 when he left with the 8th Black Watch to serve abroad.

By January 1918 he was promoted to Major and his entry in the 8th Battalion diary provided an insight into what life was like for those on the frontline in Flanders when the Armistice halted the fighting.

“After a few days training the Battalion marched back on 10th November to billets in Harlebeke, where news of the acceptance by Germany of the Armistice terms were received about 7pm,” he said.

“Troops and civilians thronged the streets of Harlebeke and all the bands of the brigade paraded and played until nearly midnight.

“On November 11th, word was received that the Armistice was to take effect from 11am, and the day was observed as a holiday.

“The next few days were without incident; parades were held at intervals and some training was carried out.

“On the 13th, Lieutenant Farmer and the Battalion Padre proceeded to Meteren to put up crosses on the graves of men who were killed in the taking of that village on July 19th.”

Major Shepherd returned from war and married Lucy Ehler in 1920 in Marylebone, Middlesex.

He died aged 60 on January 24 1953 in Hampshire.

Archibald Duke

Captain Archibald Whyte Duke was born in 1892 in Brechin to parents David Duke and Jane Anne Duke.

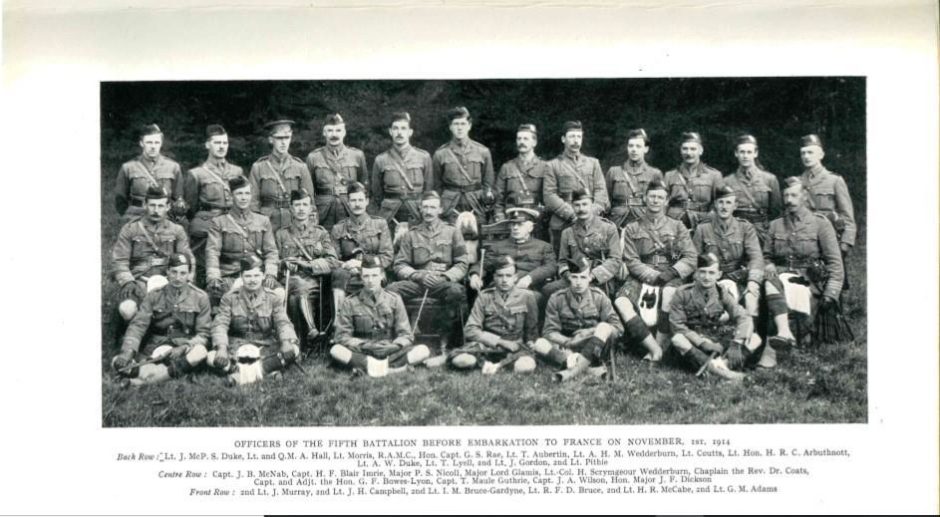

He was commissioned into the 5th (Angus and Dundee) Battalion, The Black Watch, as a 2nd Lieutenant on December 28 1911 and was promoted to Lieutenant on June 28 1913.

Stuart Kennedy, curator at The Black Watch Museum in Perth, said: “While serving in the First World War, Archibald spent most of his military career in France with the 5th Battalion but transferred to other battalions and regiments on several occasions.

“Between January 1915 and February 1916 he spent time periodically with the Machine Gun Corps, 154th Company.

“After falling off a horse and injuring his knee on February 23 1916, Archibald spent a few weeks at ‘Princess Henry of Battenberg Hospital’ in London and joined the 3/5 Battalion, The Black Watch, in April 1916 where he was based at North Camp, Ripon, England.

“Around the end of May 1916, Archibald was attached with the 12th Labour Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, and spent eight months providing manpower to unload British ships at docks and move timber in forests near Rouen, France.

“It was during this time that he was promoted to Captain on June 1 1916.”

After service leave in the UK in January 1917, he transferred to command No. 66 Prisoners of War Company for 14 months in camps near Le Havre, France, and then served as Deputy Assistant Director Railway Traffic for a short period of time.

He was transferred back to the Prisoners of War Company where he commanded No. 69 until the end of the First World War.

Le Havre

On November 12 1918 he wrote a letter to his mother from Le Havre and told her how “things have moved with extraordinary suddenness these past few days and now the war is more or less over”.

He said: “It really seems too good to be true, we got the news yesterday about one o’clock that the Germans had signed the Armistice terms and there were great rejoicings all round.

“All the boats on the river blew their sirens as soon as they got the news and continued more or less all afternoon and also firing blank charges from their guns.

“There was a greater number of boats going up and down than usual and all were decorated.

“The Norwegians and Swedish boats made as much noise as any.”

