There’s a famous old show business adage which insists that you should never work with children or animals.

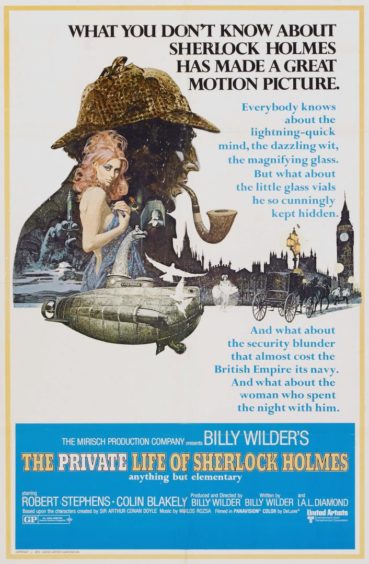

And we should probably add monsters to that list, on the basis of what happened when the revered Hollywood director Billy Wilder arrived in the north of Scotland to shoot scenes for The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes 50 years ago.

He and his colleagues visited a variety of locations, including Urquhart Castle, Nairn railway station, the Drumnadrochit Hotel, Castle Stuart, Kilmartin Hall on Loch Meiklie, Eilean Donan Castle, and in and around Loch Ness.

Problems

Yet, despite this hectic whirl of activity, the project was plagued by problems which not only left a large-scale model monster in the depths for nearly half a century, but led to studio executives taking a pair of shears to the finished work.

Wilder had previously been responsible for a plethora of classic films, including Double Indemnity, The Lost Weekend, Sunset Boulevard, The Seven Year Itch and The Apartment.

When the latter swept the board at the Academy Awards in 1961, he became the first individual to walk away with three of the most prestigious honours: Best Director, Best Original Screenplay (with his regular co-writer IAL Diamond) and Best Picture.

He was, in his prime, an individual blessed with a remarkable imagination, energy and irrepressible attitude who had escaped from the Nazis in the early 1930s and turned up in Hollywood as a penniless refugee. He was also a devotee of Holmes and the stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, which he had long dreamed of bringing to the silver screen.

So the venture couldn’t fail, could it? And yet, although Wilder devoted more than a decade to creating what he hoped would be another masterpiece, the movie sunk like the monster.

As author Jonathan Coe, who has written a new book Mr Wilder & Me, said: “He took over Pinewood for six months, spent more than $10million, and then it flopped big time.

“The studio made him cut it down by almost an hour before they would even release it.

“In the last few years, the Beatles had arrived, the Summer of Love had happened, and Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider had changed American cinema.

“Suddenly, the Wilder/Diamond classical approach to film-making looked fusty and dated.”

The problems weren’t confined to any particular area.

Determined to move away from the template of the master sleuth, as depicted by Basil Rathbone in a series of 1930s/40s films where he excelled as the Baker Street brains trust, accompanied by Nigel Bruce as a loyal, but perennially bumbling Dr Watson, Wilder struggled to cast the new venture.

Unconvinced

He initially chose Peter O’Toole in the lead role with (the future Inspector Clouseau) Peter Sellers as Sherlock’s companion, but that notion soon fell through. Rex Harrison – of My Fair Lady fame – was briefly in the frame, yet Wilder was unconvinced.

Finally, he chose Robert Stephens – a classically-trained actor, who was at the time married to Dame Maggie Smith of Miss Jean Brodie and Downton Abbey renown – and Colin Blakely as Watson, with Christopher Lee filling the role of Sherlock Holmes’ brother, Mycroft, despite bearing no resemblance to the character in the books.

The purists were – and still are – shocked at these developments. Jon Lellenberg of the Conan Doyle Estate told me this week: “The movie’s Watson, played marvellously by Colin, was not the ‘boobus Brittanicus’ that Nigel Bruce had been.

“But that’s about it, as far as I am concerned, and from the day that I saw it in 1970, I wish I had saved my money.

“Robert Stephens was an unsatisfactory Sherlock Holmes, too soft around the edges, and I insufficiently cerebral. And Christopher Lee, an admirable actor, was all wrong for Mycroft if you care about the (stories in the) canon.

“The Russian ballet business (which delves into Holmes’ sexuality at the start of the film) was Billy Wilder at his misjudgmental worst. The submarine as Loch Ness Monster plot wasn’t quite as distasteful, but it was maybe even sillier.”