In December 1918, he re-joined the 4/5 Battalion, The Black Watch, and returned home to Brechin in January 1919.

After his military career, he became a manufacturer.

He married Anne Balmanno Leishman, daughter of Dr and Mrs Arthur Leishman in September 1921, and died at his home on September 10 1956 aged 63.

John Stewart

Lieutenant Colonel John Stewart was born on May 21 1869 in Edinburgh to parents John Leveson Douglas Stewart and Margaret Anne Thomson.

He married Valentia Worship on March 3 1892 in Norfolk and they had two children, Amy Mary Hamilton Stewart and Keith Ian Douglas Stewart.

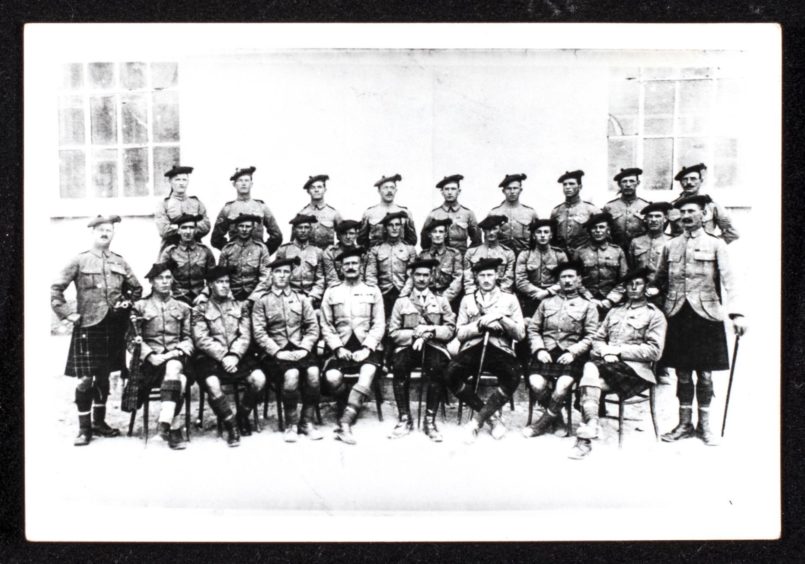

Lt Col Stewart initially served as Captain of the Ceylon Planters’ Rifle Corps, serving in the Boer War, South Africa.

On returning from duty, he resigned from the Volunteers.

Despite not meeting the conditions for appointment, he then became a Captain in the Royal Garrison Regiment.

He joined the Black Watch on February 14 1906 and was soon seconded as Adjutant of the Militia Battalion (later 3rd Battalion) of the Highland Light Infantry.

The depot was at Hamilton.

He retired before the outbreak of the First World War, but on mobilisation he joined the 9th Battalion as Second-in Command.

The 9th Battalion left for France on July 8 1915, joining the 15th Scottish Division.

This included action at the Battles of Loos.

He was sent home in October 1915 for an operation, returning in January 1916 to France.

Again he was sent on sick leave in June 1916.

After six months of leave, he returned to service on December 26 1916 travelling to Mesopotamia.

In 1917 he was made Lt Col and commanded the 2nd Battalion in Mesopotamia.

At the end of October his unit moved on and was in Tripoli for November and the Armistice.

Rather erratic

He wrote a letter to his wife the day after and told her “we are at last on the way towards peace”.

“The news reached us last night just before dinner and immediately every unit began letting of some old thing or other,” he said.

“The gunners fired a salute of 51 guns but towards the end, having been served out with a lot of rum during the performance – they got rather erratic and I believe fired a good many more than that number.

“The trench mortar people fired a salvo of trench mortar bombs, the Punjabis tom-tom band turned up, my pipers played “After the Battle” and as you can imagine things were fairly lively for about twenty minutes.

“To add to the row on land three steamers and a hospital ship in the harbour blew their sirens…

“Well old girl it’s been a long long war and I thank God as I am sure you do that I have been spared through it all…”

Lt Col Stewart was awarded the Distinguished Service Order on June 3 1919.

He wrote a short history of the 42nd Regiment and later co-wrote a history of the 15th Division with Perth-born Thirty-Nine Steps author John Buchan.

He also published a Medal Roll of The Black Watch from 1801 to 1911.

In his later years, Lt Col Stewart was President of the London Branch of The Black Watch Association.

Aged 61, Lt Col Stewart died on February 19 1931 in Colchester, England.

Lt Col Stewart stipulated that his personal memoirs could only be opened in 2014 which was most likely due to his desire to protect the personal lives of himself and his family.