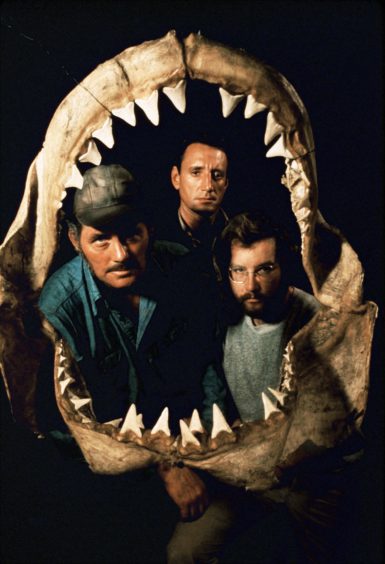

Wilder wasn’t the only director who struggled with working on water.

Steven Spielberg toiled with his misfiring mechanical sharks in Jaws to the stage where he had to rely more on the power of suggestion, sharp editing and small glimpses of the marine villain – which actually improved the classic film until Robert Shaw became a smorgasbord at the climax.

Then there was Kevin Costner’s ruinously expensive vanity project Waterworld in 1995. And Lew Grade’s soggy fiasco Raise the Titanic in 1979, of which he concluded: “It would have been cheaper to lower the Atlantic.”

When Wilder and his production team pitched up in the Highlands, they brought with them a giant 30-foot model of Nessie, designed by special effects artist, Wally Veevers, whose other work included 2001: A Space Odyssey, Superman and Local Hero.

Disappeared

But, despite strenuous efforts to make it convincing, and even allowing for the plot which stressed the monster was only being used to cover up the development of a new pre-First World War submarine by the Royal Navy, Veevers’ creation posed one problem after another – until finally, it disappeared under the waves while being towed to its destination.

Alec Mills was a camera operator on the second unit of the film and his son, Simon, told the Press and Journal about the travails faced by the film-makers with their rogue prop.

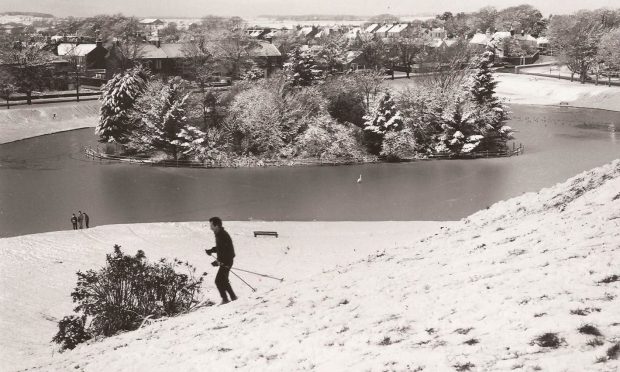

He said: “I have worked on several documentaries about the Loch Ness Monster and, whenever I visit Drumnadrochit, I always think about the summer of 1969.

“Alec was not long back from Portugal where he had been filming (the James Bond movie) On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and, although I was only nine years old, I recall him telling me a few things about the ‘monster’ before it sank.

“Billy Wilder didn’t like the monster’s two humps and asked Wally Veevers to remove them, but unfortunately, the humps also contained hidden buoyancy aids and when it was towed out into the loch – by a Vickers submarine – it quickly rolled over and was gone.

“Alec’s involvement was more on the camera side than in the field of special effects, but I remember him saying they had filmed the ‘monster’ a few times prior to it sinking and that, through the camera viewfinder, it looked pretty unconvincing.

“In fact, it looked so awful that they were reduced to largely filming it through foreground grass or branches, just to break up the image, so it would look a bit better on camera.

“I suppose you could say that the sinking was quite fortuitous in these circumstances. Because, after it happened, the monster in the loch sequence was later filmed in one of the big tanks at Pinewood Studios.

“It’s a long time ago, but the film was one of my childhood favourites.”

When it was eventually released – after being trimmed by more than an hour – at the start of December 1970, some critics were not as slow as Inspector Lestrade in panning Wilder’s work.

Roger Ebert wrote that it “was disappointingly lacking in bite and sophistication”, while Gene Siskel called it “a conventional and not very well written mystery.”

The Los Angeles Times added: “The whole effect of the picture is a kind of affable blandness which, given the expectations you have of Billy Wilder, constitutes a disappointment.”

Empire review

Some reviewers were more positive with Empire magazine describing it as “the best Sherlock Holmes ever made” and “sorely underrated in the Wilder canon.”

And Mark Gatiss, one of the men behind the smash-hit TV series Sherlock, featuring Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman, went further in claiming it was “the film that changed his life….the relationship between Holmes and Watson is treated beautifully.”

Whether or not the venture should be regarded as a horror story or a DVD bonus on Wilder’s formidable CV will continue to be discussed by experts on both sides.

But there was no denying the global attention which surrounded the discovery of the lost Nessie model in 2016, a little matter of 47 years after it disappeared into the depths.

The item was located 180 metres down on the lochbed by Munin, an underwater robot which had previously been used to search for downed planes by Norwegian company Kongsberg.

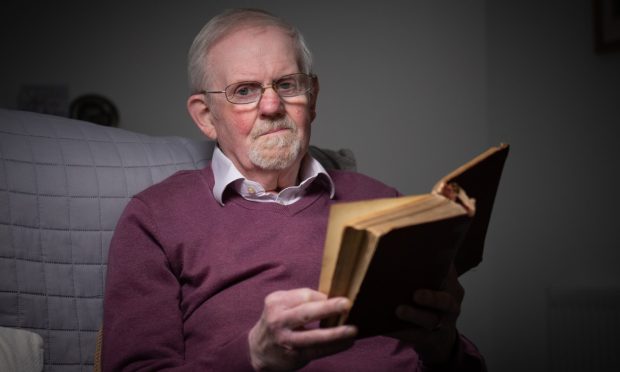

The unusual find prompted mass media coverage and Adrian Shine, a driving force of the Loch Ness Project recalled this week how it had reopened interest and intrigue in the famous stretch of water.

He said: “The Norwegian company, Kongsberg Maritime, had been testing underwater equipment in Loch Ness for 40 years.

“Whenever possible, they assisted the Drumnadrochit-based Loch Ness Project with research, most recently, with Operation Groundtruth.

“This is an ongoing programme, begun in 2001, which aims to discover and notify objects of historical interest lying on the loch bed. In January 2016, a claim was made concerning the discovery of a 270m depth, close to the shore in the loch’s northern basin.

“However, on the strength of approaches by documentary production companies wishing to see ‘Nessie’s Lair’ investigated, it became possible to bring Munin, one of Kongsberg’s Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) to the loch.

“Munin was one of the ravens perched on the shoulders of the one-eyed Norse god Odin, which would fly away and return with news from around the world.

“So it is simply launched into the water, submerges without a tether, carries out its mission and then returns to the surface where sonar maps and other results are downloaded.

“Because Munin can ‘fly’ so close to the loch bed, the fan of narrow beams from its sonar is very tight leading to very high resolution of objects and topography.

“The Kongsberg team, led by Craig Wallace, dispatched Munin as planned and as expected, found no exceptional depths.

“That was no surprise, but we had discreetly taken the opportunity to route Munin over the expected position of something we had been seeking for a long time.

“The results finally and unmistakably revealed that we had located the Loch Ness Monster from the film The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.

“There was almost as much fuss in the next few days as if we had discovered the real thing.”

As a youngster in Vienna, Wilder had interviewed Richard Strauss and Sigmund Freud on the same day. When he died in 2002, aged 95, the obituaries recounted how his mother had called him Billy after Buffalo Bill Cody, whose Wild West shows she had once seen in New York.

He aimed high and missed the target with The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.

But it’s a measure of his genius that, even now, people still remember and talk about his duel with literature’s most famous detective and his date with Drumnadrochit.

The best and worst of Holmes on the silver screen

The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939): The first and best of the 14 films starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce as Holmes and Watson, this was an atmospheric and genuinely suspenseful adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle’s classic novel.

And it helped that Rathbone might have stepped straight from the pages of the book. The producers even managed to insert a reference to Holmes’ drug habit – He says: “Quick Watson, the needle!”, at the conclusion – without attracting the wrath of the censors.

A Study in Terror (1965): It divided the critics, but an excellent cast, headed by John Neville as Holmes, assisted by the likes of Robert Morley, Frank Finlay, Donald Houston, Barbara Windsor and Judi Dench, breathed life into this original script about Holmes tracking down Jack the Ripper.

The New York Times critiqued: “The entire cast, directors and writers do their roles well enough to make wholesale slaughter a pleasant diversion.”

Mr Holmes (2015): A poignant tale about the detective, set during his retirement in Sussex, the film follows a 93-year-old Holmes, played with genuine pathos by Sir Ian McKellen, who struggles to recall the details of his final case because his mind is slowly deteriorating.

The chemistry between Holmes and his widowed housekeeper Mrs Munro – played by Laura Linney – is truly affecting and both actors gained accolades for their performances.

Holmes and Watson (2018): This could be described as the perfect Christmas film, but only because it’s a giant turkey which left critics and audiences stuffed.

Despite an impressive cast, including Will Ferrell, John C Reilly, Ralph Fiennes, Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon, the dire script and bad slapstick scenes ensured it was a box-office bomb, with many reports of people walking out early during screenings.

Rolling Stone magazine said: “It is so painfully unfunny that we’re not sure it can legally be called a comedy.”